The Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto reopened in 2007 with a controversial new addition dubbed The Crystal. This 100,000-square-foot extension was designed by internationally-renowned starchitect Daniel Libeskind. It is a dazzling composition of interlocking glass, aluminum and steel set at various angles. The angular design is about as different from the Italianate Neo-Romanesque original as any architect could possibly envision. “That’s the last time we hire two architects,” quipped one observer.

When adding to an existing structure, or building in a rich historical context, there is always a key question: to what extent should the new work look and feel like the structures around it? Does it make sense for the new structure to stand out or fit in? There is no single right answer, but there are extremes as well as hybrid approaches worth exploring.

Standing Out

In some cases, an explicit break from the fabric of the city and its historical context makes good sense in light of a building’s purpose, program and importance. A museum, for instance, might reasonably be expected to stand apart from its surroundings. Shape and style can signal cultural significance and contemporary origins.

In designing the Jewish Museum extension in Berlin (above), there was a strong reason for disruptive architecture beyond simply “standing out.” In this project, the aforementioned architect (Daniel Libeskind) had specific justifications for creating uncomfortable and sharp-angled spaces. The experience of the building is meant to be jarring at times, an “emotional journey” through the complex history of Jewish people in Berlin up to, including and after the Holocaust.

But when architects reprise similar aesthetic and spatial strategies for all kinds of structures, one has to wonder about the appropriateness of the repetition. Are the same slotted windows, vast voids and sharp-edged shapes suitable for all buildings, including shopping and leisure centers? At some point “standing out” becomes an artistic choice, failing to take into account the nature of each new site and program.

Libeskind is not alone in creating bold structures that seem to follow a signature style, repeating the same architectural themes. Frank Gehry is famous for his flowing metallic facades that first took shape around the Weisman Museum in Minneapolis, Minnesota.

Like his Deconstructivist colleague, Gehry has repeated this strategy in subsequent works over the years. Decades after his first metal-wrapped project, similarly warped exterior treatments can be found on his buildings around the world. These adorn museums but also concert halls, schools and hotels, seemingly without regard for place, purpose or relative importance in the built environment.

It would be all too easy yet simplistic reflect on these buildings and conclude that context-defying architects need to be reigned in. Some structures redefine cities and skylines in positive ways precisely because they break the mold. Paris, for instance, presents us with three convenient examples of city-defining buildings that were initially critiqued but ultimately accepted, becoming praised urban icons.

Most famous of all, of course, is the Eiffel Tower. It was widely ridiculed as an eyesore when it was constructed, and many thought it should be taken right back down. The structure has since effectively become the symbol of Paris (though not all Parisians have come to love it).

Similarly, the Centre Pompidou, designed by an all-star architecture team including Renzo Piano and Richard Rogers, was declared a “monster” when it was unveiled. Its inside-out approach puts circulation and mechanical systems on the outside, leaving open-plan space within for galleries. It has since come to be seen as innovative.

Designed by I.M. Pei, the glass-and-steel Louvre Pyramid was criticized when unveiled. The pyramid shape was seen as anachronistic, a work out of time and place (referencing ancient Egypt). Its use of modern materials was further critiqued for failing to take the historic French Renaissance museum building into account. Today, it is a landmark.

Each of these Parisian buildings visibly signals its importance relative to its surroundings. They make a case for standing out. Yet visual hierarchy can begin to break down when disjunctive approaches start dominating the urban landscape. Imagine a world full of buildings all designed to look new and different – it would be easier to see what is old versus new, but harder to judge relative civic significance. There is thus also a case to be made for contextual architecture.

Fitting In

At the opposite end of the spectrum, rote historical mimicry and façadism can be problematic as well for the legibility of a city. Urban landscapes are already complex and hard enough to comprehend without faux vintage structures further confusing things.

One context-centric way to build new things in old places is to simply gut interiors and leave existing facades standing. Preserving shells in this way maintains continuity of experience for passersby along public faces. Furthermore, it saves pieces of buildings that might otherwise be lost to history. Sometimes the facades are well-integrated with new structures. Other times a superficial minimum is maintained, just enough for architects to appease preservationists. From a strictly aesthetic standpoint, this strategy yields mixed results.

