A few years back, I moved into a Sears building — no, not that famous skyscraper in Chicago, or one of those department stores in the suburbs, but a city block-sized brick behemoth just south of downtown Minneapolis, Minnesota. Formerly known as the “Sears, Roebuck and Company Mail-Order Warehouse and Retail Store,” it was a distribution center for an empire that revolutionized commerce in the 20th century. Today, it plays a new role in the post-industrial age, as do a series of similar-looking Sears “plants” in cities around the United States.

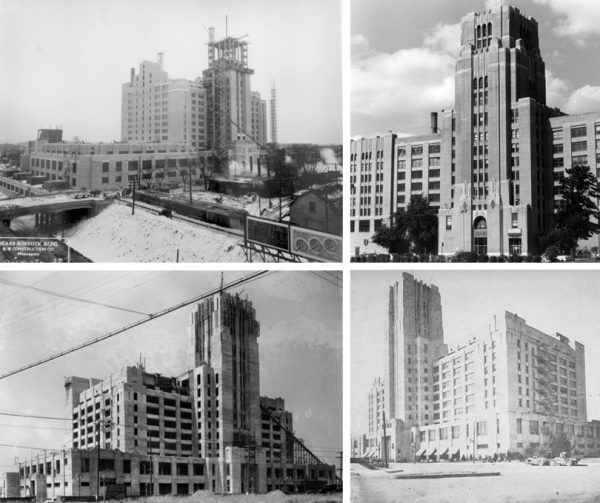

Built along a train route in 1927, the Minneapolis structure served its corporate purpose for decades. It was abandoned in 1994. Growing up, I used to bike past it along overgrown rail tracks, sunk into a trench to bypass road traffic above. Then, the early 2000s, the 1.2 million-square-foot Art Deco building was reborn as the mixed-use Midtown Exchange. Its main-level Midtown Global Market features boutique shops and eateries. Above are floors of offices, apartments and condos.

The winding commercial areas on the ground level are cozy, more like a bazaar than a mall, with a larger pub and a few sit-down restaurants around its edges. On the weekends, people gather for theatrical and musical performances in shared interior and exterior spaces.

The adjacent rail line, once convenient for shipping wares to and from the facility, has been converted into a bustling greenway for pedestrians and cyclists. These branching paths serve as spokes for a new hub of urban activity, connecting west to Uptown (and a series of local lakes) as well as east to bike routes along the Mississippi River.

And this building isn’t alone: similarly massive “plant” complexes (many of which look uncannily like this one) can be found around the United States, and some have been adapted to new, place-specific uses. Most are easy to spot, featuring Art Deco details and a tall central tower (designed to conceal a huge elevated water cistern). Some have been demolished over the years, but others have been remade, adapting to and becoming reflections of the cities they inhabit.

From Rural Mail to Urban Retail

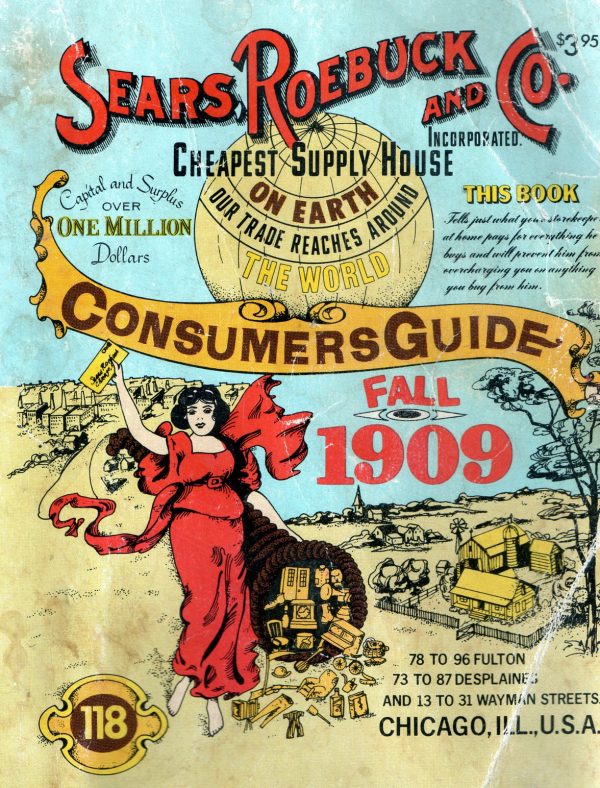

Long before Amazon became a product-shipping juggernaut, Sears connected a nation of mail-order consumers with manufacturers and wholesalers. Born in Minnesota, founder Richard Warren Sears started off selling watches in 1886, later expanding to offer jewelry and other products by mail and moving his operation to Chicago. When it came time to branch out from catalogues to stores in the 1920s, Sears started adding retail outlets to warehouse and distribution centers.

