According to British railway lore, the “slip coach” was born when a rail official was riding in a train car that came an unexpected stop. The rest of the express train kept going while his carriage glided to a gentle halt in front of a midway station. As the story goes, the coupling chain broke in transit, so the guard on the slipped car used his handbrake to slow and guide it carefully to a halt alongside the platform. Fascinated by the accident, the official wondered: could we do this on purpose? Thus, in the mid-1800s, train operators began detaching passenger cars in motion, sending them into stations without motive power of their own.

The more likely actual origin story is a little less sudden and dramatic, but nonetheless fraught. Before slip cars, there were reckless rail car detachments — a locomotive might simply slow down a bit to provide some give while an engineer decoupled rear cars on the fly.

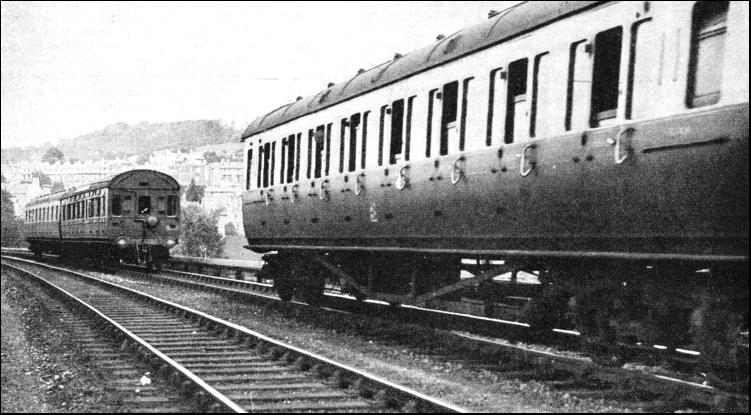

Once a slip coupling was developed, there was theoretically no limit to the number of cars that could be slipped or how many times it could be done along a route. An express train between London and Glasgow could, for instance, drop a few cars off in one smaller town or city along the way, then a few others in another (as long as there was a guard manning a set of brakes in the lead car slipped at each stop). The slipped cars could then open up to let riders off, or be attached to another train, routing them along without people needing to transfer.

Passengers boarding a typical car of this kind could expect to be locked in for the duration of the journey, largely for their own safety. Unable to access restaurant cars, however, some customers complained, and corridor-accessible variants were developed. But these led to other concerns — for instance, what if a car was slipped while someone was away from their car or between cars? A lot depended on the guard, ultimately, who had to time things and watch signal lights on the car ahead to cue his release. The main train operator also had to be careful — in at least one case, accidentally slowing down post-slip resulted in a collision with a detached car behind running into the main train.

By 1914, close to 100 cars were being slipped each day. At its peak, the British rail network had as many as 200 working slip cars. But while the system was used for close to a century in Britain, it did have its costs and drawbacks. Each slipped car set required its own guard, as well as people to reattach the cars, adding to personnel needs. And while cars could be detached on the move, they couldn’t be as easily reattached.

As trains grew faster, the prospect of disconnecting cars at speed also became increasingly fraught with potential danger. In the end, due to costs and other concerns, the last slip journey took place in 1960 (a historic final trip that was documented in the video above).

The basic idea of dividing cars continued on, though. In some cases, trains halt to detach cars that are then reconnected to a new engine. In others, multiple locomotives are connected for a stretch, then separate at a stop before continuing under their own power. Such divided-train systems have made their way across Europe and to the United States.

But while modularity persisted, the most exciting (and dangerous) element was dropped from the mix — jettisoning cars in motion.

Leave a Comment

Share