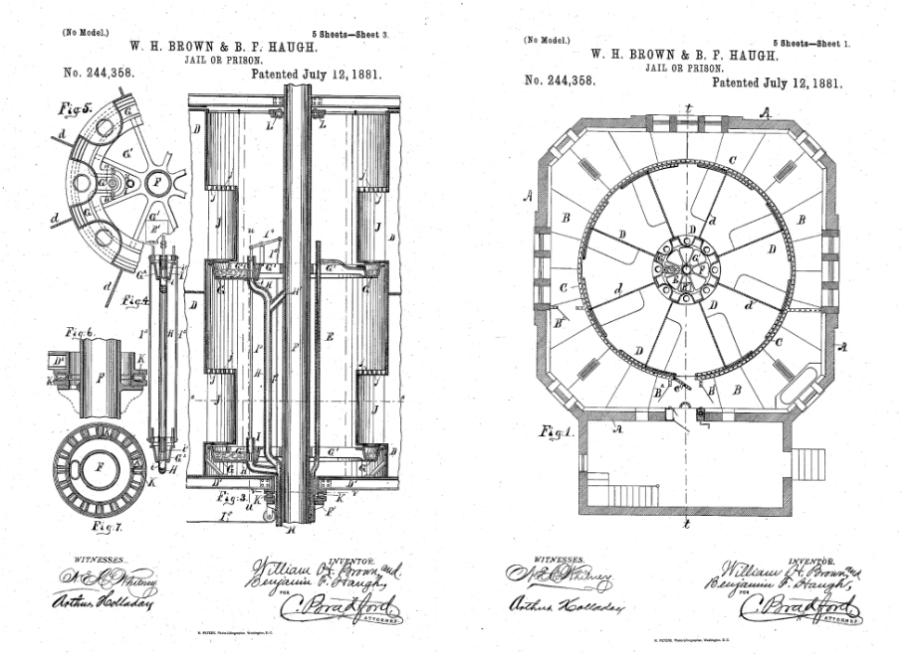

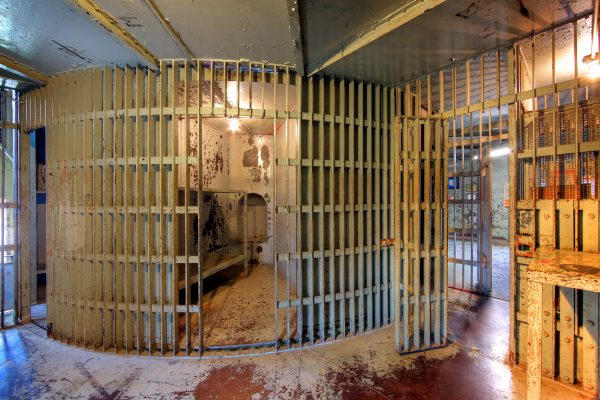

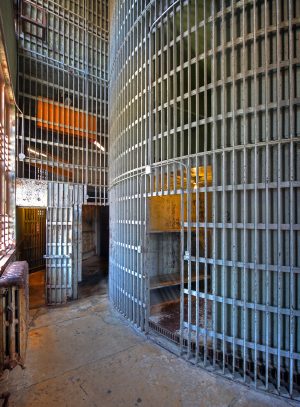

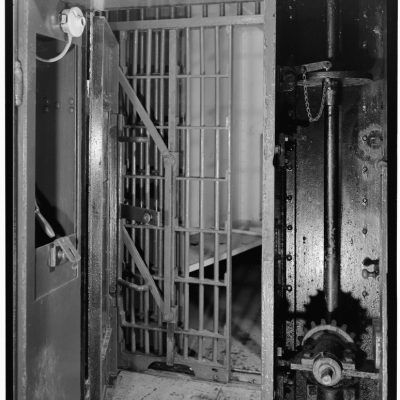

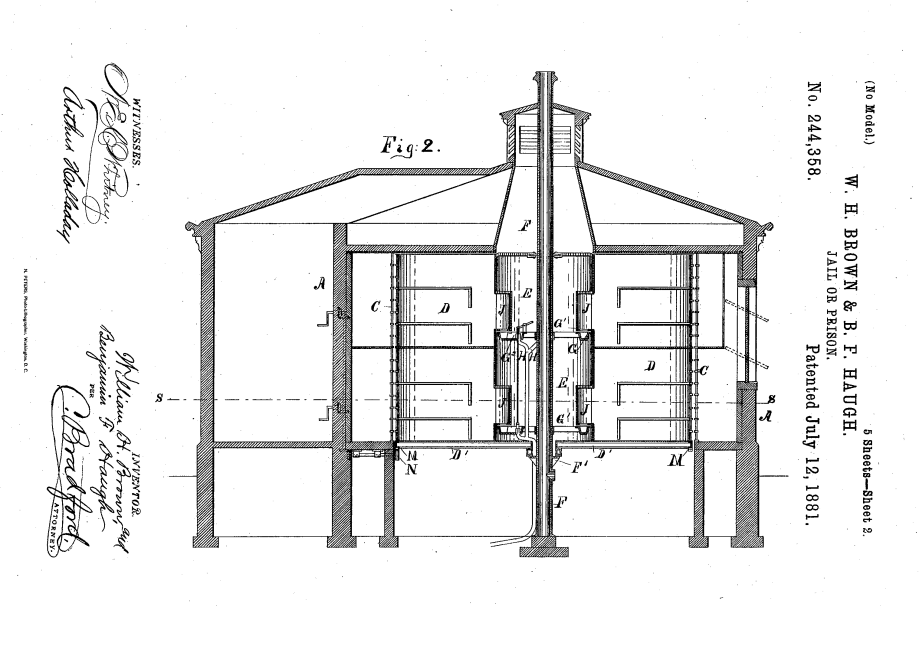

Like some twisted version of a traditional festival ride, rotary jails were anything but fun. Patented in 1881, they were invented to create better security in local lockups. Their rotating architecture consisted of a series of wedge-shaped cells surrounded by a circular barred enclosure with only one opening. Prisoners moving in and out could only do so when their cells were spun to