Few creative professions can point to a single figure as famous in their field as Frank Lloyd Wright. This architect’s legacy includes some of the most iconic and gorgeous buildings in the United States, such as the spiraling Guggenheim Museum in New York, the Fallingwater house in Pennsylvania, and the futuristic Marin County Civic Center in California.

By the end of his career, Wright had achieved a level of celebrity usually reserved for actors and rock stars. His was a household name, and he was recognizable by his distinctive hat, cape, and cane. He weighed in publicly on society, politics and religion, and he unabashedly claimed to be the greatest architect in the world. “You see,” he said in an interview, “early in life I had to choose between honest arrogance and hypocritical humility. I chose honest arrogance and see no occasion to change now.”

Frank Lloyd Wright went through a number of scandals in his lifetime. He was the subjects of lawsuits and property seizures, and constantly in debt or getting divorced. He was often criticized for his lack of professional conduct and general rudeness. He was largely characterized as arrogant and self-obsessed.

Fallingwater (left) and Guggenheim Museum (right) by Jean-Christophe Benoist (CC BY 3.0)

But this bombastic character ultimately changed the field of architecture, and not just through his big, famous buildings. Before designing many of his most well-known works, Wright created a small and inexpensive yet beautiful house. This modest home would go on to shape the way working- and middle-class Americans live to this day. And it all started with a journalist from Milwaukee.

A Trip to Taliesin

In 1934, a Milwaukee Journal reporter named Herbert Jacobs was sent over to Spring Green in Wisconsin. Though he knew little about architecture, Jacobs was assigned to write a story about Taliesin, Frank Lloyd Wright’s home and studio.

The night before Jacobs was to go meet the architect, his wife went into labor, and Jacobs stayed up with her until dawn in the hospital. The next morning, bleary-eyed, sleepless, and completely unprepared for his interview, Jacobs drove 120 miles through the cold gray Wisconsin countryside for his assignment.

Wright, who was 67 at the time, couldn’t have cared less about his appointment with the journalist and had forgotten about it entirely — not that unusual for a man used to blowing off reporters.

When Jacobs arrived, he got to spend only a few minutes with the master, before Wright said “some of the boys will see you now.” The boy were Wright’s so-called apprentices: architects-in-training who had come from around the world to learn from Wright. The two young men began to tell Jacobs about Wright’s philosophies and show him the campus of Taliesin (which is still there and running as an architecture school today).

“Taliesin” is a Welsh word meaning “shining brow.” Welsh, because the land was settled by Wright’s family from Wales (Wright spent many summers on this land as a boy), and “shining brow” because the main structure of the Taliesin campus wraps around the side of a hill, like a crown around the brow of a head. This structure reflects Wright’s philosophy that architecture should be integrated with nature. He thought architecture should help people live harmoniously with their environment, rather than shield them from it. A house, Wright believed, could work with the nature around it if it was made with local materials, had big windows, and was oriented for just the right amount of sunlight. All of these components are part of an overarching concept Frank Lloyd Wright called “organic architecture.” He wanted to spread this gospel to the next generation, which is why he returned to the valley he knew as a boy and established the Taliesin Fellowship.

This unconventional fellowship program was to be the subject of Herbert Jacobs’ article. At the time of his visit, the program had been running for two years and was a source of fascination for outsiders. Apprentices had to pay $1,100 a year to attend the Taliesin fellowship (nearly $20,000 in today’s dollars), which was not even an accredited institution. They also had to bale hay, plow fields, make meals and otherwise help around the school (all unpaid). But they got to learn architecture from Frank Lloyd Wright, living and working with him.

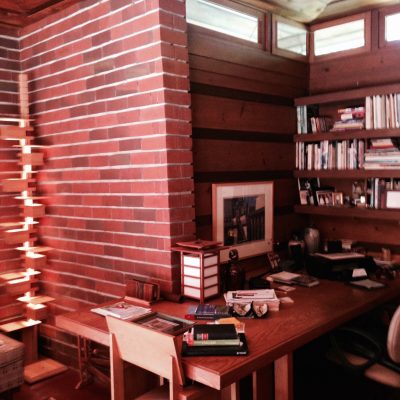

Wright was against wallpaper, paint and plaster– things that disguised materials. He felt that wood, stone and concrete should be celebrated and shown off as they are. Even the layers in composite materials like plywood could become elements of architectural ornamentation.

