People like to imagine that their favorite urban green space represents a pristine and natural refuge from the dirty and congested city. In reality, though, many spaces given over to greenery (especially in cities) are simply places no one can put buildings due to ground pollution ranging from chemical contamination to nuclear irradiation.

Toxic grounds are sometimes capped in concrete or simply topped off with clean soil, then turned into parks. This make sense to planners because a park limits individual-person exposure, versus having people continuously living and/or working on a hazardous site. Once turned into pastoral parks, most brownfields become something of a dirty secret, the truth of their history hidden beneath deceptive greenery.

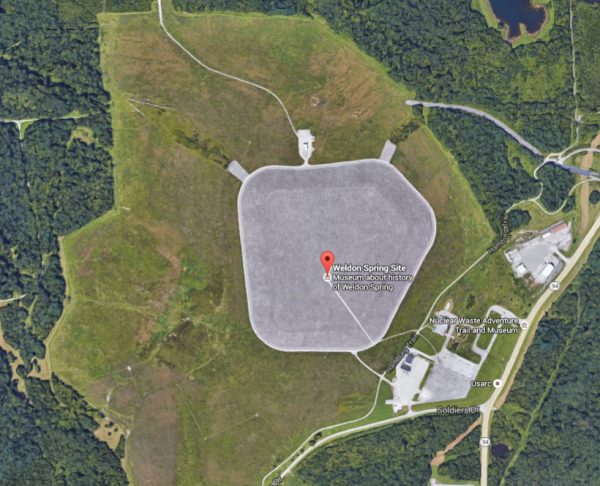

And then there is Weldon Spring, Missouri, home to 40 million cubic feet of hazardous waste put boldly on display. Rather than being dumped in a landfill in some remote place, this vast volume of refuse was entombed on the spot inside a huge climbable mound. Visitors can scale this micro-mountain or wind around it on a series of nature trails.

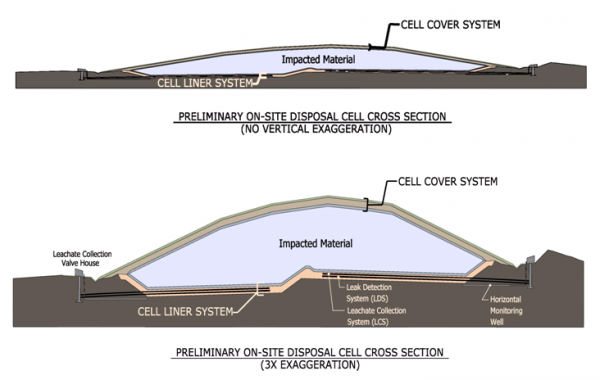

Constructed from layers of clay, sand, stone and concrete, and engineered to last for 1,000 years, this 45-acre monument to toxicity has become an unlikely tourist attraction. But it was not always such an open and inviting destination.

In the 1940s, the Weldon Spring Ordnance Works created explosives for World War II, byproducts of which began to contaminate the soil around the facility. At the time, it was the largest explosives manufacturing factory complex in the United States, producing more than 700 million pounds of TNT in its years of operation.

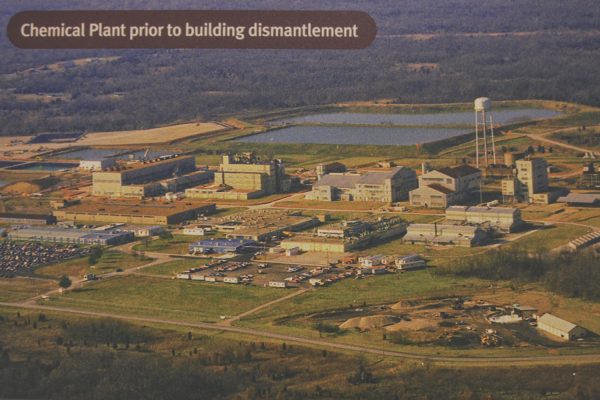

Then, in the 1950s, the Weldon Spring Chemical Plant took over a subsection of the same site and began processing radioactive uranium for the Cold War. For years, the adjacent Weldon Spring Quarry was used as a dump site for uranium, thorium and radium.

Next, in the 1960s, the government had a new plan, this time to use the same site for processing Agent Orange, a chemical (herbicial) weapon for use in the Vietnam War. This idea, however, was scrapped before yet another chemical could be added to the increasingly toxic mix.

Still, it was a bit late to be thinking about ways to keep this site clean, as illustrated by this DOE Summary of Weldon Spring’s status in 1969:

“Asbestos insulation was hanging from abandoned overhead piping. Power lines were left on teetering poles. Chemicals were left on laboratory shelves, many without labels. Thousands of rotting drums with contents unknown were scattered throughout the site. Contaminated materials were left inside the buildings and contaminated debris from various U.S. Department of the Army and U.S. Atomic Energy Commission operations were strewn throughout the site. Many of the buildings had caved in roofs and leaking pipes. 26 acres of raffinate (waste) pits contained contaminated water, and were cluttered with thousands of unidentified drums, and hundreds of tons of rubble from earlier decontamination activities.”

Finally, in the late 1980s, the Environmental Protection Agency raised concerns over the potential spread of various contaminants into local drinking water sources. In the early 1990s, the Department of Energy stepped in with a bold plan to create a toxic material disposal cell and invite the public to tromp around on it.

Thus, the 1,000-year Weldon Spring Site Remedial Action Project Disposal Cell was created, which is essentially a giant 45-acre cap on the whole polluted landscape. The Weldon Spring Interpretive Center was set up in a building once used to check workers for radioactivity. Today, it serves as a museum, educating travelers about the site.

Visitors are encouraged to hike up to a viewing platform on the disposal cell. At they top are a series of informational plaques and seats plus visual access to natural sights on all sides.

“Rest on the benches and enjoy the view of St. Charles county and beyond. You can see the Gateway Arch to the east on a clear day [and] the new hike and bike trail … running parallel to the Weldon Spring Site Interpretive Center.”

Other disposal cells can be found around the United States and the world. Still, this one stands out, explicitly designed to attract hikers, bikers, stargazers and birdwatchers.

Comments (4)

Share

This is a great episode! A great film companion to this: http://www.intoeternitythemovie.com/.

Amazing episode! For those interested, here is the a great film companion to this episode: http://www.intoeternitythemovie.com/

I grew up in Blairsville PA where there was a neat site outside of town with rocks, metal and various other dumped things. A 12- year old rock hound, I brought back some items and stored them in my basement. Back from college, saw a gravel mound and fencing- learned it was a Superfund site, radioactive waste from the 1920’s-era radium production facility in Canonsburg PA. I’m 58 and no cancer yet.

Some things have gotten better over time.

Zoom out just a little bit on Google Maps and see my high school! We were sharply instructed by our parents never to use the drinking fountains. In the early 90’s I was able to do my science fair projects in conjunction with some of the industrial hygienists at the Weldon Spring site. We really had no idea of the magnitude of this pollution we were practically sitting on.