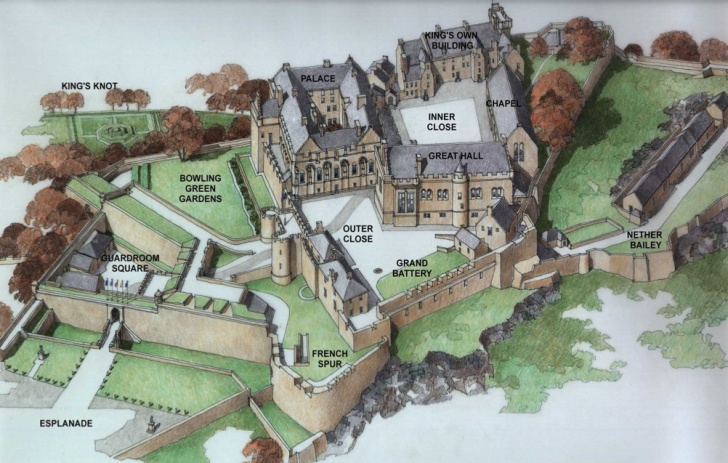

Stirling, Scotland is the home of Stirling Castle, a truly marvelous place that I love to visit, that sits atop a giant crag, or hill, overlooking the whole town of Stirling. There has been a castle on that hill since the 12th century at least, and maybe before, but the current buildings date from the 15th and 16th centuries.

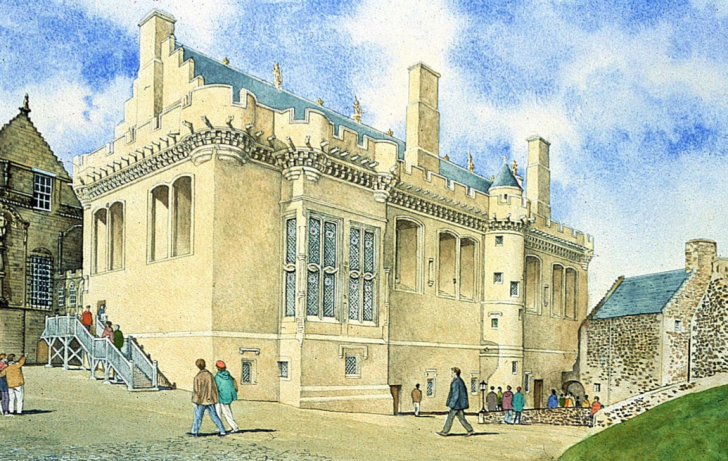

When we think of medieval castles we usually picture a grand structure, with subdued, dark stone masonry. But when you gaze upon Stirling Castle today from the town below, you will notice that one of the buildings is different from the others. Since 1999, after a decade long restoration effort that altered the building inside and out, the Great Hall of Stirling Castle has been a bright, cheery yellow.

But not everyone in Stirling is happy about that.

Most medieval castles were a collection of buildings, each with a specific purpose. A great hall is one of the key buildings in a castle. To quote Bill Bryson in his book At Home: “No room has fallen further in history than the hall. Now a place to wipe feet and hang hats, once it was the most important room in the house.” The Great Hall of Stirling was a huge gathering space where parliament would meet and set laws. They would also have lavish banquets and feasts in the hall.

The story of how the restoration of The Great Hall of Stirling Castle led to it being painted bright yellow illustrates the unexpected complexity in the art of restoration. It comes down to this question: when you choose to restore something, which moment in time are you restoring it to?

Historic Scotland is the government organization charged with educating the public and safeguarding Scotland’s historic treasures. When Historic Scotland took over guardianship of Stirling Castle in 1991, they found the Great Hall in an awful state.