Many of the Sears plants built during this urban boom period were cut from the same architectural cloth. They were boxy and wide with big windows and distinctive central towers, an aesthetic that can be traced back to one particular Chicago architect.

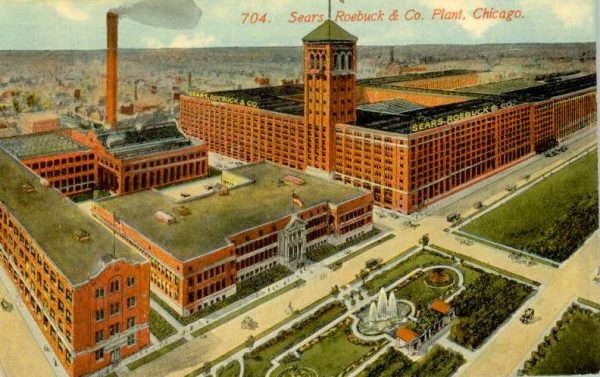

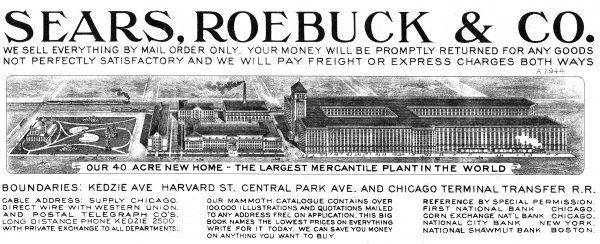

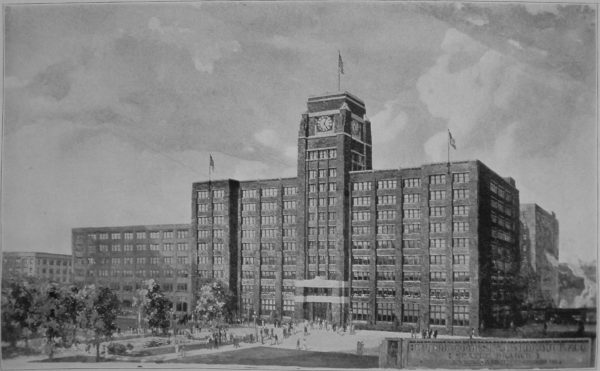

George Croll Nimmons was close with Sears, Roebuck and Co., even building a mansion for the company president at one point. For a time, Nimmons practiced at Burnham & Root, one of Chicago’s most famous architecture firms. Then, with a partner, he got a commission in 1904 to design a warehouse, distribution and administrative center for Sears.

It was in many ways a prototype of the other Sears plants that Nimmons’ firm would erect around the country, spreading out from this central corporate hub in Chicago. This version featured dark red brick and stone trim (later models would turn toward Art Deco).

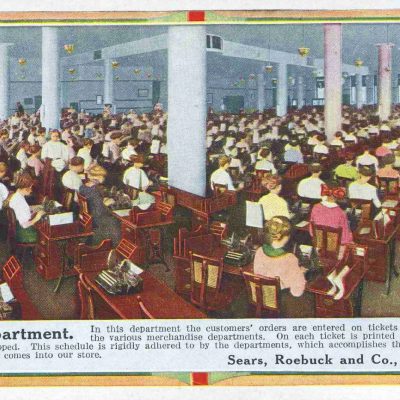

The gigantic, multi-block creation was reported to be the largest mercantile complex in the world at the time, not to mention the biggest architectural project in Chicago history. It was the Sears corporate headquarters and heart of its mail-order business.

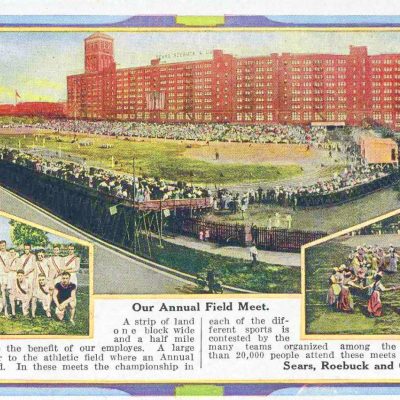

The sprawling complex was effectively a city-within-the-city, complete with its own infirmary, a private bank for employees, a company fire department and a dedicated power plant. Sears even used the tall tower at its heart as a broadcasting base of operations for the company radio station: AM-WLS (short for “World’s Largest Store”).

