In the Netherlands, about an hour and a half south of Amsterdam, there’s a city called Breda. Like many Dutch towns, it has cozy narrow streets, canals and plenty of bicycles. But there’s one historic building – right in the middle of town that really stands out from the rest.

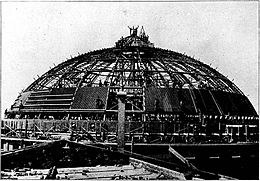

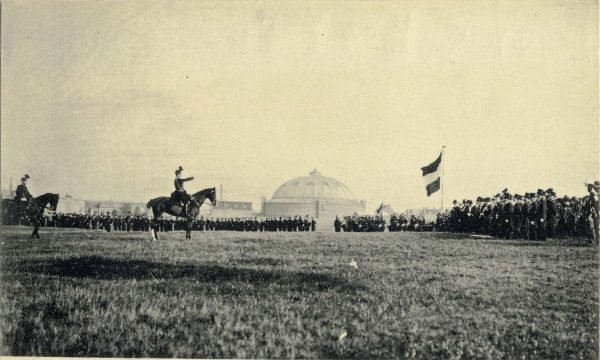

It’s a big, cylindrical structure, four stories tall, capped with this massive greenish-gray dome nearly a hundred twenty five feet up.

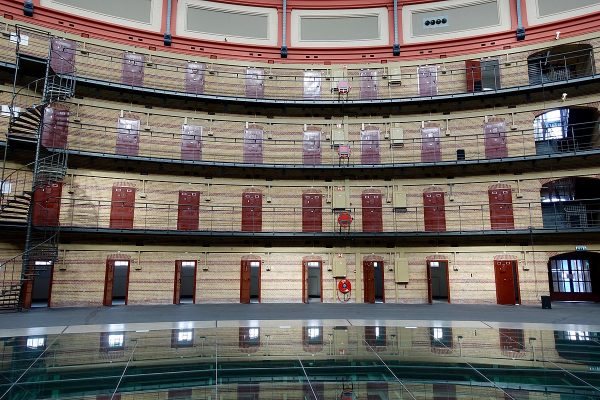

Inside the building, there’s a wide-open circular hall the size of half a football field with the sprawling dome overhead. Along the curved brick walls, there are hundreds of heavy orange doors spread out evenly across the four floors. And behind most of these doors are small rooms that were once prison cells. When this place was first built in 1886, it was a penitentiary. But not a typical one. This was a panopticon.

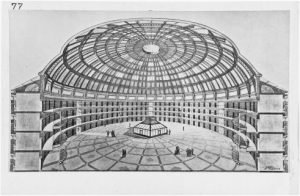

The “panopticon” might be the best known prison concept in the world. In the original design, all the cells are built around a central guard tower, designed to maintain order just by making prisoners believe that they are constantly being watched. The panopticon design is more than 200 years old, and it still shows up in popular culture, in productions like Star Wars and Guardians Of The Galaxy.

Over time, the panopticon has turned into something way bigger than just a blueprint for penitentiaries. It’s become the metaphor for the surveillance state. Philosopher Michel Foucault had probably the most popular take on the panopticon concept. He used it to warn society that what actually keeps all of us in check isn’t necessarily that someone is watching you. It’s just the feeling that someone might be watching you. But very few actual prisons were built around this idea.

As the prison system evolved, it became increasingly clear that grouping people together could be problematic, leading to all kinds of strife and helping to spread diseases. So in the 1800s, a new idea took hold: solitary confinement got really popular, which led to a major design change: the rise of “cellular prisons”. There wasn’t enough space in the existing prisons to retrofit them with individual cells, so they’d have to build something completely new. In 1870, the Dutch government turned to one of its most experienced architects to help realize this vision. His name was Johan Frederik Metzelaar.

The idea that we’re under constant surveillance seems familiar to many of us now. We just kind of accept that there are cameras and CCTV everywhere, and that we’re always being tracked on our computers at work. But back in the late 1700s, a design for watching so many people all at once in a way that Bentham hoped would be productive. He believed that isolating inmates was key to a functioning panopticon prison. Individual cells kept prisoners from fighting, or conspiring to escape. It was easier for guards to keep an eye on inmates who were alone, making sure they did nothing but repent for their crimes. For Jeremy Bentham, isolation and centralized surveillance worked hand in hand. He said that inside a well-watched, cellular panopticon, jailors would see the inmates as “a multitude, though not a crowd.” And the prisoners would be, he wrote, “solitary and sequestered individuals.”