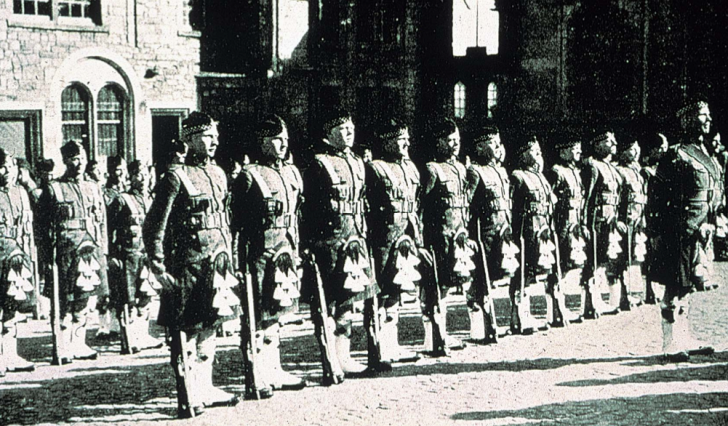

From 1800 to 1964 the castle was controlled by the War Office and it became the home of the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders. And they didn’t treat the castle as a historic artifact to be preserved. The Great Hall was used as barrack accommodation. Turning the one big, fancy room into barracks meant adding floors, altering windows, replacing the ceiling…really changing everything. Once the military left, the place was gutted. And when Peter Buchanan’s team at Historic Scotland took over in 1991 the building was a shell. They were left with a huge question mark as to what they were going to do with it.

The typical mandate of Historic Scotland is to preserve historic places in the state they were found, but The Great Hall of Stirling Castle required some drastic measures. The question was: to which period should it be restored? Should they preference the military period from 1800-1964 or the medieval and renaissance period? Strategically the castle has been important for hundreds of years. Castle Hill in Stirling overlooked bogs on one side, and the bridge over the River Forth on the other, so for hundreds of years it was the place that controlled trade for the whole region. And it was seen that the cultural significance of the period from 1600-1800 outweighed the significance of the military period.

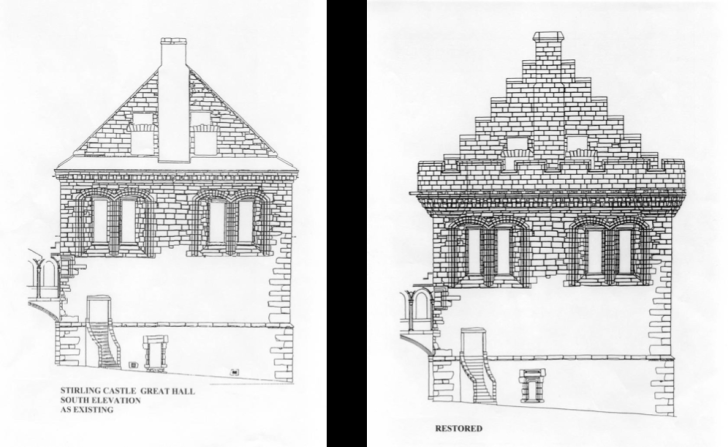

But choosing to restore the castle to a state 300-400 years in the past is not that simple. First of all, the records aren’t all consistent. The restoration team had a series of etchings of the Great Hall spanning from about 1600 to the late 1800s and they show the building from various angles. Unfortunately, they all show slightly different things. The etchings show different numbers of chimneys and different heights of chimneys. Traditionally the Hall had ridge beasts, heraldic statues of unicorns and lions that sit on the apex of the roof. All of the etchings show these, but they show different numbers of them. So the etchings give an idea of what the castle might have looked like, but as a tool for restoration, they weren’t much use.

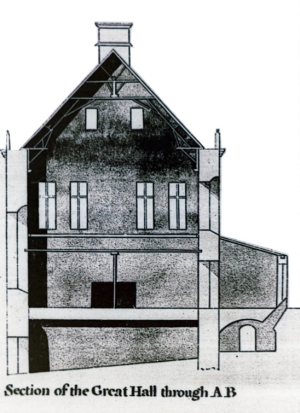

To help figure out where the ridge beasts should be placed on top of the building, they had to figure out the original structure of the roof. Sometime in the 20th century the roof had been completely replaced by the military, but the original hall had a glorious hammer beam roof. A hammer beam roof is a medieval technique that uses wood beams as a network of cantilevers and trusses on the inside to make the roof strong over such a big, wide open room. You can see all the timber when you look up from inside the hall. It’s stunning. It’s a jigsaw puzzle of beautiful triangles that are amazing to behold. Because the stone ridge beasts weighed ¾ of a ton, they could only be placed where the hammer beam roof was strongest. This is as true now as it was 300 years ago.