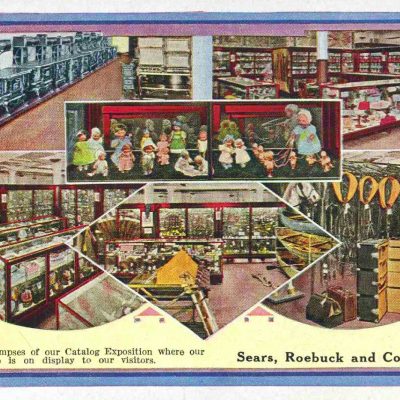

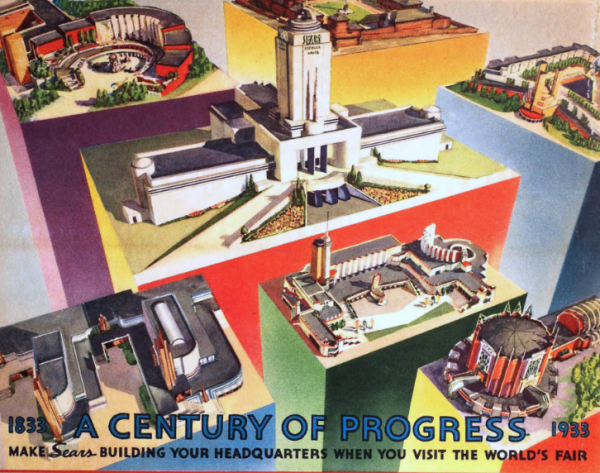

Nimmons would go on to design a variety of additional plants like this as Sears rose to become a brick-and-mortar titan. His firm also planned out the futuristic Sears, Roebuck & Co building for the 1933 Chicago World’s Fair, featuring corporate exhibits demonstrations.

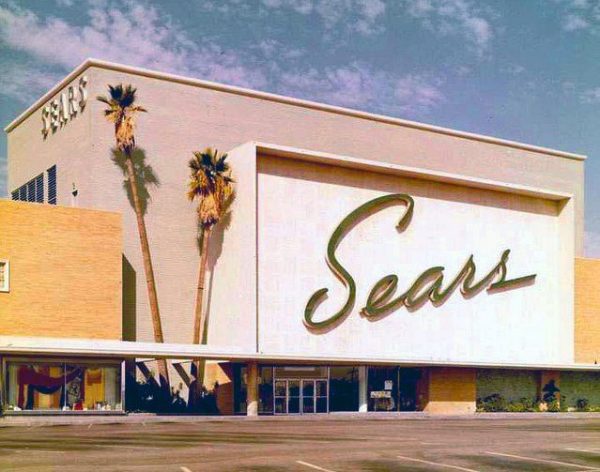

From Urban Plants to Suburban Malls

The Chicago complex remained the headquarters of Sears until 1970, when the Sears Tower skyscraper (later renamed Willis Tower) was completed downtown, setting another new record: world’s tallest building. This skyscraper was a bit of an anomaly in the development of Sears, though, which had been shiftings its focus to the suburbs.

Over the years, Sears had expanded outward, building up a large network of suburban department stores. Essentially, Sears followed their customers, first shipping to rural areas by catalogue, then building mixed-use plants in expanding cities, then adding suburban outlets.

Up through the 1980s, Sears was the largest retailer in the United States. But as the company spread out into suburbia, its urban developments began to fall into disuse. Driven by external economic conditions and internal restructuring, Sears started vacating (and in some cases selling) its various plants. Today, parts of the old Chicago hub have been torn down, but the iconic central tower and some other smaller structures have been preserved and, in some cases, reused.

Many other plants remained empty, in part because the sheer size of the structures made them challenging to reuse. The Minneapolis one, for instance, is the second-largest building (in terms of leasable space) in the state of Minnesota (behind the Mall of America).

Still, these old structures have some built-in advantages, including sturdy concrete, steel and masonry construction. They also have lots of natural light thanks to large peripheral windows, originally designed to illuminate offices but also well-suited to let daylight into dwellings. Thanks to rails-to-trails movements, locations along train tracks can be assets, too. Their industrial-meets-Deco aesthetic can also be a selling point. Over the decades, a number of cities have figured out ways to work with these features, turning old buildings to new purposes.

