Earlier this year, the city of New York closed off several blocks around the Manhattan Criminal Courthouse. Instead of early morning commuters, the sidewalks around the building were flooded with reporters, photographers, and camera people. They were there to capture the arraignment of former president Donald Trump.

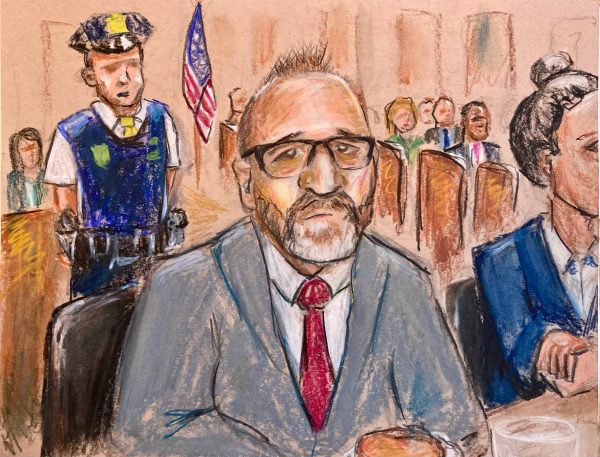

Members of the media were so desperate to get a good shot that they camped out overnight outside the courthouse. And it’s because people all over the world demanded an immediate visual record of this historic moment. Viewers were hoping to watch Trump’s perp walk into the courtroom, or see his mugshot, or see a video of him being read his felony charges. Instead, the image that was everywhere from the Guardian, to the Washington Post, even on the cover of the New Yorker … was a hand-drawn courtroom sketch.

The sketch was done by a New York-based artist named Jane Rosenberg. Somehow Rosenberg managed to perfectly encapsulate his hair with just a few messy strokes of an oil pastel. His face was frozen in a deep cutting scowl. Courtroom sketches have a different flavor than photographs — more like a memory of a moment than a captured one.

But perhaps the most fascinating thing about courtroom illustration is that it still exists. Because you can’t really talk about courtroom illustration without addressing the elephant not in the room: photos. Next to a camera, pastel on paper feels like an archaic way of documenting some of the most important legal events of our time. Cameras are faster, easier, and more accurate than a human illustrator, but courtroom artists are still constantly used in high profile cases.

Courts of Public Opinion

The answer to how courtroom artists have managed to survive the camera for so long, is wrapped up in a decades-long tug of war between transparency and integrity in the courts. It’s a century-long battle that centers around the question of whether it’s even possible to observe the justice system without changing the course of justice.

In 1932, the now-infamous case of the Lindenberg baby kidnapping hit the news and caught the world’s attention. In Hopewell, New Jersey, someone came into a second floor nursery, climbed up on the ladder, went into the the baby’s nursery and took him away that night.

The kidnapper left a note demanding $50,000 in ransom. Sadly, the Lindberghs’ son was never recovered alive. The child’s body was discovered less than five miles from the Lindbergh home and police later charged a German-born immigrant named Bruno Richard Hauptmann with the murder. And then on January 2nd, 1935, the crime of the century gave way to the trial of the century.

Everyone wanted a taste of this story, and the press was more than happy to provide that access. About 700 reporters, photographers, and camera operators descended upon New Jersey where Hauptmann was standing trial. At this time, motion picture cameras (which had only recently entered the courtroom) were these clunky masses of metal that took up a lot of space and made a whirring noise and even still photographers weren’t subtle — large with popping lights and so on.

The judge was concerned about all the distraction photographers and camera reels would have, so he strictly forbade any photography or motion picture capture during the course trial. Camera operators were only to capture the moments before court was in session, and after. But during a particularly heated and key exchange, newsreel operators defied the ban, capturing critical moments of the trial.

Shortly after Hauptmann’s questioning, the newsreel footage of this interrogation spread quickly, playing to packed movie houses around New York City. Eager patrons lined up around the block to watch the bombastic courtroom scene. The public saw it, and got riled up.

When the the jury finally goes into deliberate the case there are packs of people around the courthouse. and the mob starts to get a little unruly as the the jury deliberation goes on for a few hours longer than most people thought it should have gone on. They started screaming, “Kill the German, kill Hauptmann.” The jury returned its verdict. Bruno Hauptmann was found guilty and was sentenced to death by electric chair.

