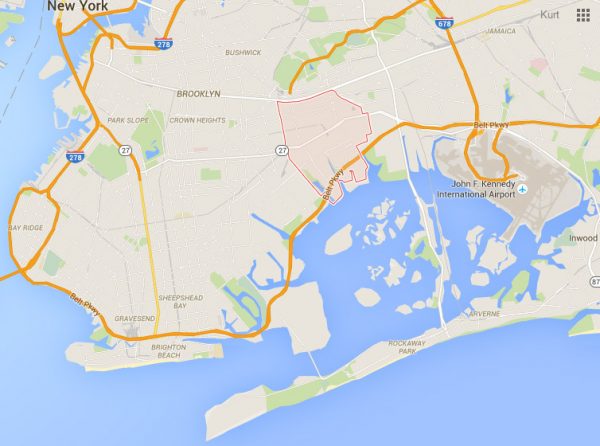

Neighborhoods are constantly changing, but it tends to be the people with money and power who get to decide the shape of things to come. New York City has an especially long history with change driven by landlords and real estate investors. Today, change is taking the form of gentrification, but in the 1960s, the neighborhood of East New York became a nexus of what has since become known as white flight.

The first developer to set his sights on East New York was John Pitkin back in 1835. Pitkin would lose his fortune in a cotton market crash, but not before launching this neighborhood into existence with housing and industry.

The Long Island Railroad came a year later, and with it factories to process foods from Long Island’s farms. The distinctive low-rise residential architecture that defines the area followed, then more rail lines connecting the area to Manhattan and the rest of Brooklyn. East New York became a thriving middle-class hub for the European immigrants working in local factories. It was, in many ways, a conventional white suburb, at least for a time.

In 1960 East New York was 85% white, but by 1966 it was 80% African American and Puerto Rican. Many of the whites moved out over a relatively short period to Long Island in the wake of national race riots and thanks to government subsidies.

At the same time, new immigrant populations came in seeking lower rents and spaces to live in a still largely-segregated country.

The remaining Caucasian population, meanwhile, banded together to resist immigration, forming an anti-black group called SPONGE (you can click the link if you really need to know what it stood for). Tensions were running high in the wake of rapid change.

Then on July 21st, 1966 a young black boy was shot and killed in an eruption of violence between incoming and existing residents. About 30 whites from SPONGE had started picketing behind police barricades. After a group of black counter-demonstrators formed, the SPONGE picketers broke through and gave chase. Things were heating up when suddenly, a gunshot was heard a block away from the action. An eleven-year-old boy named Eric Dean had been shot, was rushed to the hospital and died shortly thereafter. That night, groups of blacks began roaming the neighborhood, throwing bricks and garbage cans at storefronts and police cars.

In the face of further potential escalation, Mayor John Lindsay introduced a less-intrusive set of policies for police and managed to keep riots to a minimum in the months that followed. Still, none of this was enough to stem the tide of white flight from the boroughs, which continued to take its course and make room for incoming immigrants.

Scare Tactics & Predatory Lending

Brooklyn was in the process of absorbing two big migrations: southern blacks were coming north in search of industrial jobs, and Puerto Ricans were fleeing the decimated economy of their island. Segregation, however, limited migrant housing options, so neighborhoods like Bedford–Stuyvesant and Harlem quickly became overcrowded and newcomers began to look elsewhere in the city.

Landlords and real estate investors saw opportunity in the desperation of immigrant populations. They would come to hone two profit-driven tactics that would subsequently shape neighborhoods around the country: fear-induced white flight and predatory lending.

In the Cold War era of atomic concerns following World War II, the government pursued a policy of dispersing what were considered essential populations and critical manufacturing capabilities. Federal authorities began subsidizing mortgages and highways in what became a successful effort to relocate a certain class of (generally: white and educated) homeowners to soon-booming American suburbs.

Many fearful white residents (in places like East New York) jumped at the chance to buy homes elsewhere. Real estate investors took advantage of fear, using scare tactics and going door-to-door pressuring people to sell properties (also known as: blockbusting).

