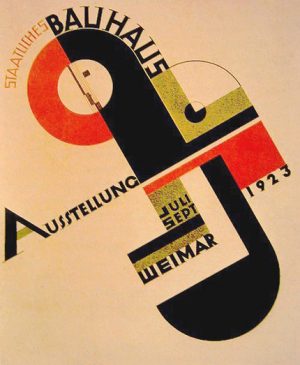

Founded by architect Walter Gropius in 1919, the Bauhaus school in Germany would go on to shape modern architecture, art, and design for decades to come. The school sought to combine design and industrialization, creating functional things that could be mass-produced for the betterment of society. It was a nexus of creativity in the early 20th century. Most now-famous designers and artists who were in Europe during the 1920s and ’30s spent time at the Bauhaus.

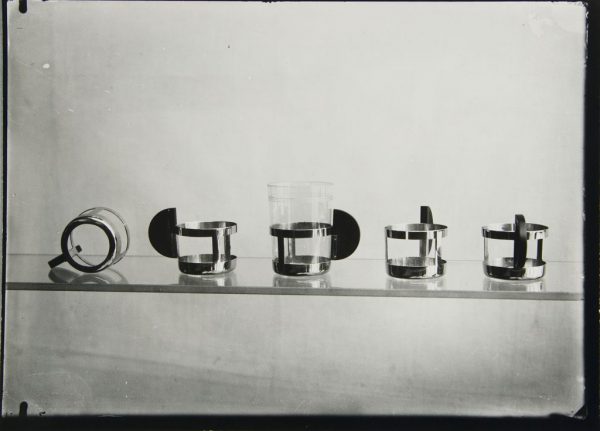

The popularity and influence of the Bauhaus beyond Germany, however, owes a great deal to a lesser-known photographer: Lucia Moholy. Her photographs are some of the finest documents of the Bauhaus’s architecture and its products. Moreover, the composition of Moholy’s photos—full of striking asymmetry, and stark contrasts, and seriality—draw on the very ideas that the Bauhaus espoused.

Moholy’s photographs of the Bauhaus are both representations of the school, and works of art in their own right.

Building the Bauhaus

Lucia Moholy first came to the Bauhaus in 1923 when her husband, the artist László Moholy-Nagy, was hired to teach at the school. Like many people married to faculty, Moholy sought to make herself useful to the Bauhaus.

She leaned on her training in photography to become a documentarian for the Bauhaus, taking pictures of the buildings where they worked, the things they made, and the people who made them.

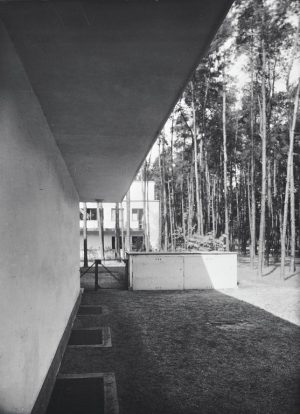

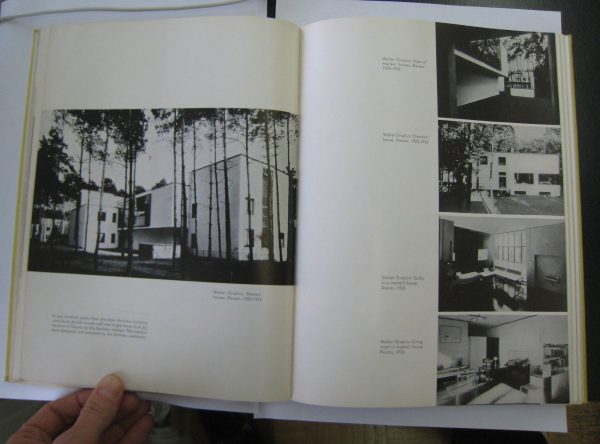

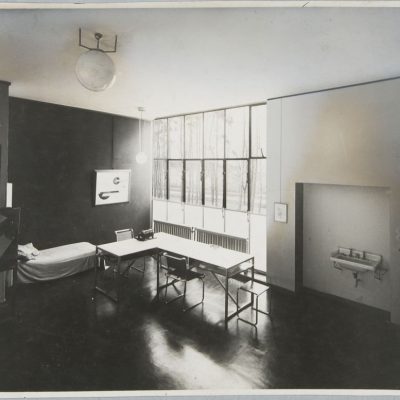

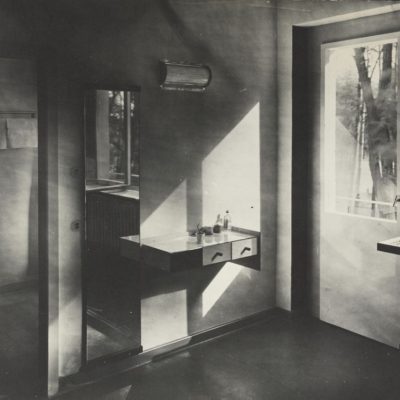

The buildings designed by Bauhaus founder Walter Gropius for its campus in Dessau would become a major theme of Moholy’s work. She photographed the school’s workshops, the dormitories, and the masters’ houses.