So the team had a hammer beam roof to construct, but they had no hammer beam roof left. They needed clues in order to get it right.

They found one diagram, a cross section of the hammer beam roof of the Great Hall from 1719, but since there’s only one record, it’s hard to know if it’s completely accurate. Since there was no other information about what the roof looked like, they began researching the surveyors from 1719 who drew the diagram, and found that other diagrams they drew of other castles were very accurate.

Historic Scotland decided to trust the survey from 1719 and rebuild the roof based on that.

Using the one historic document, they built the roof, which determined where the heavy, stone ridge beasts were placed on top. One discovery begat another, and another, and the historic building came into focus.

The hammer beam roof was completed in 1999. Everyone who sees it, including the Stirlingfolk, seem to agree, it really looks great. So far, no controversy.

It was when they decided to also restore the lime wash finish to the Great Hall that local people began to express their objection.

When Historic Scotland took over the castle, it was completely grey stone. But throughout the castle, in corners and covered sections, they discovered bits of the original lime wash. Lime wash is pure lime (calcium oxide) and it also contains earth-based pigments. It’s a coating that’s meant to protect the stone masonry. In the case of Stirling, they found a significant yellow ochre layer of lime wash. The yellow was very intentional at the time. Hundreds of years ago, the built world was basically grey and brown, but on this giant hill, there was a great yellow piece of ostentatious bling that signaled for miles that this was a place for a king.

“We did huge sample panels of the lime washes all around the building to show people what it might have looked like,” says Peter Buchanan. “And we brought a lot of people from the Stirling area to see this as well. Because what we were intending to do, based on the analysis and the information that we had, was to put the finishes back.”

When Peter’s team was putting on the yellow finish, the Great Hall was completely covered in scaffolding and plastic. This may have contributed to the intensity of the reaction from the locals once it was unveiled. It was a sudden and shocking change to a historic monument that the people of Stirling had seen every day of their lives.

As a tourist, though, visiting the Great Hall is quite thrilling. Its brightness brings the building to life, and makes us reinterpret our muted, and ultimately wrong, image of the past.

Comments (18)

Share

can’t listen to it here on the site, second episode this has happened. after clicking “listen” it responds with “error: request not found” still listen through iTunes so i’m not missing out.

Same here

They used a very similar yellow (and quite a bold red!) when restoring the museum of Edinburgh, too. I rather like it: http://www.urbanrealm.com/buildings/833/The_Museum_of_Edinburgh.html

Reminds me of the decisions on whether to leave ancient Greek statues in their current state or whether to restore them to their original, painted, kitschy version: http://io9.com/5616498/ultraviolet-light-reveals-how-ancient-greek-statues-really-looked

I much prefer the pure-white, empty-eyed, haunting look vs. the paint-by-numbers version!

I looked up the yellow hall and it’s gorgeous. It’s a mild stately yellow .

It’s faded significantly since its unveiling, but I agree, it looks good!

I really enjoyed this episode, thanks for putting it together. One small thing, though, is the end makes it sound like the colour restoration was a one-off. Whilst it might be that Historic Scotland doesn’t do that again with its properties, there is still a strong current in the conservation movement in Scotland that we should not accept all old buildings as drab grey. As well as the Museum of Edinburgh cited above, Greyfriars Kirk had its walls restored to yellow in 2003, and Fyvie Castle recently had its walls restored to its original pink(!) harling.

Restoration is always a case-by-case basis, but I wouldn’t say that Stirling Castle’s Great Hall was a one off. I think there’s a growing realisation that if we’re going to outfit a building on the inside to look ‘authentic’, then maybe the outside should be authentic too, as the inhabitants would never have let the harling fall off and leave the bare stone exposed. There are countless small domestic buildings (tenements, small houses) that have similarly had their lime harling and colour restored.

