Dotting the hillsides of Europe, the remnants of a vast long-distance communications network look a bit like anachronistic cell towers. Some of these infrastructural remains date all the way back to the French Revolution, a period of regional turmoil during which a novel approach to semaphore (visual messaging) played a pivotal role.

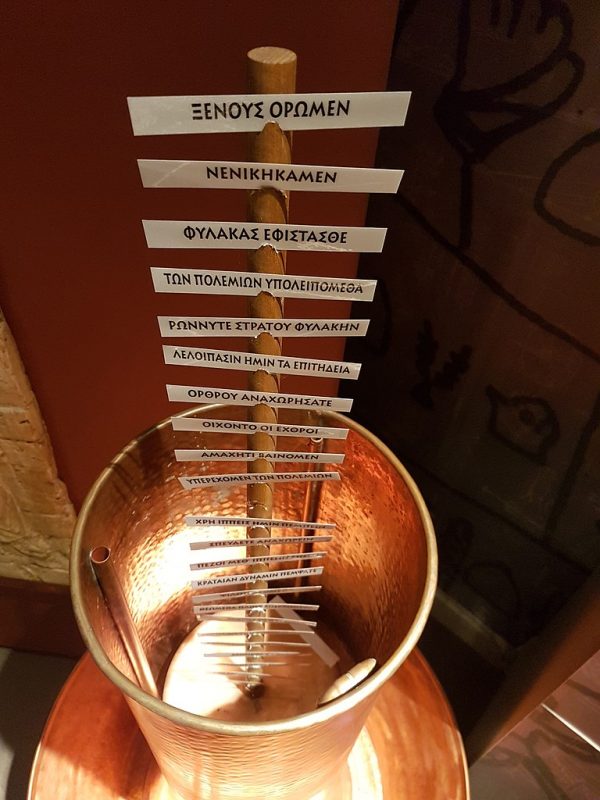

Smoke signals, beacons, reflected lights, homing pigeons and other lower-tech ways of communicating across distances have, of course, been used since ancient times. Some, like the “hydraulic telegraph” of ancient Greece (shown below), were quite sophisticated, too — that particular system employed signal fires to cue operators who would turn on spigots (resulting water levels indicated different messages).

In the modern era, the electric telegraph (then later: the telephone and internet) came along and largely replaced these vintage solutions — but the term “telegraph” itself (from Greek roots, meaning “distance writing”) actually predates that world-changing technology.

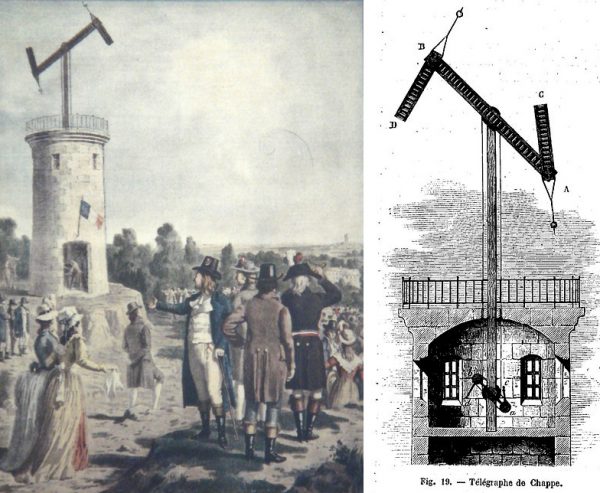

“Telegraph” was coined back in the 1790s by Claude Chappe, a French inventor who designed what would become a national semaphore network (Greek, from sêma for “sign” and phorós for “carrying”). Arguably the first large-scale, high-speed communications network in the world, this system was lightning fast by standards of the time.

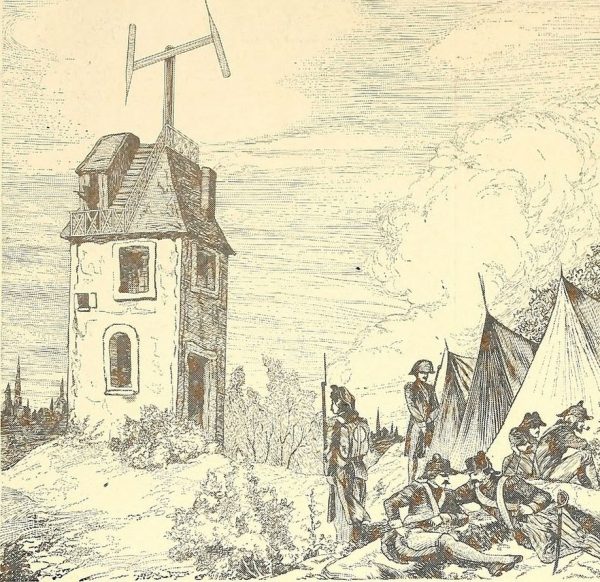

It was a dark decade for France, a country at war, surrounded by military forces of the Netherlands, Britain, Prussia, Austria, and Spain. Internally, the cities of Marseille and Lyon were in open revolt. The besieged government needed to relay messages quickly, and Chappe had a solution: a series of towers spaced up to 20 miles apart, each mounted with a set of wood posts that could be spun to create nearly 200 symbols. Tower operators would position these to send messages to watchers at other towers, who would then relay them further. Many of the messages were encrypted, to be decoded at the end of the line.