The photographs shot by Moholy, much like the architecture designed by Gropius, embodied a balance of clarity, simplicity and asymmetry. Her representations are utilitarian, documenting the world as it is, but they are also beautiful, reveling in clean lines and stark contrasts.

Moholy would ultimately take hundreds photographs, which would go on to have a tremendous impact on the built world. Yet as she took them, she never could have guessed the impact those photos would have on her own life — or that she would spend years fighting to regain control of them.

A World at War

The Bauhaus (literally: “build house”) was built on aspirations to help lift society out of the wreckage of World War I into a new world of beauty and rationalism. Yet as the Nazis rose to power in advance of World War II, the school came under threat.

Amidst the turbulence of the Nazi Party’s rise to power, Lucia Moholy and her husband László Moholy-Nagy had separated. By 1933, Moholy had begun dating a Communist Party member of parliament. One day he was arrested in Moholy’s apartment while she was out. Moholy was warned not to return home, or risk arrest also.

Moholy fled to Prague temporarily to stay with family, and then made her way through Switzerland, and then Austria, and then Paris, eventually settling in London. Moholy had left behind everything she owned—including her huge collection of five-by-seven-inch glass negatives of the photos she had taken at the Bauhaus.

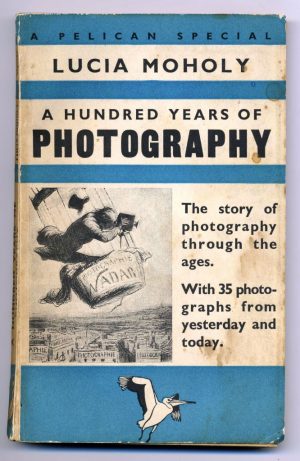

Moholy weathered out the war in England. While there, she worked as a portrait photographer for British high society, and also published A Hundred Years of Photography, a book about the medium’s history. In many ways, she moved on from thinking about the Bauhaus—at least for a while.

The Bauhaus in Diaspora

Following World War II, there was a surge of interest in the Bauhaus. Their ideas about rationalism and modernism had caught on among postwar architects and designers.

In the mid-1940s, Moholy came across a copy of a 1938 Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) catalog that had made its way from New York to London. The catalog included an array of photographs from the Bauhaus era, including some of Moholy’s. But to her surprise, the captions didn’t credit her as the photographer.

Over time, more and more books and articles about the Bauhaus were getting published, and Moholy’s photographs kept getting circulated—but generally without her name attached.

Many of the photographs that Moholy saw getting published were too high-quality to be reproductions of existing prints. They had to have been made from the large-scale negatives she left in Germany. As Moholy received ever-more requests to give lectures on the Bauhaus, Moholy began trying to track down these negatives.

A friend told Moholy that during the war, the negatives had been put into the care of Walter Gropius. When Gropius left Germany, he apparently had sufficient time to pack and ship the fragile glass negatives, sending them to his new home in Cambridge, Massachusetts, to where he was emigrating.