Forgot the links to those two buildings:

http://www.undiscoveredscotland.co.uk/edinburgh/greyfriars/

http://www.nts.org.uk/Property/Fyvie-Castle/

Hi Roman,

Similar to the situation when Jeremy Irons restored Kilcoe Castle (West Cork, Ireland) rendering it pinky/orange

http://www.irishexaminer.com/breakingnews/ireland/irons-peach-castle-annoys-neighbours-in-co-cork-13639.html

http://s0.geograph.org.uk/geophotos/03/71/63/3716335_eb0690b8.jpg

Keith

This was my first 99% invisible podcast that I have listened to, simply because it was in the featured list and I wanted something to listen to whilst on my lunch break. The weird thing is, my office is a five minute walk from Stirling Castle, it was a really cool experience to have something I’m so familiar with talked about. Thanks, I loved it!

Great episode. Google Street View has an interesting walk around Stirling Castle, including entering the Great Hall. Worth checking out for those of us who can’t get to Scotland immediately.

I don’t think that comparing Stirling Castle to the Statue of Liberty is justified. I thought the patina was actually part of the design. Didn’t Bartholdi take that into account and actually choose copper so that only over time the statue gained its final look?

As for restoring historical building, I don’t think that using original, bright colors should be discouraged. I see how a single restored building looks odd, when the rest of the castle wasn’t restored. But on its own it looks great. See the recently restored Wrocław Town Hall: http://i.ytimg.com/vi/3T5wRCwOGbE/maxresdefault.jpg. I think it looks stunning. The bright colors help emphasize some darker, stone elements and make the entire building stand out from the surrounding. Exactly how a seat of power should

The moist mouth sounds emanating from the woman is so irritating, i couldn’t finish this. This is a huge pet peeve of mine. Make Librivox audio books impossible to finish because at some point the narrator will switch to a person who sounds like a toothless person snacking on peanut butter.

Great story. My father, brother and I visited Stirling Castle in 1995 in the midst of a golf trip. My wife and I are planning another trip to Scotland in 2017 after I retire … this gives me a very good reason to revisit the castle.

I visited Stirling Castle when is was not coated yellow. It looked good in my opinion in its state of “degradation.” I believe a more accurate interpretation would be that it should be like gold in its final appearance. No one needs a doctorate in conservation to innately know that this is what was intended for the splendor that would make the unmistaken bold statement- the home of the Royals. It is simply and logically to be gold and not yellow- out of the mouths of babes. No doubt “restoration” is to put something back to its intended condition. But the “do nothing approach” should have won here if the decision makers didn’t know how to do that. I think heads would have rolled, (literally), in medieval times with the same reaction from the hierarchy and the townspeople In utter aghast if the castle were allowed to be left yellow. So all audio comments that lean toward people wanting to throw up is good and natural as an honest reaction like the body literally needing to throw up from the insult upon it from food poisoning. It isn’t right and it is obvious. Gleaming, worshipful gold makes sense, even though it may have originally been achieved by employing a lime finish using a lost methodology to turn it to gold, (kind of like the alchemy in copperice in lime washes), and not anxiously dare impose the wrong hue just to have done something. It’s a matter of national pride. If the Statue of Liberty were restored to shiny copper, with the knowledge that it would go to a chocolate brown until finally getting the Verde green color that all knew her to be, the people of New York and the world would be patient and understand. Stirling Castle will remain an eyesore until the second of the two enemies of conservation is honestly addressed. The first enemy is water which at least can be processed. The second and more wicked enemy is Ego.

Whomever can combat this effectively will rule the world. If Scotland wants to make that statement then the color will change.

Better a fingir aff as aye wag-waggin Fuils an bairns soud never see things hair duin. Rise above dear Scotland!!

Just listened to this podcast… In my head, I was visualizing a canary yellow, and was greeted with this look. It is the first shade of yellow I can say I really like. Great show Roman, it has hashed up the debate with my family and friends if the Statue of Liberty should have been brought back to the original copper and left to patina again, I am a fan of that idea.

Great show, thanks for the recommendations on other podcasts as well!

Southerland is a spelling mistake. It should be Sutherland.

I like the colour. As a child I looked up at the grey castle every day from my garden.

You all need to investigate ‘Mud flood’, it is huge on Youtube