In a world of online design competitions and social image sharing, many architects have taken to crafting ever more extreme models and renderings for public consumption. Some have even started covering their rendered buildings, from groundscrapers to high-rises, with gorgeous-looking trees. The effect can be breathtaking, but are these designs truly green or simply a fresh form of greenwashing?

The architectural motivations behind this trend are myriad. Vertical greenery gives a structure the appearance of sustainability. Greened towers suggest better air and a greener view both for building residents and the city. The brightly-colored renderings appeal to intrigued investors as well as sales-oriented developers.

Accordingly, representations of future skyscrapers with unlikely greenery are on the rise. The trend started with rooftops, but has grown to encompass all kinds of horizontal building surfaces.

Despite their visual appeal, many of these “treescrapers” will never get off the drawing board, let alone the ground.

For starters, the construction hurdles are daunting. Extra concrete and steel reinforcement are required to handle added weight. Irrigation systems are needed to water the plants. Additional wind load complexity has to be taken into account.

After installation, trees are also subject to high winds at altitude (but you never see them bent in renderings). The wind can also interrupt photosynthetic processes, while the heat and cold wreak havoc with many species of tree (especially tall, lush and lovely-looking ones).

Consider, too, that buildings have sides: the idea of putting the same trees all around, irrespective of wind and sun conditions, makes as little sense as finding trees equally on all faces of a mountain in nature.

And, of course, someone has to trim, maintain, replant, fertilize and clean up after all these living things as well.

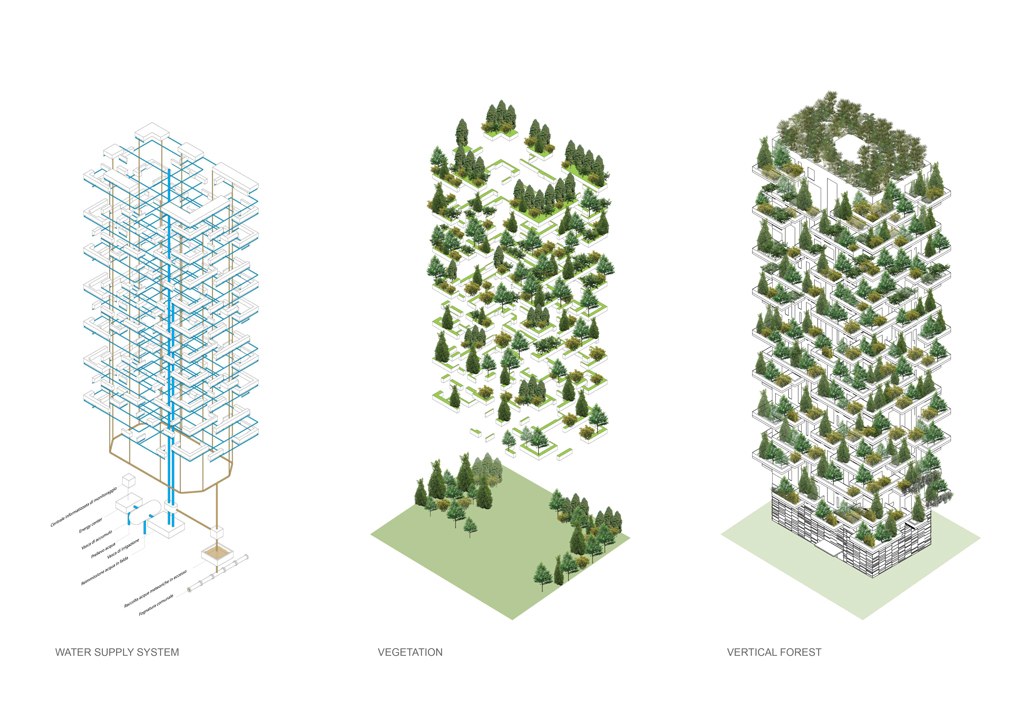

A recently completed pair of buildings in Milan, Italy, called Vertical Forest, is a rare example of a finished project in the realm of largely-unbuilt treescraper concepts. Designed by Boeri Studio, the project consists of two residential towers, each a few hundred feet high and supporting an impressive array of plants. The plans called for nearly 1,000 trees, 5,000 shrubs and 10,000 additional smaller species.