align with that solitary portal, reducing escape opportunities. Strangely enough, the actual cells themselves rotated, not the bars. For decades, the design configuration was sold to (and bought by) small towns across the midwestern United States.

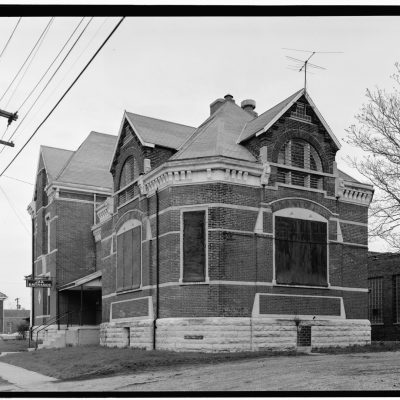

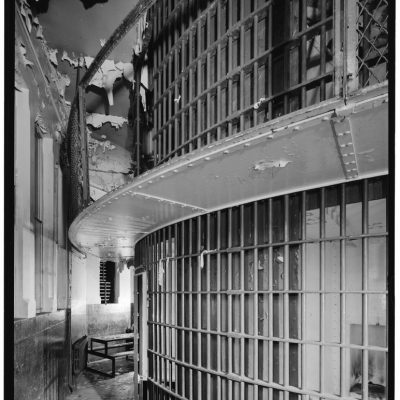

Shown above, the first rotary jail built is located in Crawfordsville, Indiana. While in operation, its 32-ton carousel of sixteen cells (eight on each of two levels) could be guarded by just two men. A reduction in required labor was a big selling point of the setup.