At the same time, most incoming renters and buyers were price-gouged. Over months and years, many were unable to afford to stay in their homes, often defaulting on rents and mortgages, enabling predatory lenders to make more sales. A cycle formed: sell, foreclose and resell. This process, in turn, perpetuated racial and economic tensions within neighborhoods, which played out in part through gang violence on the streets, leading up to events like the 1966 shooting.

Today, the neighborhood of East New York is quite varied, featuring green roofs on schools, multistory apartments, and elderly housing. With a population of around 200,000 and rents still cheaper than many other parts of town, it is one of the fastest-growing neighborhoods in New York City. Current residents have mixed feelings about incoming money fueling new development; they are excited to have funding for the community but worried about how the neighborhood may transform.

Meanwhile, around the country (and the world), similar stories of financially-driven change continue to play out in cities at the intersection of race, power, and money.

Comments (6)

Share

I live in East New york. My little brother is from here so needless to say this story hits close to home. I just want to put out that there are dope arts orgs that have been putting in work on the ground for years. one of them is Arts East New york.

http://artseastny.org/

There has always been good people here. Its sad that folks only take notice of ENY when gentification comes up. People been holding down ENY

Nice touch to do #212 about NY

I’m disappointed to hear this presented without any sort of commentary at all, some of the comparisons and basic economic reasoning were very shaky. That said, it’s a powerful piece and I’m glad to have heard it.

Thank you for sharing this story. I have one comment about the set-up for the piece. Roman states that black and brown New Yorkers were “neglected by both society and policy…”. I would like to draw attention to his use of the word “neglect”, as it removes burden of blame from those with power who shape policy. Perhaps a better phrasing would be “oppressed” by both society and policy. It’s a small difference, but language matters.

I was first interested to happen upon this article about East NY and then amazed by its content. Where to start?

Yes, ENY was a mostly white, largely Italian neighborhood until around 1955. I don’t know who wrote this not quite accurate article, which seems to have a pre-ordained interest in talking about white flight as though it were some kind of plague, but in 1955, a series of lower class housing projects were opened up in this neighborhood. Hundreds of lower class residents suddenly flooded ENY. There wasn’t even enough room in the local schools to accommodate this radical increase in the number of children. Many of the lower class residents were disadvantaged minorities, but a reasonable portion were white. But they were all lower class. None of this is even alluded to in this article.

Perhaps concerned that this dramatic influx would affect the value of their properties, or, may we even dare to say, their safety, the middle class (mostly but not totally white) residents of this neighborhood sought to leave. When they couldn’t sell fast enough and their properties became nearly without value, landlord owners of large buildings actually set fires in order to collect insurance money, which was the only value they could extract at that point, even if illegally gotten. The entire neighborhood became a blight–except for the housing projects from which no one could leave (too poor) or gain profit by burning. This only made the neighborhood more disproportionately poor and crime-ridden.

It is in fact this vast destruction of property (even some of the schools were razed after a time) that led to the more current day building of infill properties, perhaps under the pressure of growing real estate prices in the NYC area. Certainly, I am happy to hear it happen.

But I have to say, to write an article like this completely skipping over the substantial impact of this huge influx of people into a formerly stable neighborhood really does completely call into question any value to this piece. A story about that time in ENY would be more accurate if it spoke to the impact of such a drastic change of population through public housing instead of a topic of white flight.

Oh, and in case you are supposing that I and my family were part of the white-flight that this article simplistically discusses, you would be wrong. Although we were white, we were one of the families who moved into the housing projects at its opening, specifically the Cypress Hills Houses. Other nearby public housing was the Pink Houses and, a bit farther away, the Linden Houses. But the Cypress Hills houses were square in the middle of things. My family lived there for 10 years, from 1955 to 1964, and indeed so did my aunt and my cousin. And while we all benefited from a new public housing project, I would be both blind and deaf not to understand its impact on the people around us.

In 1960 East New York was 85% white, but by 1966 it was 80% African American and Puerto Rican. along with the new demographic came massive increases in violent crime.