This was a significant departure from some more eclectic and decorative traditions popular at the time — things like gold ornaments, clawfoot bathtubs, lacy curtains and other highly-designed Victorian details. Organic architecture also eschewed the dull emptiness of glass and steel boxes of the Bauhaus and Modernists.

Wright ultimately broke from (and borrowed from) different traditions to create his own style, something specific to the United States and informed by its natural beauty. So while he composed forms using abstract geometries similar to those of Modernism, he also enlivened his designs using rich natural materials and textures.

Of course, as the apprentices were explaining all of this, the journalist, Herbert Jacobs, wasn’t paying much attention. He was preoccupied with thoughts of his wife and their child. On his way back home to Milwaukee, he called the hospital and learned that his daughter had been born in his absence. It was during those few minutes he had been talking with Frank Lloyd Wright.

At Home in Usonia 1

Herbert and Katherine Jacobs lived in Milwaukee for two more years before a slightly higher-paying journalism job drew them to Madison. When they arrived, they found most houses to be unaffordable on the salary of a newspaperman. At the suggestion of his wife’s cousin, The Jacobses set a meeting with Wright to see if perhaps the great architect would be interested in building them a modest home.

In the past, when Frank Lloyd Wright had designed private homes, it had generally been for a wealthier clientele (like the nearly 10,000-square-foot Robie House shown below).

Unsure of how to hook such an architect for their modest home, the Jacobs’ put it to him as a challenge: could he build them a nice house for $5,000 (around $85,000 in today’s dollars)? According to Jacobs, Wright responded that he had waited for decades for someone to ask him just that question.

Wright had long wanted to make a more democratic form of housing. He had experimented with inexpensive building methods and visionary urban (and suburban) design ideas. Now he had a chance to put some of these experiments and ideas into practice in a single project.

The Jacobs family would own the first house in a movement Wright called Usonia. This was a word he used to refer to an idealized vision of the United States at its democratic zenith. Usonia, Wright imagined, would be a nation of modest but comfortable, well-made and beautiful homes for the working- and middle-classes.

Usonia embodied an idea that proper architecture could shape culture — design could make the world a better place. A beautiful house, Wright thought, would inspire its residents to eat better, dress better, listen to better music, and be better people.

For Wright, housing the American people was a matter of individualization, mass-customization, rather than cookie-cutter mass-production . He saw America as a country of individuals, and his vision for the nation was one of decentralization, where people spread would out away from cities on private lots (a Utopian vision of suburbia), living independently, humbly, within nature.

“The city, of course, is a thing of the past,” claimed Wright. “There was a time during the middle ages when it was the only source of culture. There was no way of acquiring this thing we call culture except by direct contact, see.” But now that people had cars, radios and telephones, there was no need to congregate in dense urban clusters.

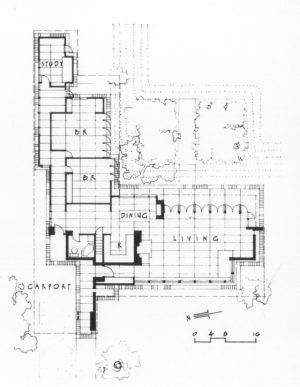

The first of its kind, the Jacobs House would become known as Jacobs 1, or Usonia 1. It is located in the suburbs of Madison and stands out very obviously from the surrounding homes. From the street and at a glance, it looks like a wooden wall — the house turns its back on the road. On the other side, expansive glass opens it the home up to nature. It was designed for its occupants, not to show off to neighbors.

Usonia 1 also features a carport, a now-familiar term reportedly coined by Wright. Instead of a garage, a wooden awning offers shelter for cars. This was a cost-saving measure as well as a lifestyle-shaping device, forcing occupants to discard rather than store extra stuff. And like so many of Wright’s architectural works, it is more than it first appears — a closer look reveals careful detailing in the arrangement of wood slats.

Usonia 1 carport and interiors by Avery Trufelman

Inside, the space is small but floor plan is open. There are no walls between the kitchen, living and dining rooms. Again, this was both a design strategy and cost-saving measure, of which there are many examples within the home. The lights on the ceiling, for instance, are just bare sockets with wires running through a steel channel — this is widely considered the first example of track lighting. Flat roofs, built-in furniture, and heated floors were also unusual if not unique features.