Such an extreme approach to “fitting in” can also compromise urban legibility as much as “standing out” can. If all historical facades were maintained or reconstructed, all buildings would simply look old. Also, their function and relative importance would be hard to identify at a glance. Whether facade preservation is useful or farcical is neither here nor there, but either way: it is not the only way of working with context.

Fortunately, “fitting in” can go beyond strict imitation and slavish preservation. Context-sensitive designs can be subtle, creating a visual dialogue between existing places and new construction. At the same time, walking a fine line between contextual and contemporary can be challenging as some architects have learned first hand.

New Beginnings

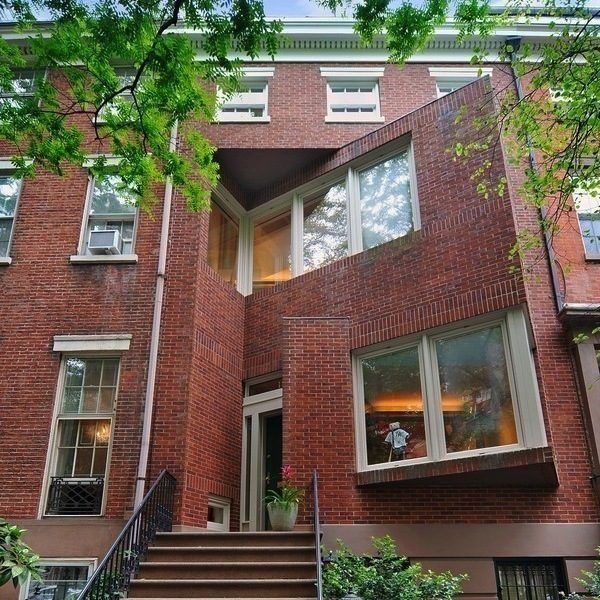

In the 1970s, a new townhouse was built on a controversial site in Greenwich Village and neither tradition-oriented nor modern-minded critics were pleased. The building that had previously occupied the site was a Greek Revival home from the 1840s.

This prior structure fell victim to an accidental explosion, triggered when Weatherman terrorists inadvertently detonated a bomb they were building inside. The whole townhouse was leveled by the blast. Traditionalists hoped for a historical reconstruction while Modernists thought a steel-and-glass replacement more appropriate.

Architects of Hardy Holzman Pfeiffer Associates were faced with a decision: they could (1) rebuild the house as-was (faking historical continuity), (2) construct something bold and new (but out of context), or (3) attempt to find a middle road between old and new.

In the end, the designers angled part of the front facade, giving it a dynamic twist. The resulting residence refers to its surroundings: it is built of brick, matches neighboring roof heights and features a row of top-story windows that continue adjacent patterns. At the same time, the building represents a clear departure from context due to its angled facade. Many critics at the time saw it as a failure, yet in compromising, the architects arguably managed to bridge old and new while simultaneously memorializing a significant disaster.

New Additions

Additions to existing buildings can pose an even more difficult problem to the architects tasked with their design. Such projects have to deal even more directly with adjacent contexts. Extensions and remodels are also far more common in already-dense cities than from-scratch constructions.

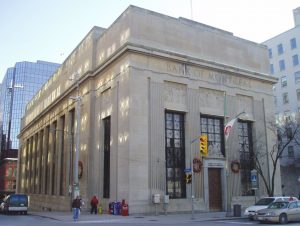

Originally built for the Bank of Montreal, the Sir John A. Macdonald Building in Ottawa, Canada, is a Beaux-Arts structure dating back to the 1930s. In 2012, the federal government commissioned a renovation of and addition to the original building. The designers were challenged with creating an extension that would be respectful of history but contemporary in form and function.

Architects from NORR Limited Architects Engineers Planners refurbished the old building and created an addition that (even at a glance) clearly relates to the original while just as clearly being new and different. The extension contains nods to the massing, materials, scale and details of the original while maintaining a degree of separation.

Old is divided from new by a glass-walled section. The secondary structure visibly defers to the original, thanks in part to a recessed facade at street level. In the words of one of the project architects: “The Annex is not meant to be a landmark in its own right. It’s designed to set up visitors to better appreciate the existing building.” The interior embodies parallel themes, balancing similarity with difference.

Old + New

The Rotermann quarter of Tallinn, Estonia poses a hybrid problem; its redesign involved additions, preservation and new construction. This industrial area of the city boomed in the late 1800s and early 1900s, home to thriving factories, plants and mills. In recent decades, it began to lose steam and become rundown.