This greenery was added in part to help filter air, reduce noise pollution and provide shade but also to support habitats for various species of birds and insects. The structural specifications had to account for root systems, plant weights and a central system for irrigation.

The towers have been considered a success in many regards. The project was granted LEED Gold, in part for its solar panels, won the Highrise Aware in 2014, and was named the 2015 Best Tall Building Worldwide by Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat (CTBUH).

“The Bosco Verticale is a new idea of skyscraper, where trees and humans coexist,” says architect Stefano Boeri. “It is the first example in the world of a tower that enriches biodiversity of plant and wildlife in the city.” In short: the world’s first real vertical forest.

Critics, however, are quick to point out that the embedded energy involved in structurally supporting the trees (and hoisting them into place by crane) significantly offsets sustainability gains. Other reported problems include: higher than expected costs to tenants, structural issues with some specific trees and general construction delays.

Then there is the contrast between the drawings and actual structures. While the finished works, viewed independently, are impressive in their own right, they do not exactly look like the lush forested facades seen in the proposed designs. Perhaps there is a seasonal element, or the trees need time to grow and fill the space. Still, even on the website of the architects, a rendering remains the lead image, not a photo.

In some photos of the completed project, a plant in the foreground creeps into view. One starts to suspect the close-up tree’s role is to visually reinforce the presence of its sparser cousins above. The project still looks good in the end, but it looks significantly different than the visualizations, especially when it comes to the greenery.

This divergence of rendering and reality is not a one-off phenomenon; it is inherent to any tall-building project involving trees, and especially ones that propose much taller tree-topped towers.

We all know intuitively that a building will never look just like a drawing (architects often omit things like railings on balconies for a sleeker facade). Still, this particular trend may be getting out of hand, creating unrealistic expectations and leading to unsustainable solutions.

In the real world, between groundbreaking and ribbon-cutting ceremonies, most buildings will get at most a single tree during a “topping out” celebration. This Scandanavian tradition has ancient roots (possibly a way to appease displaced tree gods) and involves temporarily adorning the tallest beam of a structure with a conifer.

Beyond that token tree, however, extensive green coverage (a thinner layer supporting mosses, succulents, herbs and grasses) is often much more practical than intensive (roofs or balconies with shrubs and trees).

For extensive projects, the demands are lower for water, nutrients and ongoing management than they are for intensive ones. Structural requirements are also reduced: engineers need to account for just 15 to 50 pounds additional per square foot (for extensive) versus 50 to 150 or more (for intensive). For context: a normal balcony might be required by code to support 40 to 100 pounds per square foot, so an intensive green roof could more than double the engineering demands.

Yet even the thinnest green coverage requires a growing medium, filter fabric, drainage layer, insulation, waterproof membrane and more. Naturally, too, these flatter green surfaces tend to make for less attractive drawings, particularly wide-angle views at a distance. So for developers trying to sell units with impressive renderings, an extensive approach may seem less marketable even if it’s more sustainable.

There is a bigger question at the heart of this treescaping trend as well: what role should green space serve in cities?

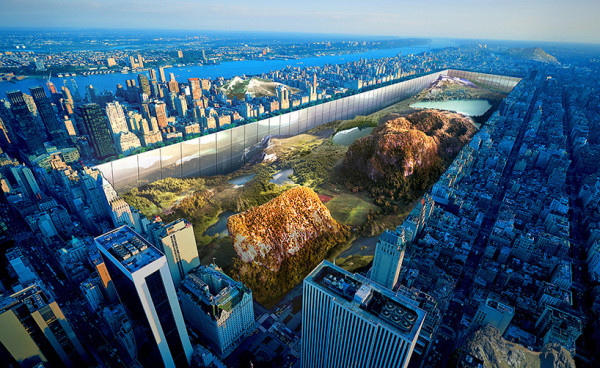

A controversial recent design concept to wrap Central Park in a glass “sidescraper” was broadly criticized in part because it partially cuts the park off from the city, creating semi-permeable barriers between landscapes and citizens that need not exist.