Only one person was needed to operate the hand crank and rotate the cells, using a mechanism much like the one employed to turn trains around on their tracks. Coal burned in a mechanical space below the cells would provide heat for the incarcerated during winter months. Individual plumbing in the cells was also an unusual luxury at the time, though a necessity given the difficulty of getting people in and out.

Per the original patent (No. 244,358): “The object of our invention is to produce a jail in which prisoners can be controlled without the necessity of personal contact between them and the jailer or guard.” The system “consists, first, of a circular cell structure of considerable size (inside the usual prison building) divided into several cells capable of being rotated, surrounded by a grating in close proximity thereto, which has only such number of openings (usually one) as is necessary for the convenient handling of prisoners.”

The Crawfordsville jail was built in 1882 and operated continuously until 1973, though its rotating mechanism was disabled in 1938 (then re-enabled when the place was converted into a museum). In total, somewhere between a half-dozen and eighteen rotary jails were built based on similar plans over the decades following the initial patent. One, nicknamed the “Squirrel Cage,” was three stories tall.

Safety concerns, however, quickly led these various rotary jails to stop spinning. Limbs of convicts, for example, would get caught between the bars as the cells moved. Fire danger was also a consideration; in an emergency, inmates would have to be evacuated one at a time. The cells also tended to lack good ventilation and natural lighting. In many cases, the jails had to be retrofitted; rooms were generally welded into fixed positions and openings were cut in bars for individual cell access.

Inverted Panopticon

Given the unusual shape of the rotary jail design, one has to wonder whether this circular incarceration strategy was inspired in part by Jeremy Bentham‘s infamous Panopticon. In the 18th century, Bentham, an English philosopher, proposed a plan that would allow a single watchman to keep an entire prison population in check. His ideas would go on to influence prison architects for centuries to come.

The layout of a Panopticon is straightforward: cells are arrayed around the sides of a huge round building and a single watchtower is placed in the center. Never knowing whether they were the present target of observation, convicts would (according to Bentham) always assume they were being watched and (presumably) behave accordingly.

Many subsequent prisons borrowed surveillance strategies from this design but the most complete version was constructed in Cuba more than a century after Bentham developed the idea.

Both Fidel and Raul Castro spent time inside the Presidio Modelo (Model Prison) complex built in the early 1900s – Fidel would in turn go on to imprison “enemies of the state” in the same complex. This network of circular prison buildings held over 8,000 political prisoners at its peak.

Rotary and Panopticon designs have some design elements in common. Each employs circular layout strategies to reduce the need for guards and increase prisoner compliance. Each approach is also highly novel, seeking to revolutionize the way prisons are planned.

Still, while there are superficial similarities between rotary and Panopticonic prisons, they are also opposites in many ways. The construction of a Panopticon is a relatively conventional architectural project while a rotary jail requires complex moving parts. Also, the personnel reduction in rotary jails comes not through implied observation but physical barriers. If anything, the layout of rotary jails (with observers on the outside) actually makes it harder to keep tabs on all prisoners at once.

Indeed, the more one looks at it, the more the rotary approach appears like an absurdly complicated solution to the relatively straightforward problem of small-town incarceration.

Perhaps the biggest mystery behind the rotary jail is also the most fundamental: why should it rotate to begin with? Even granting the potential advantages of allowing access to only one cell at a time, there are other ways to make that work. The bars, for instance, could spin on a track around the cells, rather than the cells themselves needing to move … or a system of interlocking mechanisms could be employed to allow just one cell to open at a time.

Whatever the reasons, they were compelling enough to convince a number of towns to adopt the rotary jail model. Yet they were also insufficient to justify keeping the paradigm in motion. In the end, putting the breaks on these warped merry-go-rounds was seen as a safer and more efficient strategy to help stop the cycle of crime.

Comments (1)

Share

That’s a fascinating strategy to keep prisoners in their cells. This is the kind of thing that a town regrets building a few years later, but thanks their lucky stars for about 50-100 years later. This kind of unique tourist site will always be able to draw people.