Flag semaphore tends to conjure images of modern-day military messaging — Navy personnel, for instance, waving bright squares of signal fabric on ships at sea. Historically, semaphore gained particular wartime prominence during the French Revolution, when it facilitated fast official communication across the nation. But semaphore has also become embedded in an iconic anti-war symbol, created by a British designer for a particular cause before taking the world by storm.

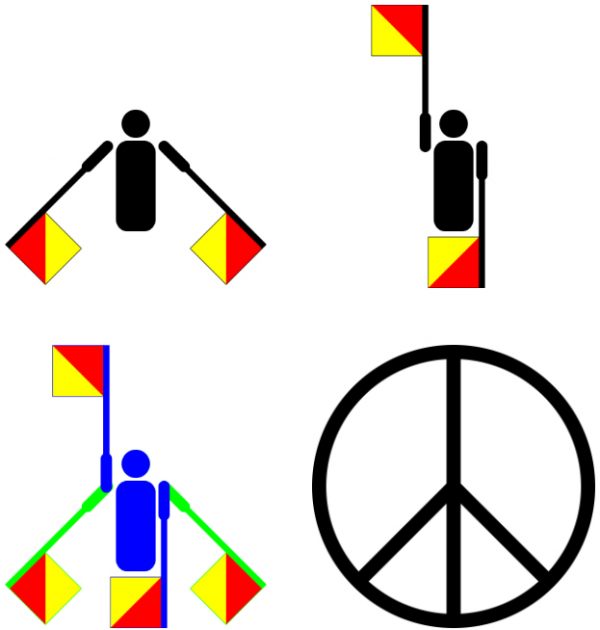

Born in England during the first year of World War I, Gerald Holtom would grow up to become a conscientious objector in World War II. After graduating from the Royal College of Art, he took a job at the Ministry of Education. Then, in 1958, he designed something on the side — a nuclear disarmament logo for a protest march organized by the newly-formed Direct Action Committee against Nuclear War (DAC), supported by the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND).

The marchers would carry 500 copies of the new symbol along their 50-mile journey from London’s Trafalgar Square to Britain’s Atomic Weapons Research Establishment. In the first large-scale anti-nuclear march of its kind, protesters united under this symbol. They hoisted it on banners and placards but also wore it on their persons — a reminder of each individual’s responsibility to stand up against war.

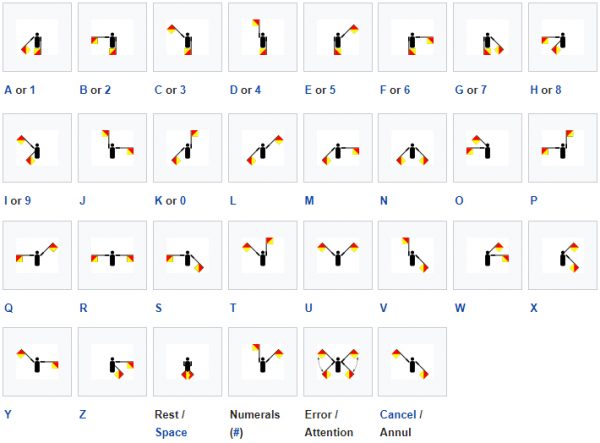

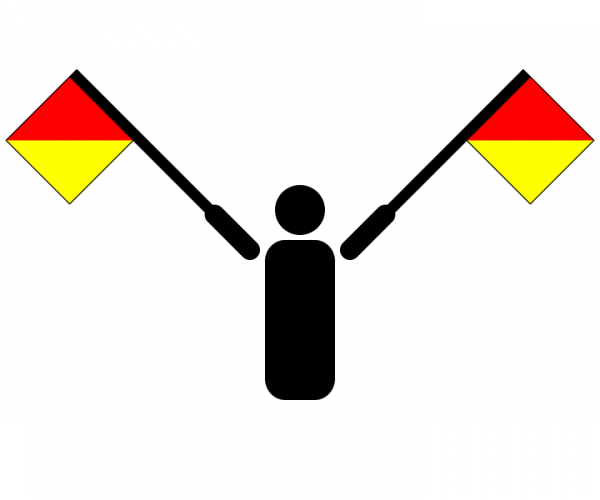

In terms of flag semaphore, this new anti-war symbol could be read as a combination of the letters, too: ‘N’ and ‘D’ standing for “nuclear” and “disarmament,” made up of vertical line for the D and two downward-angled lines for the N. These overlaid signs are set within a circle to form a simple but memorable black-and-white graphic. Implicit in the symbol is an abstract individual standing within the ring and holding up the “flags” to signal their stance against nuclear weapons.

According to Andrew Rigby, Emeritus Professor of Peace Studies at Coventry University in the United Kingdom, this symbol wasn’t Holtom’s first attempt. He considered a dove, but that had been appropriated by the Stalin regime to legitimize their work on the hydrogen bomb. He also thought about the Christian cross, but realized it could be associated with crusaders (and, more recently: the Western nation that dropped nuclear weapons, devastating Japan). Holtom wanted to create something that could be universally adopted, without the symbolic baggage of fraught iconography.

So, in a state of “deep despair,” Holtom later wrote, “I drew myself: the representative of an individual in despair, with hands … outstretched outwards and downwards …. I formalized the drawing into a line and put a circle round it. It was ridiculous at first and such a puny thing.” It was to him as much a gesture of desperation as it was a work of design.

Even then, he wasn’t sure it was the right solution, but he drew it out on a piece of paper then pinned it on his jacket and forgot about it. When a woman at the post office then asked him about it, he recalled, “I looked down in some surprise and saw the ND symbol pinned on my lapel. I felt rather strange and uneasy wearing a badge. ‘Oh, that is the new peace symbol,’ I said. ‘How interesting, are there many of them?’ ‘No, only one, but I expect there will be quite a lot before long.'”

Early versions produced and circulated for the CND look a bit more like abstracted persons — approaching the circle, the lines widen, suggesting a head toward the top and forward-leaning arms. They were also made of clay and handed out with a dark message: in case of a nuclear war, these may be the only artifacts that outlast the person wearing them.

Early versions produced and circulated for the CND look a bit more like abstracted persons — approaching the circle, the lines widen, suggesting a head toward the top and forward-leaning arms. They were also made of clay and handed out with a dark message: in case of a nuclear war, these may be the only artifacts that outlast the person wearing them.

The CND continued to use the design in the U.K., but the symbol also made its way around the world, and it came to symbolize peace more broadly. In the United States, a pacifist protester shined a spotlight on the symbol in 1958, hoisting it up on a small boat he piloted into a nuclear test zone. A few years later, a delegate from America’s Student Peace Union (SPU) returned from a trip to Britain and convinced his group to adopt the symbol and distribute it on college campuses.

Absent copyright, the symbol’s usage has continued to expand over time. It has since been described as “probably the most powerful, memorable and adaptable image ever designed for a secular cause.”

Holtom, though, came to question the negativity of the implied figure in his graphic, which also looked like the runic symbol for “death” (an inversion of the “life” rune). But he also realized something: if the symbol were inverted, it could look like a “tree of life,” representing hope and optimism — and the upward-reaching arms could signify the letter U in semaphore. Coupled with the D, this flipped figure could stand for “unilateral disarmament,” too, Holtom’s ultimate dream.

Comments (1)

Share

Maybe “universal disarmament“ would be a better alternative than “unilateral disarmament”?