Although it’s unclear how much, or even if, the leaked footage had any impact on the verdict, the world was appalled by the carnival-like atmosphere that the press had created during the trial. Many in the judicial system believed that the presence of photographers, newsreels, and other journalists made a complete mockery of the court.

There were also arguments that cameras didn’t just tarnish the solemnity of the courtroom process, they could possibly interfere with our constitutional right to a fair trial. After all, how could a trial be fair with all this outside passion and influence brought into the courtroom?

So in direct response to the Hauptmann trial, the American Bar Association adopted something called Canon 35. This condemned the use of photography, motion picture, and radio recording within the confines of the courtroom. It wasn’t a law, per se, but a code of ethics that cautioned against recording technology in the trial process. And many state courts adopted that policy.

In 1946, The US government went even further and expressly banned all cameras from federal courts, making way for illustrators.

Camera-Free Courts

The rise of the courtroom artist was also driven, in part, by television. By the 1960s television had become a staple in most American households. Nightly TV news programs were evolving to cover the big events of the day, and there was more demand than ever to see inside high profile court cases. But with no cameras allowed in, the courtroom was a visual black box. So television networks found a loophole that would follow the spirit of Canon 35 while still letting the public take a peek into proceedings: courtroom illustrators.

One of the first people to sketch a trial for television was a man named Howard Brodie. Brodie was hired by The CBS Evening News in 1964 to create the visuals for the trial of Jack Ruby, the man convicted of killing Lee Harvey Oswald. Other networks followed suit and began teaming up with artists in the courtroom. Brodie’s work turned courtroom illustration into a real job and broke open the profession for a number of other aspiring artists. Unlike a photographer holding up a camera, a sketch artist has the ability to quietly blend into the room. No one was worried that that trial participants would become distracted, or that witnesses would feel too intimidated to testify, or that jurors would be fearful that their privacy would be at stake.

The courtroom is notoriously a place where people experience the worst days of their lives. Illustrations capture elements of this in still frames, almost deceptively motionless. But not everyone is satisfied with the curated calm of a courtroom sketch. Proponents of cameras in courtrooms think that the public shouldn’t have to rely on being told what was happening in a court of law, they should be able to see it in action for themselves.

From the beginning, Canon 35 was more of a strongly worded suggestion than a law. By the 1960s, three decades later, new sensibilities started to erode the wall erected against cameras in the courtroom. Those pushing for cameras argued that they offered increased oversight of the justice system. Meanwhile, television and photojournalists were making the case that with their quieter, modern camera technology, their presence was now just as unobtrusive as the discreet courtroom artist. Far from being intimidated, witnesses and lawyers would barely notice the cameras were there.

Media advocates also believed that televising trials offered a great educational resource for people who couldn’t physically be in a courtroom but wanted to learn more about the legal system. So Beginning in the 1970s, different state courts began ignoring the canon and experimenting with broadcast coverage of judicial proceedings. By the 1990s most states allowed some sort of camera access.

And the experiments, for the most part, went well! Cameras became so common in the courtrooms that by 1991 there was a whole television network dedicated to it called Court TV.

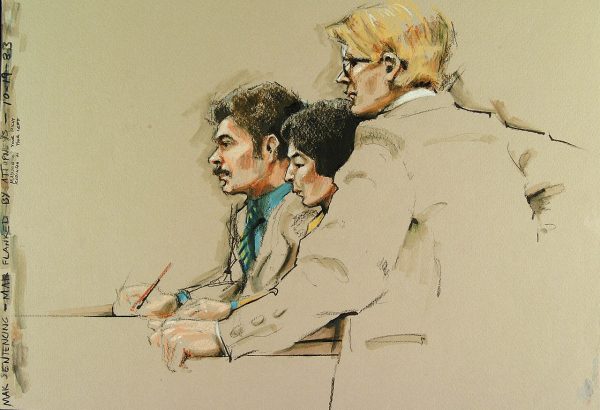

Soon, even federal courts, which had a much more stringent ban on cameras since the 1940s, also began testing the waters and televising their trials. Huge high profile cases like the Menendez Brothers and Jeffrey Dahmer were all aired gavel to gavel on television. With video cameras becoming more and more the norm in the 1990s, some courtroom artists were worried that their jobs were in danger. What was the point of a network hiring an illustrator when every single trial moment was instantaneously documented live on television?