Not all of Wright’s strategies to save money on the construction of Usonia 1 were entirely above-board. He had his apprentices steal some bricks from another building of his that was under construction nearby, for instance, to save money on materials. These bricks from the Johnson Wax Building were curved, adding waves to flat walls. Wright also kept costs down by reducing his own fee to just $450, which was generous but also not a sustainable cost-saving solution going forward.

Still, though it had issues (like rain drainage) and was missing some things (like window screens), Wright managed to meet his target of building a low-cost home for the family.

The resulting house was small, but it worked for the family for a time. They moved out six years later having had two more children, but were clearly pleased with their residence since they once again commissioned Wright to build their next house.

A Vision of Usonia the Beautiful

In Wright’s perfect world, he would custom-design houses for everyone. And not just the architecture — he would design the dishes, furniture, maybe even the clothes (he once designed a dress for the wife of a client). This was all about changing culture, one home at a time, and by extension: redesigning America. Good design, he believe, would make the country more beautiful but also enlightened.

By the end of the 1930s, Wright had designed Usonian homes around the country, in states including: Alabama, California, Illinois, Michigan and Virginia. But this was just the beginning of his vision. He wanted to create a central factory that made prefabricated Usonian parts, modifiable for each client, depending on their needs for space and site conditions — a factory for mass-customization.

Frank Lloyd Wright’s factory for Usonian homes never came to be. And it became increasingly clear to Wright that the $5,000 dollar price tag for Usonian homes wasn’t feasible in the post-Depression era as materials and labor became increasingly expensive.

Meanwhile, Wright’s career picked up shortly after Usonia 1. He started getting bigger commissions again.

While Wright continued to work on Usonian homes within his lifetime, he would never find time to fully realize his vision. In the end, it was a group of his apprentices that would carry on his ideals by building an entire community of Usonian houses.

Comments (25)

Share

We live in a Usonian (Arnold house, Columbus WI, Storrer #374, Pfeiffer #5401). It’s a work of art that we appreciate every day.

Ah, finally! I was hoping you would do a story on FLW and glad you focused on the Usonian architecture. Great episode! Got to tour the Gordon house down in Oregon and its interesting how big it feels when you’re inside of the house even though its roughly 2000 sq ft.

I loved the “next time on 99pi”. It’s good to know that you are doing sequenced stories. It was a good feeling.

Here’s a nice video tour of the first Jacobs house on YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=r7HiZNeKmuA

Umm, Spring Green in not in Central Wisconsin. Your own wikipedia link proves that.

Wausau, Mosinee, Stevens Point, Marathon, Marshfield, that’s Central Wisconsin.

In the early 60s we moved into an Eichler house, 782 Holly Oak Drive, Palo Alto, California. Living in that house was indeed inspiring. Until this podcast I had no idea how much that design derived from Wright. Thank you for this podcast. I can personally attest to the positive effects the Usonian design had on our living experience. It was a cheap tract house. But it was by far the best house I’ve ever lived in. And now we have McMansions. How sad. Design matters.

Wright’s Usonian’s remain my most favorite of his works, including Robie, etc. I live in Madison and I’ve made my pilgrimage to Jacob’s 1. It is my near ideal home. The wall of windows/doors, the wall of built-in bookshelving, the built-in desk, the fireplace, the mix of brick and cedar, the ceiling (actually sculptural in design): all elements I would love to have in a home I own. It is “near ideal” because I’d prefer a larger kitchen.

Thank you for an excellent article!

I listened to the podcast first, so I had no idea what the house looked like. I expected from the descriptions that it would be far more sparse and utilitarian.

But, wow… the house is gorgeous!

Architecture-related shows are always welcome! I can see so much of Wright’s vision in some of the mid-century modern homes in 1950s Houston suburbia. Am thinking specifically of this neighborhood, which is slowly being eaten away by tall “McMansions.” A BIG loss for history, but (I must admit) a win for energy savings…

http://memorialbendarchitecture.com/bend.htm

Follow up… now the very same neighborhood is quickly being eaten away by demolition, with a few permits a week being granted by the city. Reason: The quiet creek behind the homes, which has generally stayed in its deeply scoured clay banks, overflowed during Hurricane Harvey, filled an 18-acre freeway trough 20 feet or more with floodwaters, deliberately released upstream in the hopes of saving the city from a greater fate. Come back in five or ten years and see how the court decisions go. It should make an interesting story.

