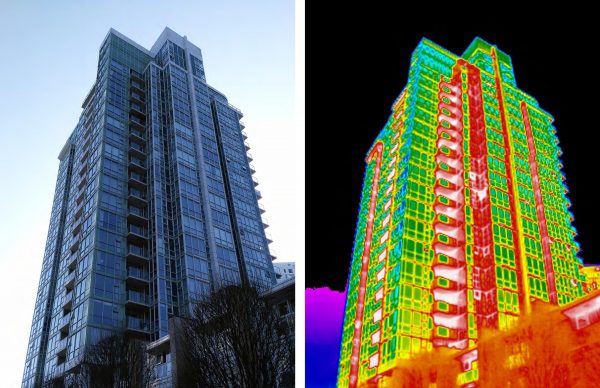

Glass has gone from a symbol of vertical growth on steel skyscrapers to a symbol of urban wealth on luxury condo buildings. Floor-to-ceiling glazing is a feature frequently boasted on idealized renderings used to sell new units in cities like Vancouver. Using that much glass, though, comes with a variety of issues and side effects, including thermal discomfort and energy leakage. Designer Genta Ishimura has a vision for mitigating these downsides while also creating new physical space for residents, all by wrapping exoskeletons around extant structures.

“The beauty of windows is that they’re a part of architecture where individuality is and can be celebrated,” Ishimura told The Tyee. Historically, windows have come in all kinds of shapes and sizes and served a wide variety of purposes. Whether they are picture windows in small houses or panoramic skyscraper portals, they frame critical connections between interiors and the outside world worthy of thoughtful, site-specific design. While floor-to-ceiling variants may seem attractive in the abstract or when seen at a distance, actual occupants often close their curtains to create a sense of privacy and enclosure. What looks good from the outside isn’t always ideal for people inside.

Ishimura, who recently graduated from the University of British Columbia, used his graduate thesis as an opportunity to explore ways windows work (or fail to work) in existing structures. He then took things a step further with a redesign strategy for existing facades.