The idea that we’re under constant surveillance seems familiar to many of us now. We just kind of accept that there are cameras and CCTV everywhere, and that we’re always being tracked on our computers at work. But back in the late 1700s, a design for watching so many people all at once in a way that Bentham hoped would be productive. He believed that isolating inmates was key to a functioning panopticon prison. Individual cells kept prisoners from fighting, or conspiring to escape. It was easier for guards to keep an eye on inmates who were alone, making sure they did nothing but repent for their crimes. For Jeremy Bentham, isolation and centralized surveillance worked hand in hand. He said that inside a well-watched, cellular panopticon, jailors would see the inmates as “a multitude, though not a crowd.” And the prisoners would be, he wrote, “solitary and sequestered individuals.”

Several decades later, Dutch architect Johan Metzelaar picked up Bentham’s ideas. He was drawn to the panopticon because it solved several practical concerns. One of the things Metzelaar liked most was the emphasis on individual cells – an ideal design for solitary confinement. Since the cells were arranged in circles, inmates would have minimal interaction. Also, the panopticon was a cost-saving design. It would require less construction than the typical prison, because there’d be no need for a separate church. The priest could just deliver his sermons from a central structure, without the inmates ever leaving their cells. Plus, the prison was designed so it would take fewer people to run it. You wouldn’t need as many guards because just the specter of constant surveillance would do a lot to maintain order.

Several decades later, Dutch architect Johan Metzelaar picked up Bentham’s ideas. He was drawn to the panopticon because it solved several practical concerns. One of the things Metzelaar liked most was the emphasis on individual cells – an ideal design for solitary confinement. Since the cells were arranged in circles, inmates would have minimal interaction. Also, the panopticon was a cost-saving design. It would require less construction than the typical prison, because there’d be no need for a separate church. The priest could just deliver his sermons from a central structure, without the inmates ever leaving their cells. Plus, the prison was designed so it would take fewer people to run it. You wouldn’t need as many guards because just the specter of constant surveillance would do a lot to maintain order.

The Dutch believed that this form of punishment was the best way to make criminals more fit for a god-fearing society. The Netherlands enthusiastically used solitary confinement to both discipline criminals and prevent crime. But by the early 1930s — about four decades after the Breda dome prison first opened — people were realizing that this whole theory of rehabilitation was nonsense. The expensive, groundbreaking panopticon experiment in the Netherlands was actually a tortuous disaster. Isolation wasn’t rehabilitating anyone. Instead, it was causing severe mental illness and death among prisoners. Although this was a panopticon building, the main issue wasn’t surveillance. It was solitary confinement.

The Dutch believed that this form of punishment was the best way to make criminals more fit for a god-fearing society. The Netherlands enthusiastically used solitary confinement to both discipline criminals and prevent crime. But by the early 1930s — about four decades after the Breda dome prison first opened — people were realizing that this whole theory of rehabilitation was nonsense. The expensive, groundbreaking panopticon experiment in the Netherlands was actually a tortuous disaster. Isolation wasn’t rehabilitating anyone. Instead, it was causing severe mental illness and death among prisoners. Although this was a panopticon building, the main issue wasn’t surveillance. It was solitary confinement.

Then, when the Nazis occupied the Netherlands in 1940, they turned many Dutch penitentiaries into prisons for those who resisted the occupation. State officials, judges, and lawmakers were all put behind bars. Obviously a pretty unusual situation. But those Dutch elite got to experience firsthand the sheer awfulness of prison. After the war, Dutch leaders once again called for a transformation of the nation’s prisons. This time, criminal law reformers pushed for alternatives to incarceration. he Dutch were also again rewriting their laws to emphasize rehabilitation. This time, not by trying out a new and untested design theory, but instead by reducing the number of penitentiaries around the country. Starting in the early 1950s, the Dutch also began decreasing their use of solitary confinement. Inside of Breda, they got rid of strict isolation. They built spaces where inmates could interact, including a library, a gym and several workshops.

Today, the closed prison is home to Ukrainian refugees. But the panopticon building has preserved some questionable elements from the past. There are still bars on the windows. And the doors to the rooms where the refugees sleep cannot be locked from inside. There’s a dining hall in the center. Sun pours in through the dome skylights and falls on cozy armchairs. There’s a gym in the basement where refugees get together for yoga lessons and volleyball. Despite the cell doors and the old iron bars and gates, Breda’s panopticon has finally managed to become a truly humane place. But only after it stopped being a prison.

Leave a Comment

Share