I live in Madison and lived a few blocks away from the Jacobs House and walked by it all the time. I had to laugh when you said that it was in a “suburb” of Madison. I doubt that anyone who lives in that neighborhood considers it a suburb on the edges of Madison. It is a good 2 miles from the edge of Madison in any direction. Yes, it was on the edge of Madison at the time it was built (the house we lived in was built in 1947 on old farmland), but now is considered very much in Madison and not on the outskirts.

We watched when the house was restored and toured it after. What is not while many of the design elements are elegant (such as the window wall and the heated floors) others are rather impractical. The bedrooms are very tiny and have almost non-existent closets. I now live in a house that was built in 1938, so I know what small closets are, but the ones in the Jacobs house are small even in comparison. Also, as other have noted, the kitchen was not designed by anyone who ever cooked.

That said, it is a beautiful house from the outside and the restoration was very well done. But if you read on the website what all had to be done, it was extensive.

It’s a weird way to phrase it but it’s certainly in the typical suburban-type area. It’s not rural, and certainly not as dense as the urban residential areas you’d find on the Isthmus.

I thought the same thing! Very much in the city.

Lovely house, but I find it interesting that it is referred to as a very small space and wasn’t big enough for a family at 1550 sqft.

Coming from England, our house is a 3 bed terrace with a total floor area of 740 sqft, so about half the size of Usonia 1.

To me, Usonia 1 sounds huge!

Wow. I didn’t notice that detail. That is huge! (To me, living in a 950 sq ft 1920 bungalow with two kids and a spouse)

Episodes like that are why we love 99pi. Keep the great work! I can’t wait to listen to that second part

Grew up in a Usonian house designed on Wright’s principles by Edward Dart. Created a very unique aesthetic awareness and extreme sensitivity to the natural world. Ever grateful for being raised to be the kind of person FLlW wanted his design to create. It does!

There is a fully restored and beautiful FLW Usonian home that was relocated to Crystal Bridges art museum in NW Arkansas. It is free and open to the public for tour, which I think is great. When touring one of the biggest surprises to me was feeling the radiant heating found within the floor that also extended outside onto the patio. From what I understand there is a family of raccoons who very much enjoy sleeping on the warm patio during a cold winter night. The house was designed on a 4×4 grid system, clearly the intent was for the owner to contact FLW when they were ready to add on. The size is perfect for a small family and I love the carport cantilever. Check it out if you’re ever in the area. The Bachman-Wilson House. Cheers.

http://crystalbridges.org/frank-lloyd-wright/

Florida Southern College in Lakeland, FL has the largest concentration of FLW-designed structures, and in 2013, they built a beautiful Usonian house and renamed the street Frank Lloyd Wright Way. I live nearby, but didn’t know the history of the house until now.

I’ve been told that he hated tall people and often made ceilings low to make them uncomfortable. I’m 6′ 4″, and I imagine him laughing in his grave each time I visit the campus.

As usual you did an amazing episode… I discovered how amazing when based on your descriptions I realized we live close to a whole neighborhood built on Usonian principals and now protected as a historic district. (http://arapahoeacres.org/architect/usonian.html) That an audio story gave me such great visual information is impressive. I can’t wait to go walk around and get a good look at the houses… In the meantime I’m reading more. Thanks for stimulating my curiosity about something I knew nothing about previously!

Great episode! Now it has me thinking about whether anyone is trying to do this today? The tiny house movement seems to fully embrace many of these ideas – economy, frugality, creative use of space / spaces that serve multiple purposes, living with less. I have a hard time believing that anyone could build a 1,500 sq. foot house that could actually house a small family today for under 100k. Even under 200k here in Colorado or any growing metropolitan area seems nearly impossible. How about in Oakland?

Where can I find music form this episode? Do you publish original music?

Anyone ever mention the connection between one of Wrights earlier employee’s, Rudolph Schindler & the close spatial layout of Schindler’s own home in Hollywood from 1921, where Wright actually spent the night i believe. Did he know this space and borrow some of the spatial moves but fit it to a more nuclear family layout?

You can now stay in a Usonian Air B&B!

https://www.airbnb.ca/rooms/16024637

Awesome Wright created a small and inexpensive yet beautiful house.