A treescraper approach potentially suffers the same problem, but magnified: it lifts trees out of shared public spaces entirely, putting them up where they can be seen by many but enjoyed by few. Thus removed, they become more like window dressing, green ornaments rather than social activators. Civic greenery is a great asset to urban environments, but perhaps best when grounded in reality.

Comments (27)

Share

All excellent points. One thing the author doesn’t mention, but I’ve always wondered is who is supposed to take care of these trees (watering, raking, pruning, etc.)? And what happens when the trees die or branches start tumbling off the side of a skyscraper? It seems analogous to buying bunnies at Easter or a pet alligator- might seem interesting at the time, but in the long-term you’re taking on a lot of work and potentially a lot of headaches…

Right, that should be the first question when implementing greenery into a design– who is going to maintain it? More often than not, extensive greenery introduced into projects is only successful if someone is there to take care of it.

The renderings are impressive but once you start to recognize that every plant on it is a flat, 2D cut out, the real thing starts to look much better, even if it doesn’t have as much green. :)

I wish this article did more to explain why green buildings are impractical. So dirt is heavy and plants require care. That never stopped anyone from building a swimming pool in a condo. I’d like to see cities in the future where trees are so commonplace in the urban environment that no one mind some up high, because they’re up high and down low all over. But I’m not an architect, maybe that’s not possible… This article suggests that, but didn’t give enough explanation as to why.

As a Landscape Architect we are often the ones designing these green roofs but have little voice in how they are shown in the renderings. Anything is possible with green roofs, but everything must be planned including structure of roof to support the growing medium, irrigation, soil composition and an important maintenance schedule after construction is done. The initial planting of almost any project will not look like a fully grown lush roof. It takes years to reach that stage requiring proper maintenance.

moar articles

No quibble with the structural arguments, but let’s not be too cynical about why green covered buildings are being sketched. It’s more than a desire to make pretty renderings. I see it as an attempt to re-conceptualize skyscraper living as a lifelong, family-friendly option. An attempt to cast very tall buildings as something other than either (1) coldly beautiful dens for singles and oligarchs, or (2) cramped, subdivided warrens for everyone else. By ostentatiously greening them, the designer is saying that this is a place for more than just struggle and excess, but also a place to simply be alive, to make a life. To be sure, these buildings are usually a vision of luxury, aimed at the rich but not super-rich professionals trying to make a run at lifelong urban living, but they are also a natural (“natural”) response to the simultaneous contempt for the suburbs and desire for space to breathe.

Thanks – I confess I had not really paid much attention to the subjectivity of the way vegetation is rendered and used on models and concept drawings. Though I have often wondered about the practical requirements.

Clearly, even when they get built as conceived, ‘treescrapers’ are, without a lot of careful planning, going to be just another way for buildings to age badly.

But this is not a new problem – just a different form of an old problem – failing to include entropy as a design factor. (And in the hands of a great designer entropy can be an opportunity as much as a constraint.)

It seems to be a function of both materials and form – and the result is really bad when designs use both materials and forms that don’t age well.

There is also a signal to noise ratio in play. Entropy adds noise to the design. In some buildings that seems to be assimilated by the signal – the architecture itself – and they age well. In others it just creates the ugly.

I think that is why many people like older decorative styles. Those busy neoclassical and baroque shells can absorb a lot of noise.

Green buildings are in many ways a move back to an older aesthetic – one that privileges the surface of the design. The structure still provides proportion, balance, energy, but the aesthetics of green buildings, like old banks and town halls, are on the surface.

When stone ages it can be beautiful in a way. When gardens die and wither, or just run to seed, they are miserable and depressing.

Great points – it is as much about entropy, maintenance, materials and aging as anything.

A designed landscape must account for inevitable entropy (landscapes grow, change, die can look good doing it). “Shrubbing up” buildings is not sound and the rendering look ridiculous. What are they trying to hide? Bad architecture. I think there is room for more green, well planned green walls, roofs and more but it can’t just be decoration.

The picture in the Wikipedia Article for that building in Italy looks pretty good to me

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bosco_Verticale

Doesn’t look like a rendering

It looks fine, it just doesn’t look like the renderings. The dark building color blends in with the trees, making it look like there is more tree cover. If you zoom in, it has about half the tree cover shown in the renderings.

