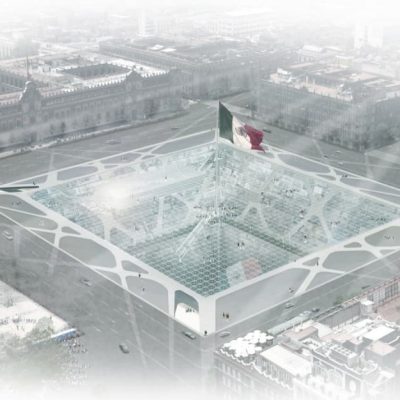

Mexico City is massive and famous for its urban sprawl, thanks in part to height restrictions forcing the city to grow out rather than up. There are also preservation considerations in play: no one wants to demolish historic old low-rise architecture downtown. In the face of these limitations, some designers have pitched unusual but provocative ways to densify the city without building skyscrapers. One such proposal calls for a 35-story subterranean groundscraper.

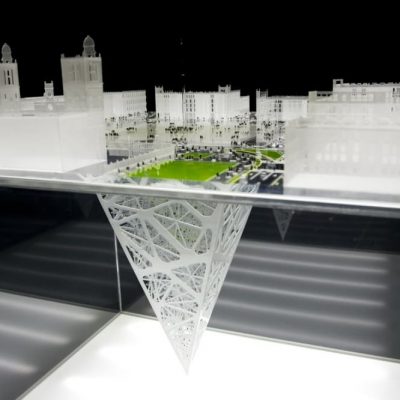

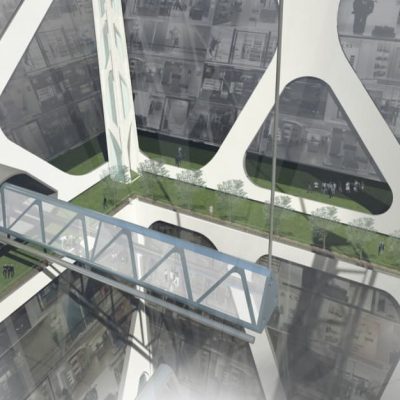

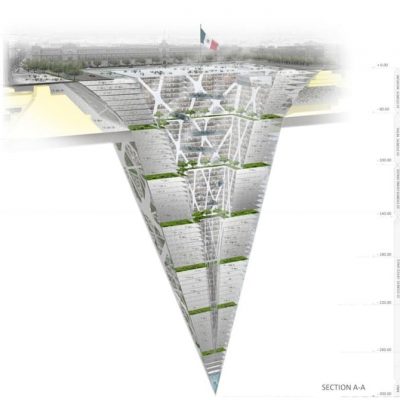

Designed by BKNR Architectura, this Earthscraper concept is quite compelling, at least on the surface. Situated in a prominent downtown plaza, the top of the structure serves as both a viewing platform for pedestrians and light well for building occupants below. Extending underground from that level, the rest of the structure would displace no public space nor historic architecture.

The inverted-pyramid shape helps take advantage of the soil’s natural angle of repose, making it easier to excavate the site and shore up the structure on the sides. Its subterranean location would also give the building greater stability in the face of earthquakes.

Still, as impressive as it is on paper, this proposal is unlikely to see the light of day anytime soon (if ever), in part due to the expense of excavating so far down. It is also difficult to break ground on big projects like these with unique construction challenges – building codes were not designed with pyramidal groundscrapers in mind.

In reality, large-scale underground architecture is rarely created from scratch. New subterranean programs are more typically the products of adaptive reuse, turning existing voids toward new purposes.

Of Mines & Missile Silos

Economics and politics are behind many of the world’s more extensive excavation projects, from resource mines to missile silos. When mines run dry and silos are abandoned, many of the resulting voids represent significant sunk costs but correspondingly stable frameworks. Some of these idle spaces are perfect candidates for the right kind of reuse.

Located in a vast mine 100 feet below the surface in Louisville, Kentucky, the Mega Underground Bike Park makes good use of its unusual location. Situated in a weather-proof subterranean space, the park naturally protects riders from wind, rain and temperature fluctuations; the mine hovers around 60 degrees all year long.

The park’s operators also take advantage of the tons of soil churned up by the original limestone miners, reworking it regularly into fresh trails, ramps and jumps. At 320,000 square feet, it is currently the largest indoor BMX bike park in the world. If this example seems less than “architectural,” consider a comparable space on the surface would require a huge big-box building shell to house the same activity.

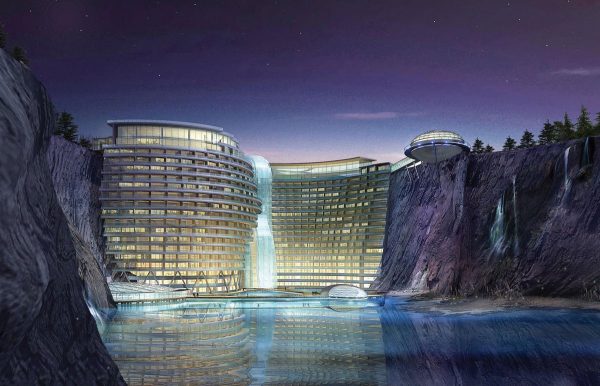

Open-pit mines lack the shelter of enclosed mines and offer different array of opportunities for architects and developers. Scheduled for completion next year, the Shimao Wonderland Intercontinental hotel in Shanghai will stretch 300 feet down into an abandoned quarry. The open-top space allows in natural light while rock formations provide scenic views for guests.

Nicknamed the “Groundscraper Hotel,” the design calls for a waterfall flowing from the surface level over a tall vertical atrium (a feature which may or may not survive value engineering). Incoming water pools in an artificial lake at the bottom of the pit. Geothermal energy from below will be tapped to power the hotel. Construction is well underway.

