Just under 20 years after it was built, a seven-story office building shaped like a basket is being abandoned by the company that created it. At its peak, the structure housed 500 Longaberger workers. Its audacious design was derived from the company’s Medium Market Basket. It served as a giant-sized advertisement for this core product. The 180,000-square-foot facility is now on the market for $5,000,000.

While it may be a bit gaudy and impractical to some would-be buyers, this building is often cited as a classic example of a particular design dichotomy. Specifically, it is what architects Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown would call a “duck” as opposed to a “decorated shed.”

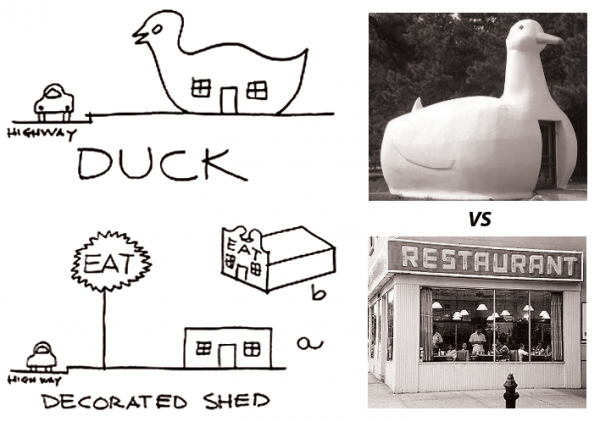

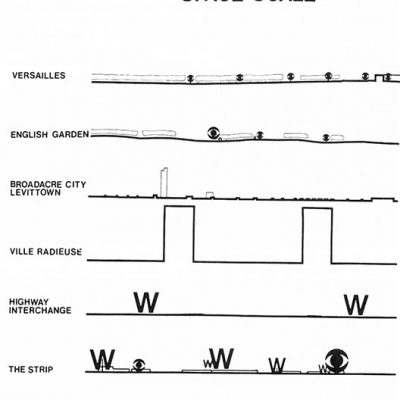

In essence, “ducks” are buildings that explicitly represent their function through their shape and construction. This typology is defined in opposition to “decorated sheds,” which are generic structures with added signs and decor that denote their purpose (think: big-box casinos, roadside hotels or restaurants with big signs).

The duck typology takes its name from an actual duck-shaped building: the Big Duck located on Long Island in New York. The structure was built to house a shop selling ducks and duck eggs. The form of the building itself explicitly tells passers by what they will find inside.

- Ducks: “Where the architectural systems of space, structure, and program are submerged and distorted by an overall symbolic form.”

- Decorated Sheds: “Where systems of space and structure are directly at the service of program, and ornament is applied independently.”

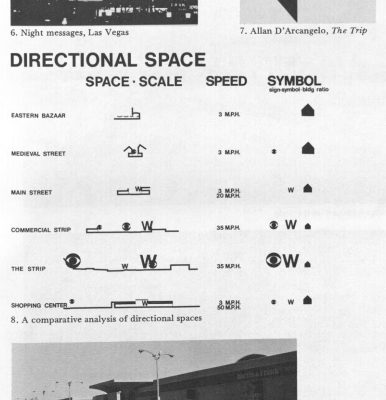

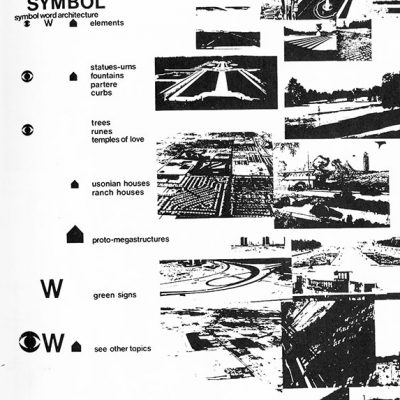

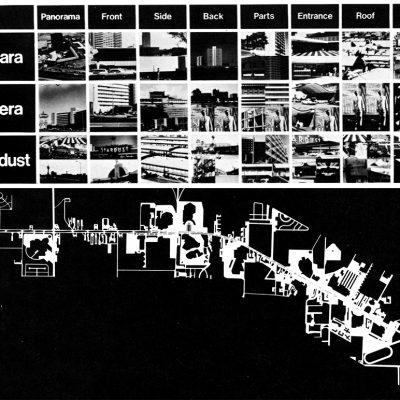

Venturi and Scott Brown developed the distinction between ducks and decorated sheds while studying the Las Vegas Strip in the late 1960s and early 1970s. At the time (and perhaps still today), the idea of architects studying such a commercialized place designed for the masses was unusual if not outright scandalous.

Learning from Las Vegas

Where other Modernist professionals saw a wasteland of kitsch and pseudo-historical decor, Venturi and Scott Brown found rich layers of meaning in the symbolism applied to otherwise-boring buildings.

In a way, Sin City represented a return to pre-modern architecture; attached signs conveyed the purpose of everyday buildings and ornamentation enriched the visual expression of special structures.