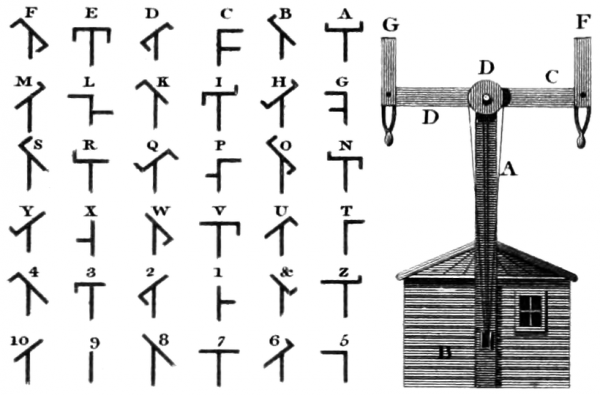

The system evolved through experimentation and iteration (a few test towers were even destroyed by angry Parisian mobs). The finalized devices consisted of two six-foot wooden arms connected by a crossbar — the positions of all three together could be used to indicate a letter. Numerous possible combinations also allowed for words and phrases to be encoded in addition to the basic alphabet. Designed to be robust but also easy to use, the machines were operated with handles, which were in turn tied into a system of counterweights. Communication was broken down into a set of three basic steps:

- Setup: Indicator arms get turned to align with the crossbar, forming a non-symbol, before the bar is moved into position for the symbol.

- Transmission: Indicator arms are positioned for the current symbol — operator waits for the downline station to copy it.

- Completion: Crossbar is turned to a vertical or horizontal position, indicating the end of a cycle.

Signals could be sent at a rate of roughly three per minute, and travel over 100 miles in under ten minutes, far faster than messages communicated by horse or other conventional options of the era. The system had limitations, though — it required periodic stations, so it was hard to operate across large stretches of water (in the absence of islands), and it was subject to visibility interruptions depending on the weather. Nonetheless, it was considered a huge success.

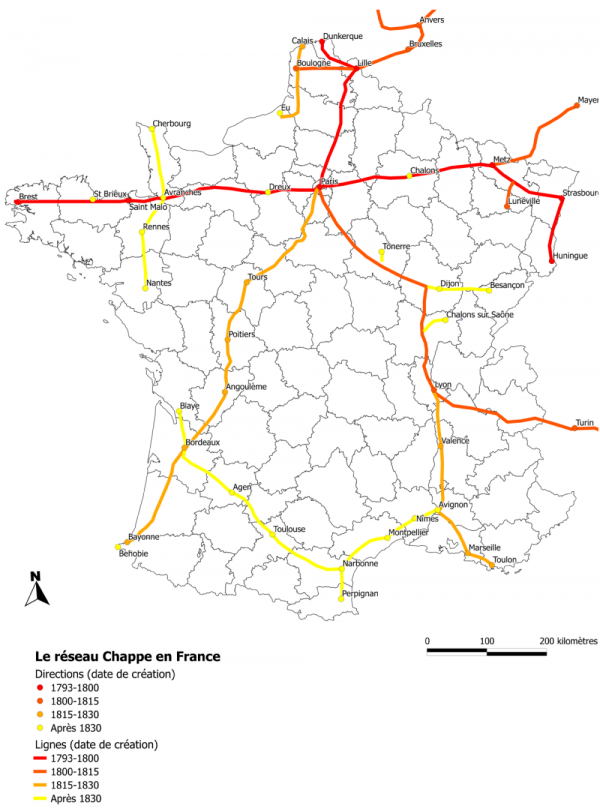

The network grew and spread across France — at its peak, more than 500 semaphore stations spanned over 3,000 miles, connecting major cities with Paris as a central node.

The technology was also picked up by other European countries, including Sweden and the U.K. Some adapted the concept to improve communication speed as well. The United States and Canada also developed variants of point-to-point signal communication.

Even with the advent of the Samuel Morse’s electrical telegraph in the early 1800s, a number of semaphore networks continued to operate in Europe — the last station in France was decommissioned in 1852, and Sweden continued to use theirs up through 1880.

Comments (1)

Share

A semaphore system operated at the other end of the earth, in Tasmania until 1877. It went from Mount Nelson, near Hobart to the penal settlement in Port Arthur. http://www.utas.edu.au/library/companion_to_tasmanian_history/S/Semaphore.htm