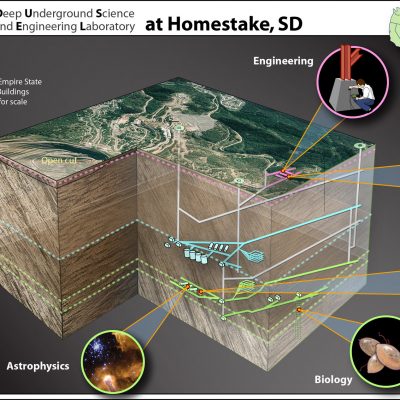

Other re-purposed mines support a broad spectrum of use categories, including entertainment, health, technology and science. A deep mine in Romania has been turned into a dazzling amusement park. In Ukraine, convalescing asthmatics take advantage of the air’s salinity in an old salt mine, using its tunnels as a wellness retreat. A limestone mine in Kansas hosts a naturally-secure and temperature-stable data center. A South Dakota scientific research laboratory used for dark matter experiments sits in a mile-deep gold mine.

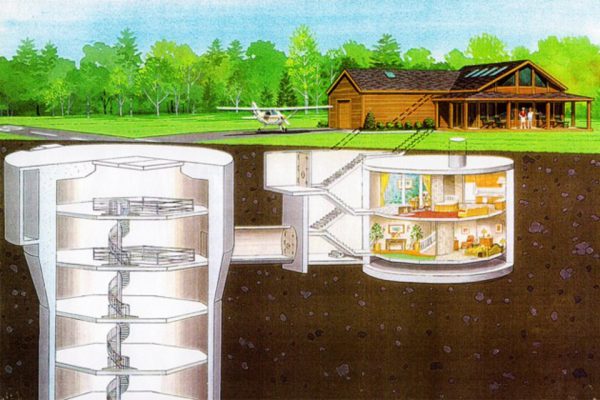

In contrast to vast and rough-hewn mines, missile silos tend to be well-defined spaces. Some are also already outfitted with underground levels made for human habitation (previously quarters for military personnel). Decommissioned silo complexes dot rural landscapes across the United States, thanks in part to nonproliferation policies.

Homes in silos are not for everyone, but survivalist-minded folks have gravitated toward them for decades. Their limited size, lack of light and vertical nature makes them unattractive to many potential occupants, but their reinforced shells and remote locations are appealing to some.

While constructed for durability, disused silos can face a number of issues, including mold and a lack of ready access to active gas, power, water and sewer lines. So while a silo and associated complex may come cheap, remodeling for habitation can be tough. Many silo buyers simply occupy auxiliary spaces and leave the primary silo zone alone.

Some ambitious entrepreneurs, however, have taken silo rehabilitation to the next level, converting vertical voids into multi-unit dwellings. These are sold as refuges in case of extreme disasters.

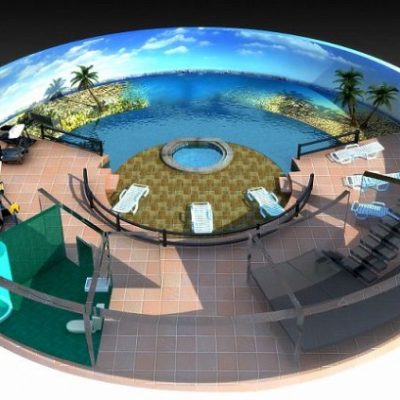

Luxury Survival Condo, for instance, covers the basics, including redundant infrastructure for power, water, air and food. It also boasts high-end amenities, including fitness facilities, climbing walls, dog parks and theaters. Survival silo locations are generally kept secret to avoid a rush on them during an emergency situation. Needless to say, they also cost millions and are thus only available to an eccentric elite.

Sub-Urban Redevelopment

Rural mines and missile silos may be more common targets for underground reuse, but the appeal of adapting subterranean spaces is also starting to reach cities as well.

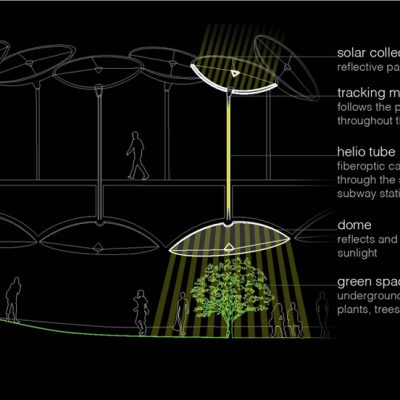

The Lowline is, in many ways, the opposite of survivalist silo bunkers, designed to be central, public and freely accessible. Recently approved by New York City, this project is on track to be the world’s first underground park, or at least: the first lush green one with sunlight.

This Lowline was conceived of as a complement to the Highline, a popular park also located in Manhattan. Each project re-purposes old rail infrastructure; while the Highline runs along elevated railway tracks, the Lowline is set to occupy an old underground trolley terminal.

The latter may initially sound drearier, but solar reflectors will pipe natural light down from above. And in a city where real estate is beyond expensive and new public space hard to come by, it makes sense to seek out opportunities both above and below the surface.

Just like old buildings, subterranean spaces come with their own mix of potential pitfalls and advantages. Where some see HVAC challenges, accessibility issues and egress nightmares others see natural weather-proofing, thermal mass, stability and security.

For now, most underground reuse projects are rural and involve extant voids, but that may change over time. As real estate in cities reaches ever higher peak prices, architects and developers are already being driven underground, excavating to facilitate urban expansion.

Comments (2)

Share

Can’t believe the UK’s Eden Project didn’t get a mention.

Awesome. But, of course, if you find a huge underground facility, and there’s a cat outside that glows green… then you definitely need to move!