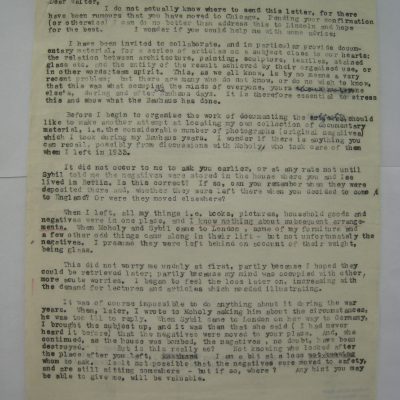

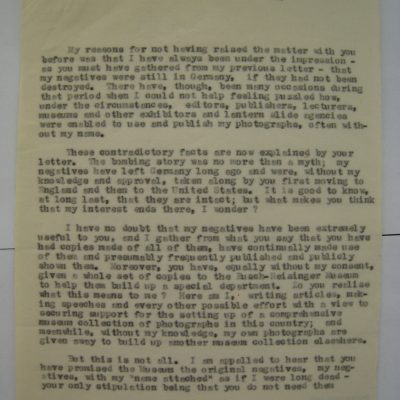

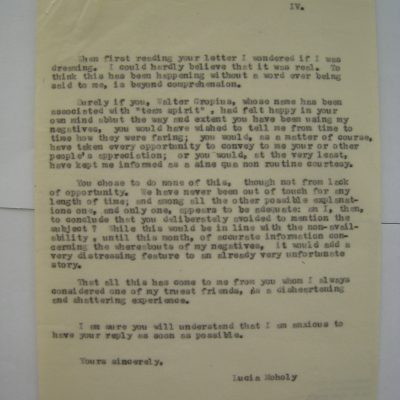

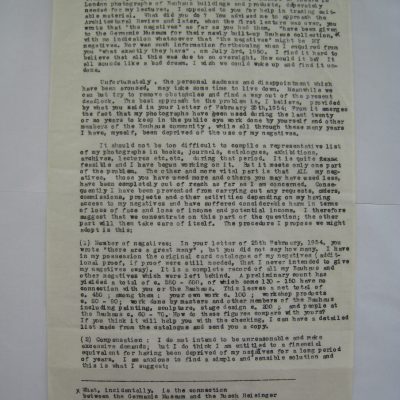

Moholy repeatedly asked Gropius for the negatives. Thus began a correspondence that would escalate over months and years (excerpts):

Moholy: These negatives are irreplaceable documents which could be extremely useful, now more than ever.

Gropius: Long years ago in Berlin, you gave all these negatives to me. You will imagine that these photographs are extremely useful to me and that I have continuously made use of them; so I hope you will not deprive me of them.

Moholy: Surely you did not expect me to delay my departure in order to draw up a formal contract stipulating date and conditions of return? No formal agreement could have carried more weight than our friendship. It is this friendship I have always relied on, and which, also, I am now invoking.

When invoking friendship didn’t work, Moholy hired a lawyer who wrote to Gropius that his holding onto these negatives was akin to firefighter saving a house—and then claiming ownership of all the objects he saved from inside of it.

Copies, Rights, & Realities

Who owns an image of a building? Intellectual property law on photography has evolved over the years, and still varies by country. Still, some rules of thumb that apply in many cases and places.

Generally, if someone takes a picture of a copyrighted two-dimensional object (like a painting) , the photographer has no claim to the ownership of that image. However, if one photographs a three-dimensional object, especially one viewable in public space (like a building), the photographer is clearly making decisions about composition, position, angle, lighting, framing—therefore, the photographer in this case is generally afforded more legal claim to the photograph’s copyright (though various caveats do apply).

In any case, right or wrong, Gropius kept making prints from Moholy’s negatives, kept publishing them, kept circulating them, and kept telling the story of the Bauhaus through her camerawork.

Photography & Legacy

In many ways, architecture is understood and consumed through photography. For the most part, we don’t see the most iconic buildings in person—we see pictures. This turned out to be especially true of the Bauhaus buildings, because after the start of the Cold War, the West’s access to the Bauhaus campus was cut off by the Iron Curtain. Even in East Germany it was incredibly difficult to photograph the Dessau campus—photography was banned there outright from 1950 until 1980. After reunification, the buildings were altered slightly. And so, to this day, scholars say that Moholy’s photographs are some of the best representations we have of the Bauhaus.

After years of legal disputes, Moholy finally succeeded in getting nearly 300 of her negatives back. Unfortunately, though, it was too late for them to be all that useful to Moholy—the books and publications and gallery shows had all mostly come out. When she passed away in 1989, Moholy’s collection of negatives were donated to the Bauhaus Archive in Berlin, where they continue to be preserved and studied.

Postwar architects were heavily influenced by Bauhaus designs. In a way, the ethos of the school was realized in this period: a more orderly, rational and civilized world was built through simple and functional design. Lucia Moholy was instrumental in capturing the school’s vision and helping it survive a war. And just like the other famous architects, designers and artists of the Bauhaus, we should know her name.

Comments (7)

Share

This episode was so good! I can’t wait to finish it this afternoon on the way home from work.

To end the episode with “Bella Lugosi’s Dead” by Bauhaus . Nicely done. Thanks again for a great, informative and entertaining episode.

What episode of Maximum Fun was the last bit of this episode from?

MBMBaM 316: Smart Stuff

Loved your fill in the mbmbam boys. Love your show so much thanks

Great episode, studying the Bauhaus at Columbia College Chicago (arts college) was one of my favorite topics during college. This information is a delightful addition to my knowledge of the Bauhaus school.

Every time I dwell on the Bauhaus school I feel like the school should be reopened. I like to think about how much more innovation the school would have contributed to global civilization if it was open during many decades since it was forced to close.

I am a huge fan of this episode! Thank you.