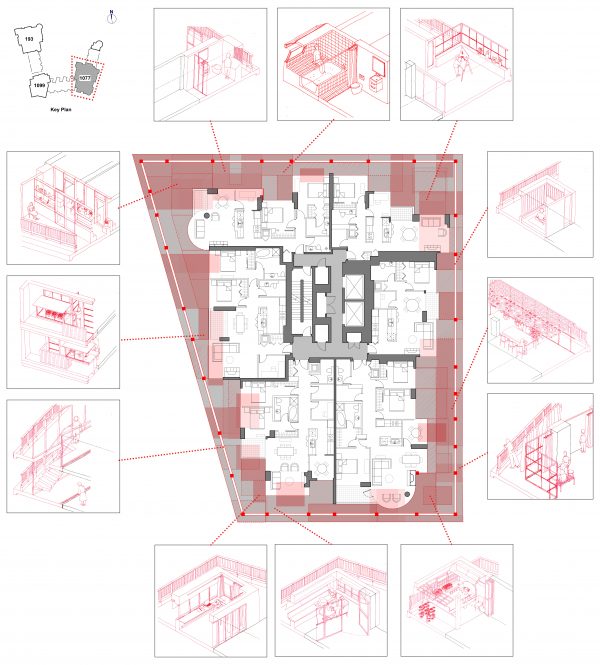

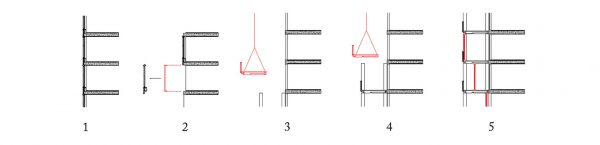

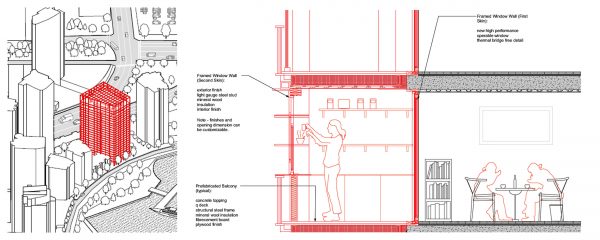

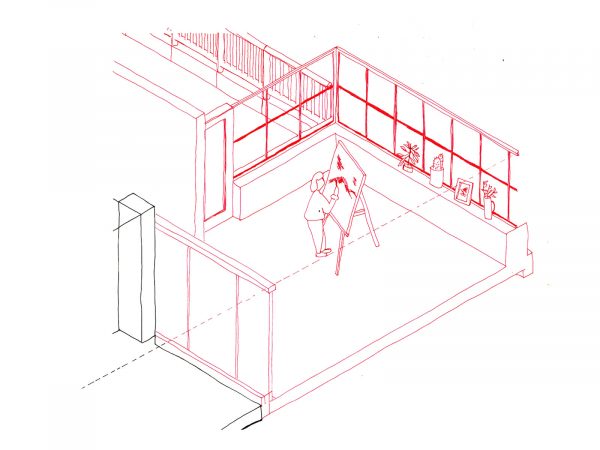

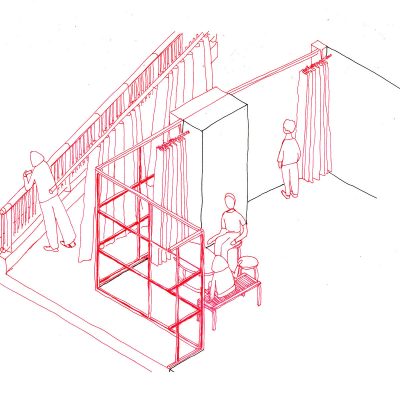

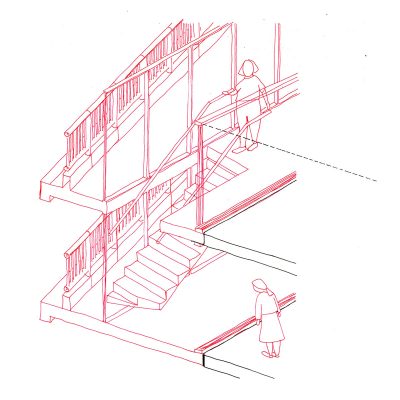

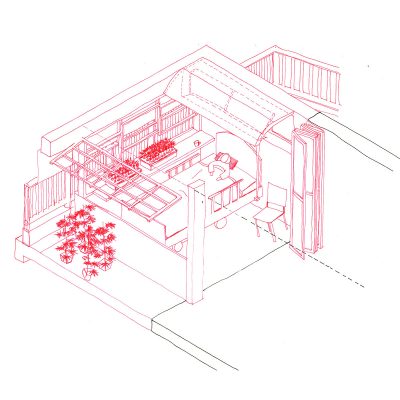

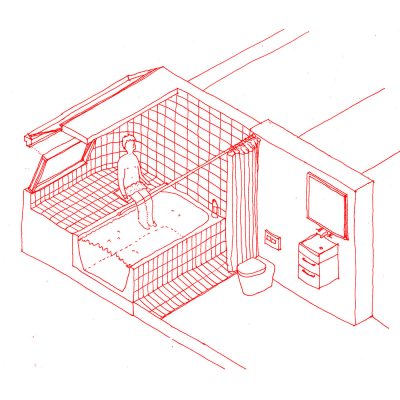

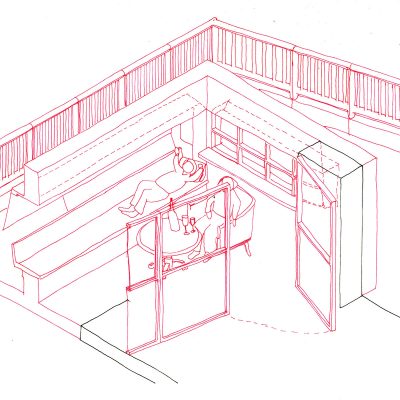

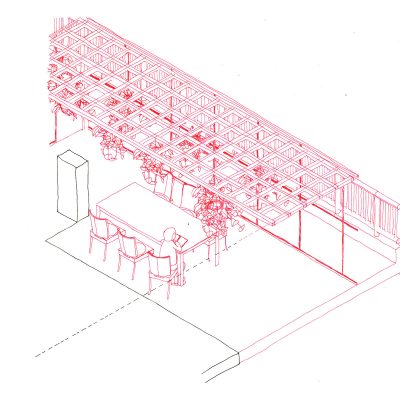

In essence, his proposal involves replacing existing windows on target buildings then installing and enclosing balconies as a kind of “second skin.” This creating shade as well as a thermal break layer between inside and outside — a space that mediates between temperature-regulated indoor areas and the natural conditions outdoors.

To gauge feasibility and explore how this might work out in practice, Ishimura selected an archetypal tower in Yaletown, Vancouver. With this real building as a research focus and architectural backdrop, he started detailing construction options and new potential uses.

Sometime in the next 20 years, the building in question is expected to require over $10,000,000 in envelope repair, regardless. One could reasonably ask whether there would be a better way forward using the funding already expected to be used for this purpose — a way to not just fix but also future-proof facades. Ishimura also points out that Vancouver offers incentives to green building developers, and could be amenable to providing similar benefits to green exoskeletal retrofits.

There is precedent, too, for this kind of remodel. French architects Lacaton & Vassal did something along similar lines to a set of vintage housing blocks in Bordeaux. Instead of razing and rebuilding, creating waste and adding cost, the buildings were outfitted with an external layer of winter balconies and gardens. Prefabricated modules were lifted into place in a matter of days. As reported in The Guardian, people put this added space to all kinds of new uses: “balconies are decked with plants, parasols, bikes, birdcages and assorted domestic minutiae.” Unlike complete interior overhauls, residents in this case were also not displaced during the construction process.

Not all buildings can or should be saved, and no one solution fits all problems, but projects like this show there are ways forward that can save time, money, energy and old structures at the same time.

Leave a Comment

Share