And then the O.J. Simpson case happened. Beginning 1995, the city of Los Angeles began the grueling 8 and a half month criminal trial of OJ Simpson. The presiding Judge, Judge Lance Ito seemed absolutely incapable of managing courtroom antics. And most observers blamed the bloated media presence.

For media transparency advocates who had argued for decades that camera technology wasn’t disruptive, that witnesses wouldn’t be intimidated by the camera lens, that lawyers weren’t going to put on a dog and pony show, that the integrity of the justice system wouldn’t be compromised: the Simpson trial seemed to prove the exact opposite.

Comedians made a mockery out of a double murder trial for eight straight months. Jay Leno even featured a chorus line of Judge Ito impersonators performing choreographed jazz numbers every night. State and federal judges all over the country saw this unfurling live on television and took it as an example of what could happen to them if they brought cameras into their courtrooms.

So once again the snake rounded back on its own tail as judges across the nation unceremoniously banished recording technology from their courtrooms. Accordingly, this circularity granted a stay of execution for sketch artists. Despite years of push and pull… and push, cameras are still kept in a legal gray area. They are still banned in all federal courts, and in most state and criminal courts it varies from case to case. And although today we’ve developed much more discreet ways to record a trial, like audio or video streaming, many judges are still hesitant to bring any sort of recording technology into the courtroom.

When the justice system already feels so fragile and there is so much on the line for the defendant and the victims of a case … when someone’s life could be on the line … one might wonder: why risk introducing any element, no matter how small, that could negatively impact what happens in a court of law?

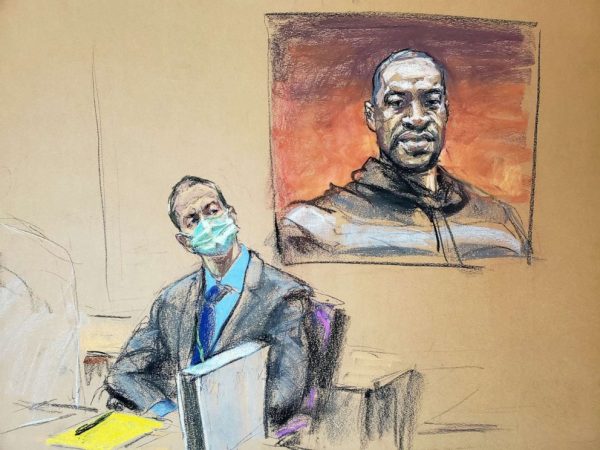

In March of 2021, the trial of Derek Chauvin, the police officer who murdered George Floyd began in Minneapolis, Minnesota. It was a case that had international attention, and for Minnesota — which had become the epicenter of the racial justice movements around the world — the burden was especially heavy.

At the time of the trial, Minnesota actually had very stringent rules regarding electronic media in criminal courtrooms. Essentially, everyone involved from the defendants, to the prosecution had to give permission to allow recording during the trial process. If anyone objected, that was the end of it. But Judge Cahill decided that the entirety of the trial needed to stream live for the world to see.

The judge set a lot of ground rules for the broadcast in order to mitigate problems before they happened. Jurors were not allowed to be recorded, there were restrictions on which witnesses could be filmed, and the movement of the cameras was limited. But– in a break with history– the broadcast of the trial went off nearly hitch free. Courtroom illustrators, of course, were welcome to ply their trade as well.

There were no antics, no one reported being intimidated, and after this experience, the lead prosecutor who had originally opposed the broadcast changed his view entirely and is now a supporter of cameras in the court. In March of 2023, the Minnesota Supreme Court ruled to expand camera access in state criminal trials. Starting in 2024, permission from both the defense and prosecution will no longer be required to broadcast courtroom proceedings.

Earlier this year Senators Grassley and Durbin introduced a bipartisan bill that would bring cameras in the Supreme Court for the first time. The Court has never really been known for being super chill about things like change, or technology, or transparency. and former Justice Souter once famously said, “the day you see a camera come into our courtroom, it’s going to roll over my dead body,” so whether that bill would ever actually pass is hard to say. At least for now, courtroom artists are still safe.

You can check out Ashley Feinberg’s Slate investigation into the Supreme Court gaffe from the coda here.

Leave a Comment

Share