I think one thing you might have forgotten is that trees and vegetation needs time to grow. The building was only finished in 2014. 1 or 2 summers are not a lot of time for the green to establish itself. I’ve seen amazing green balconies, but they definitely took longer to grow than 2 years. Also the picture you are using for comparison looks like it was taken in early spring, when not all trees are fully covered yet. And looking at the picture source – could it even be that the pictures were taken in January?

By the way, I am huge fan of your show and been following for many years. Also I believe that architecture and architecture rendering face a lot of issues and lead to a lot of bad designed buildings and cities – so I wish there would have been a stronger example in this article.

If you look at more recent pictures of the buildings, things have filled in a bit, but they still don’t look like the early renderings where tree coverage blocks almost the entire building. If you scroll through the architects’ portfolio pictures for the project, you can see a quite start difference. That said, I agree that more rendering versus reality examples (beyond treescrapers) would be good to explore – perhaps in another article down the line!

There is a lovely building in Fukuoka, Japan which was built in the 1990’s, that has a whole side covered in mature trees and plants. You can walk up stairs amongst the greenery and the green side faces a park. It is only about 20 stories high at most, but a great example of a successful tall building with a growing garden or forest.

Hopefully great thought will be given to how these building will age, and even greater care will be given to construction.

Improper installation of waterproofing, drains, and root barriers can cause problems (moisture intrusion, staining, concrete lifting/cracking, rust, mold growth, etc.) in single-story structures. If not done properly in a high-rise, we’re talking Irwin Allen material. Also, better keep kids and pets from climbing those trees!

Woah! I’m really enjoying the template/theme of this site.

It’s simple, yet effective. A lot of times it’s very hard to get that “perfect balance” between user friendliness and appearance.

I must say you have done a superb job with this. Also, the blog loads super

quick for me on Opera. Outstanding Blog!

It takes patience and much nurturing to pull off these kind of projects. I don’t think that renderings are accurate these days. I also think however that the project you selected is way too early for giving comparisons.

Every thing lies in maintenance! The amount of work it takes to keep these glass facades clean is also expensive. Id rather have some greenery on my 18th floor balcony then have only glass. The technology has improved leaps and bound for Green roofs so its archaic to talk about 20 ponds extra per sqft as a big issue.

Again its all about maintenance. That’s what sets these projects apart.

I work in a very simple office tower in Seoul. We have a roof garden with small trees (3m tall) shrubs and other plants. The access to this space is limited because there is no direct elevator to the top, just the emergency stairs on 17th floor, so only workers here know about it. The main reason we have this space is just the urban regulation that dictates a minimum of 15% of landscape for any building. Due to the cost of land and profitability, most projects maximize the coverage ratio on the ground floor, which in most cases cannot provide the minimum landscape area by law, so part of the landscape need to be located in upper floors. So, we are enjoying a roof garden because of the law basically. Most investors and clients just want to make cheap buildings to maximize their profits, and do not care at all about making a better environment because it costs more. I do not care if the render is not exactly as the finished building. Mcdonalds use renderings as well and the burger you get is not the same as the picture. My point is that green spaces in a building are better than nothing, and should not be a discussion issue anymore.

Reply to your question about Bosco Verticale maintenance in this video

These are the arborists taking care of the Bosco Verticale’s trees. One team of gardeners for all the greening system, since ever. It costs less than you think.

https://vimeo.com/142010218

Pictures were taken in 2015

http://milano.repubblica.it/cronaca/2015/10/03/foto/milano_giardinieri_volanti-124234286/1/#11

Laura Gatti, Bosco Verticale’s greening designer and consultant

Interesting subject. As a person who has rendered designs and implemented them, the final product rarely looks exactly like the rendering. Value engineering, design changes, and engineering constraints are all factors. The initial idea is flashy and intended as a marketing product. I’ve always been told to take “artistic licensure” with renderings. The client doesn’t want to see stick trees, 1 gallon strubs, and dormant grass. They want to see their site design at its best, which sometimes will not be a reality until plants mature years later.