“The commercial strip, the Las Vegas Strip in particular…challenges the architect to take a positive, non-chip-on-the-shoulder view. Architects are out of the habit of looking nonjudgmentally at the environment, because orthodox Modern architecture is progressive, if not revolutionary, utopian, and puristic; it is dissatisfied with existing conditions. Modern architecture has been anything but permissive: Architects have preferred to change the existing environment rather than enhance what is there.” – Learning from Las Vegas

Robert Venturi, Denise Scott Brown and Steven Izenour published their findings and opinions in Learning from Las Vegas. The book was controversial, galvanizing other contemporary architects to stake out sides in the ensuing years in the battle between Modern and (what would come to be seen as) Postmodern approaches.

Beyond Sin City

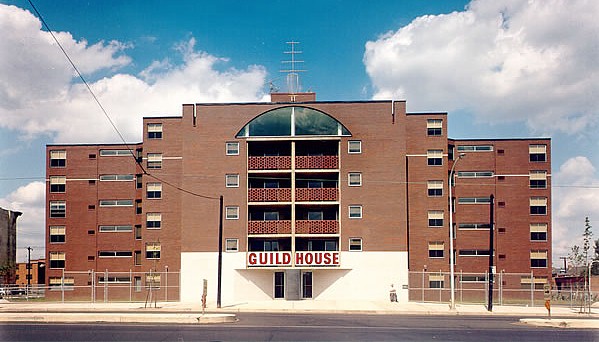

Venturi, Scott Brown and Associates, meanwhile, were inspired to integrate signs and symbols into their firm’s creations. Completed in Philadelphia in 1963, the Guild House building features an array of historical references, signs and symbols. This project would come to be seen by architectural historians as an early work of Postmodernism.

“In Guild House the ornamental-symbolic elements are more or less literally appliqué … The symbolism of the decoration happens to be ugly and ordinary with a dash of ironic heroic and original, and the shed is straight ugly and ordinary, though in its brick and windows it is symbolic too.” – Robert Venturi

Designed to house elderly residents, the structure borrowed elements from Classical orders and featured structure-specific signage integrated into the facade. Among other controversial elements, a prominent golden antenna was placed on the roof. This was a reference to the inhabitants’ presumed main pastime (watching TV).

Needless to say, this finishing touch was subsequently removed. Still, this building was significant in its attempt to reclaim the rich complexity of historical architecture found prior to the Modern movement.

“When it cast out eclecticism, Modern architecture submerged symbolism. Instead, it promoted expressionism … of architectural elements … structure and function. By limiting itself to strident articulations of the pure architectural elements of space, structure, and program, Modern architecture’s expression has become a dry expressionism, empty and boring–and in the end, irresponsible. Ironically, the Modern architecture of today, while rejecting explicit symbolism and frivolous appliqué ornament, has distorted the whole building into one big ornament. In substituting ‘articulation’ for decoration, it has become a duck.” – Charles Jencks

In championing “decorated sheds,” Venturi and Scott Brown criticized Modernism as a misguided attempt to create “ducks” through structural and programmatic expression. If a minimalist building sounds like the opposite of a giant roadside duck, consider this: both are cases of “form follows function.” This key adage is closely associated with the International Style era of early Modern architecture. A giant duck, one could argue, takes the idea of “form follows function” to a literal (if absurd) extreme.

Some critics have since challenged the duck/shed dichotomy or conclusions drawn from it. Still, the theories and writings of Venturi and Scott Brown continue to be hugely influential. Learning from Las Vegas is still required reading at many architecture schools today.

From the neo-eclecticism of Postmodernism to the expressiveness of Deconstructivism, a great deal of contemporary architecture can be traced back to reactions against Modernism. Whether they view historical decor as cool or kitschy, designers today still struggle with whether or how to use ornamentation in contemporary architecture.

Comments (5)

Share

So if the Longaberger Basket building is retained but no longer sells baskets, then does it go from being a duck to a decoy? Love the show.

I realize the point of this story wasn’t to list examples of ducks, but I couldn’t help but think of Ice cream stands shaped liked ice cream cones! There’s a lot of them and they didn’t come up as an example when I googled “duck buildings” after listening to the episode. I was also thinking about temples in Asia that are built to symbolize an ascent to heaven, could these be ducks as well?

That’s a good point. Are all religious buildings ducks. I’m thinking of all the modern churches I’ve been in that don’t need to be shaped the way they are to house worshippers. But are actively choosing to have large roofs, non functioning steeples and bell towers, and stained glass.

Just found a “Duck” building…I’m visiting Baku, Azerbaijan and their Carpet Museum is shaped like a rolled up carpet. I had never heard of a duck or a decorated shed building before, but now I’m on the look out. Thanks for the story!

“Venturi, who died Tuesday at 93, might have been the most influential architect of his era. Alongside his wife and partner, the architect Denise Scott Brown, he helped lead a rebellion against the austere stylings and grandiose pretensions of midcentury American architecture. If Mies van der Rohe, doyen of the International Style, counseled “less is more,” Venturi’s riposte was “less is a bore”—or as he wrote, using the positive language of the practicing architect he was: “More is not less.”

https://slate.com/business/2018/09/robert-venturi-architect-las-vegas-lessons-obituary.html