The Second Lives of Sears Plants

In Seattle, famous for its coffee, Starbucks proved a large enough occupant to fill out much of a particularly tall plant. This somewhat unusual example was built not by Sears but by a railroad company specifically to lure the mail-order giant out west.

Conveniently, too, the Starbucks reuse dovetails with a corporate approach of repurposing structures (rather than demolishing and building brand-specific architecture like many chains do).

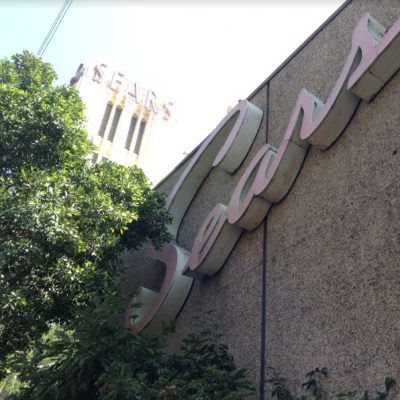

Boyle Heights (Los Angeles) Sears building contemporary images by Michelle Loeffler

In Los Angeles, the customer-facing, ground-floor Sears store remains open while much of the large building is shuttered. For years, though, a sign hung outside the structure offering its empty upper floors as a paid filming location, an apt use in the land of Hollywood.

Now, however, a new plan is in the works to renovate this plant in artsy Los Angeles with an array of mixed-use programming.

Spearheaded by developer Izek Shomof and designed by the firm Omgivning, the redeveloped structure will include live/work lofts, restaurants, pools, exhibition spaces and more.

Boston, meanwhile, set a precedent for mixed-use adaptations in mid-sized cities — its Landmark Center contains retail stores as well as a movie theater, sports complex and daycare center.

Ponce City Market in Atlanta and the Crosstown Concourse in Memphis likewise feature diversified programs with various stakeholders to help fill out these large old Sears plants. In Dallas, South Side on Lamar brought in a mixture of residential, retail and office tenants. In Oakland, a smaller Sears structure now houses much-needed residential units.

Of course, not all of these structures managed to adapt. Plants in Philadelphia and Kansas City were partially or entirely demolished before someone could come up with a better plan. Still, many of the ones that do remain have not just survived but thrived, becoming anchors for their neighborhoods and the cities around them.

Comments (12)

Share

If we had a big abandoned building like that here it could provide a lot of housing. Except that local regulations could be a hassle, not to mention asbestos abatement, and that a developer would want to make luxury apartments to max out his profits.

Luxury apartments and mixed-use retail in the former Sears distribution center in Atlanta. http://poncecitymarket.com/

Regarding Ponce City Market, “…feature diversified programs with various stakeholders to help fill out these large old Sears plants” is an understatement.

ULI 2016 Global Award for Excellence Winner

https://americas.uli.org/awards/ponce-city-market-2016-global-awards-excellence-finalist/

Now if only Atlanta natives could afford to live there (or the office & shop employees afford to even park there) maybe Atlanta would also think it’s excellent!

And that’s an overstatement, “Annie.”

And a $1,900 studio is an outrage, “George”, as are $90 parking passes for employees of a company that fronted the developers millions on the renovation.

Taco Cat!

Confirmed: Taco Cat is excellent.

Love that the Sydney version of this article features a paid advert trying to tempt a developer to buy and convert a Castle Hills showground. Very apt.

I used to work in the Sears Power House in Chicago! It’s now a school, but the architects kept some of the old equipment when they remodeled it. It was such an interesting space that one of my co-workers even had her wedding reception in our Great Hall area!

I know after the CampFire in Paradise CA, FEMA set up shop in the old Sears building in Chico. There was even talk about converting it to temporary housing. NOr that woudl be innovative.

The SEARS/Roebuck Catalog seemed to be the thing that launched and distilled this brand. And this of course has become antiquated. There’s only so much adapting print media can do, I think. Or maybe that’s not quite right. Like you point out, Scott, there is still a place for smaller, niche magazines. It would have been interesting to see, if decades ago, SEARS had found a way to modularize and personalize their catalog offerings to individual customers, as now seems to be commonplace. In other words, maybe what killed SEARS isn’t the Internet or not the Internet, but rather the fact that Amazon grew faster than retailers’ ability to leverage FB/social media/targeted ads to reach their customers in this suddenly all-important way.