Such a wonderful subject. As an environmental designer who works in landscape fields, I always face with clients (Architects) send me renders and request for construction advices, without any realization of plants and their needs, not even the basic ones. the worldwide green-skyscrapers trend lead architects to design such a beautiful and imaginary sketches that catch all hearts, but in construction phase most of them have to be ignored due to its cost, position and specially climate situation that would change the concept. And ridiculously it’s considered as landscaper’s lack of capability not architects knowledge limitation (if not everywhere at least its common in IRAN!!). Also I worked with architectural teams that come a long with plant natural rules and try to have innovation in architecture with all limitation of working with plants that were to interesting and useful.

Also I admire Bosco Verticale, it is a real extraordinary project that I always describe all the notes and gaps in green-skyscrapers for my clients with that. It is a great real example for the way of species selectin, plant size and the way the box details have to be and comprise differences between renders and reality. I wish we could have more examples like this.

Thanks for such a subject.

This is very inspiring to me! I love these renderings, such artwork! As a horticulturalist I always envisioned a time when man might not be around and the plants take over the buildings, but this is much better!

I would like to say, of my time practicing architecture, the concept of a treescraper came as a rejection of the steel and glass skyscrapers that are cold, monotonous and lifeless. Adding trees was a way to bring in nature and life into a place where direct access to green is impossible on higher floors. With land being more expensive and public green spaces being scarce, there isn’t much space for the green spaces as we hoped for.

I do acknowledge that having plants and trees in tall buildings is hard to achieve and maintain, but it’s not impossible to create well-designed green buuldings. Ken Yeang has been designing eco-architecture for years and he has some great examples of having careful planning of green landscaping and consideration of the ecosystem in the building. It’s a shame that his works are not mentioned here, he is a leading architect in eco-architecture design. Most treescrapers don’t turn out as well mostly because most tend to just copy the look of the design (ie. adding trees in the building) rather than understanding the meaning behind the design (ie. why put a tree there, where to put it to get the best sun/cool the building, what species to put). Mostly it’s developers that wants a look of a treescraper without understanding the meaning behind it, but i know architects are guilty of it too.

As for reality not looking like the renderings, i would just like to say that gardens or parks don’t start out looking like they do now, those also take years to fully mature and grow into what they are now. Renderings show the future possibility of the building, and not a cheap gimic to fool the people.

The idea of trees in skyscrapers is not something we should condemn, rather we could see it as an effort to create more soft green spaces in a hard grey environment we have now. I believe that technology would improve to make treescrapers more feasible in the future, and one day the renderings would become reality.

I’m confused by your “either/or” mentality about this. Buildings having trees does not “lift” trees out of parks. It adds trees to buildings. And of course things don’t look like the renderings. Partly, that’s an idealistic form that should be understood as what the building could look like when all the plants grow in lush and healthy and well tended, not immediately after being hauled hundreds of feet through the air. You make valid points about the wind and sunlight, which should be taken into consideration. But otherwise, this entire article is a confusing jumble of unfounded criticism for a concept that (gasp) would clean city air. Why trees on buildings instead of parks? No one is saying that. The real question, is why not both?

Although I agree very much with the overall discussion of the amount of trees included in renderings vs the final outcome, and the difficulties in accomplishing their visions, i feel a lot of this discussion was put on the designers.

Although it is very important for them to drive the vision and concept of what is possible i feel a big part of it should be down to the developers themselves. They want to create a design that can be sold to the local community/government for planning and the prettier it is, the more the locals can get from it the better.

However the clients are usually, post approval, going to look at how they can reduce costs. One part of that is the reduction of the greenery on the building, but another is how much of the ground floor is given to ‘public space’. (Which I feel, if memory serves, was discussed during episode 09) but generally, developers want to give as little to the public as possible, and even when it is open to public there are ways to make it feel private to direct its use at certain clientele. This often changes/reduces the design of the greenery due to upkeep etc and overall cost as its not specifically beneficial to the people using/renting the building and gets cut out easily as the project is progressed.

This tends to be the bigger cause of reduction from original renderings than the designers vision/ability overall. I think it could make an interesting discussion.

Looks wonderful and has many positive advantages but I have a real concern.

Isn’t this more dangerous than flammable cladding (as on Grenfell Tower in London)? Only one tree needs to catch light from lightening or fire within an apartment, and the flames would leap up and down the building. I hope I’m wrong.