In the redevelopment of the district, a design team from HGA (Hayashi – Grossschmidt Arhitektuur) set about creating a walkable mixed-use area. They designed an array of solutions, rehabilitating old structures and building new architecture alongside them.

Brick, limestone and weathering steel were used throughout, forming a consistent and context-sensitive material palette. At the same time, it is immediately clear to visitors which parts are old and which are new. A new steel addition (above), for instance, extends window lines from a rehabilitated stone facade below. The upper part is obviously an extension, but one that still relates to the original building.

Clearly, there is no single right approach to designing architecture across all contexts. Some places and programs might be best served with an outstanding new structure while others may call for something more contextual. Ultimately, as styles and tastes change, so will the ways architects, developers and civic oversight groups choose to deal with adding to existing built environments. If there is a single lesson to be learned, perhaps it is this: whether architecture stands out or fits in, it often turns out better when architects account for historical context.

Comments (7)

Share

Milstein Hall on Cornell’s campus is a good (?) example of a contrasting juxtaposition of old (Sibley Hall, one of the oldest buildings on campus) and new. It wraps around and juts out from Sibley, next to another older building. Definitely mixed feelings about it (but, appropriately, it is where the Art, Architecture and Planning Department lives).

http://www.ochshorndesign.com/cornell/writings/milstein-critique/images/fire9-01-site-photo.jpg

http://www.convergencedesignllc.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2011/12/Milstein-Hall_Cornell-Univ_OMA.jpg

https://designthebottomline.files.wordpress.com/2013/08/milsteinhall_cornell.jpg

I dropped out of architecture school because my of my restoration/renovation ideas. My final project of second year studio was to design a multi-family dwelling for a Chicago neighborhood. I decided to gut the interior of an East Pilsen two-flat and turn the ground floor handicapped accessible. Eventually I decided to tweak the exterior just to get the reviewers excited for a ‘new’ building design and guess what? When it was time to present, the reviewers didn’t like it. I bombed and failed because I was the only student out of the entire studio who was worried about historical preservation. A reason could be that buildings were designed this way because of the material at hand in history but that was kind of a reason for me to design it in the first place.

I’m afraid of the architecture that stands in front of progression. It’s full of light with cold steel and a mile high without any sign of ornamentation. If I can’t design without the Mona Lisa on my wall, I don’t want to design it at all.

So now I’m studying landscape architecture. Here, the professors actually understand me.

/r/iamverysmart

I’m curious about the choice of “legibility” here. Is that sort of standard for the profession or was that an analytic choice by the author? It just seems to imply that there is a coherent message or image that the city is meant to convey, and I don’t know if that’s true.

In terms of actual architectural lingo, conjunctive and disjunctive are somewhat more common terms (for fitting in and standing out), but still fairly academic. The choice of ‘legible’ in this case was not so much about architecture needing to fit together and form a coherent message across a whole city than a general legibility of parts.

You might think of it in terms of physical legibility or typography – as in: not the ability to form a complete overarching narrative but the actual issue of comprehending letters, words and sentences on a given page. We see ornate buildings set back with lawns and recognize them as civic and cultural institutions. We see a basic brick building with rows and columns of windows and understand it to be an apartment complex. Individually, these parts add up to a whole that is never strictly about one story, but can be more or less coherent when taken together (or apart).

Paris, for instance, is “beautiful” … but why? Some would say it is in part due to its aesthetic consistency of residential blocks punctuated by civic structures that stand apart. https://www.quora.com/Why-do-some-people-think-Paris-is-the-most-beautiful-city-in-the-world . But don’t get me wrong: I love chaotic and seemingly complex cities too. Still, even in the winding Hutongs of China there is a pattern, organizing principles and vernacular that help us understand what superficially appears like disorder.

Gotcha. That makes sense. It’d be interesting to look at how architectural choices embed power dynamics using arguments for “legible cities” (in the sense of presenting a coherent story–that of the dominant group)…

Thanks for your quick response–I love the work y’all at 99PI do!

Bravo on an excellent thought-provoking article. I’m not sure cities need to be legible to outsiders, but I am sure that contrast and continuity are equally important elements within the cityscape. Everything depends on the idea and the skill of its execution.