The evil corporation has always held a special place in film. From Blade Runner’s Tyrell Corporation to Robocop’s Omni Consumer Products and beyond, dystopian capitalism is a staple of many films’ most successful antagonists.

What’s fascinating about the evil megacorporation is that its architectural aesthetic has remained virtually unchanged throughout its history: brooding Late Modernist (AKA High-tech or Structural Expressionist) buildings have become a well-worn trope, reaching a peak during the sci-fi smorgasbord of the 80s.

Modernism has always been at the forefront of the sinister in film, as seen in Fritz Lang’s Metropolis with its Art Deco styling and every Bond villain’s house ever. But the architecture of Evil, Inc. is almost exclusively from the Late Modern period, which spanned roughly between 1960 and 1980. Let’s look at a few examples:

Robocop (1987)

Though the story of Robocop takes place in futuristic Detroit, the film was shot exclusively in Dallas, Texas. Set in a dystopian future where the Omni Consumer Products corporation controls the city of Detroit, the 80s film features at the heart of the evil corporation a Late Modern building by I.M. Pei: the Dallas City Hall.

Dallas City Hall was built in 1978 and is an example of Brutalism, a modern architecture movement lasting from around 1950 to 1980 that focuses on the sculptural use of bare concrete. The term Brutalism comes from the French beton brut meaning raw concrete.

Why use Dallas City Hall for the headquarters of an evil corporation who rules everything with an iron fist?

The answer comes from the fact that Brutalism was an extremely popular architectural style for government buildings in the 60s and 70s — it was inexpensive to build while still appearing Modernist. During the 70s especially, some of the most notorious government buildings were constructed in this style, giving bureaucracy an unintentionally sinister air.

Perhaps the most famous such structure of the period is the J. Edgar Hoover FBI Building in Washington, DC:

Designed by Charles F. Murphy & Associates and constructed in 1975, this building became the poster child for sinister government architecture (and the fact that the FBI was housed inside didn’t help this perception much.) The building’s aesthetic became synonymous with surveillance and policing in general — for a movie about a rogue cyborg cop, choosing that aesthetic was basically a no-brainer.

Blade Runner (1982)

The 1982 film adaptation of Philip K. Dick’s novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? has a pretty star-studded cast of architectural cameos – including historical Los Angeles icons such as the Bradbury Building, Union Station and Frank Lloyd Wright’s Ennis House.

Two interesting aesthetics are at work in this film, present in one real building and one fictional one. The real building is the Bonaventure Hotel, featured in the opening act of the movie where Deckard, our android-hunting mercenary protagonist, has a run in with a cop.

A glass-and steel-monolith built in 1976 is instrumental in establishing the futuristic dystopian mood of the film. Designed by architect John C. Portman Jr., the hotel epitomizes the era of Late Modern corporate architecture. It features vast curtain walls in interesting shapes, with the divisions of the windows not necessarily reflecting the size of the spaces behind them and obfuscating the scale of the building in relationship to the human form.

A glass-and steel-monolith built in 1976 is instrumental in establishing the futuristic dystopian mood of the film. Designed by architect John C. Portman Jr., the hotel epitomizes the era of Late Modern corporate architecture. It features vast curtain walls in interesting shapes, with the divisions of the windows not necessarily reflecting the size of the spaces behind them and obfuscating the scale of the building in relationship to the human form.

The building is both futuristic and dated — it also looks like anything but a hotel. The reflective glass facade is unwelcoming — it exhibits the same unsettling monumentality as Dallas City Hall but executed with different materials, making it well-suited to the cyberpunk world of Blade Runner.

The other main set building in the film is the headquarters of the fictional Tyrell Corporation, which owes its design to other interesting design movements of late modernity.

The Tyrell Corporation, the sinister entity behind the movie’s rogue androids, is housed in a futuristic temple of evil that takes its influence from two places: Late Modern architecture by architects such as Kevin Roche and Philip Johnson, as well as the High-tech movement spearheaded by architect Richard Rodgers.

The building that immediately comes to mind upon looking at the Tyrell Corporation is the Pyramids, a complex of buildings in Indianapolis designed by Kevin Roche and constructed in 1972:

Built for the College Life Insurance Company, these structures epitomize the changing image of Modernism, from one of International Style restraint, to one of sculptural Expressionism; in Roche’s case, exploring the use of glass to play with elements of mass and scale to give something so fragile a new expression of monumentality.

The other influence of the Tyrell Corporation comes from the so-called High-Tech movement of architecture, which took the aesthetic of the machine to its logical extreme. The most famous work of this style was the Pompidou Centre in France, designed by Richard Rogers and Renzo Piano, built in 1971, which turned the world of architecture completely on its head.

The idea behind High-tech architecture was that the structure of a building could be expressed by its exterior. While Brutalism accomplished this by using sculptural forms to reflect the structure of the building’s interior, High-tech architecture literally put the building’s “innards” on the outside, giving the hidden mechanisms of a structure their own expression.

Intentionally or otherwise, the buildings take on an industrial sheen, certainly welcomed into the aesthetic language of films like Blade Runner. The combination of the corporate sheen of Roche and the pseudo-industrial language of Rodgers pair nicely when the subject matter is an evil corporation in an gritty future Los Angeles that manufactures fake human beings. The two aesthetic languages were never merged in real life, partially because one was quintessentially American and the other European, which makes their integration in Blade Runner especially fascinating.

Total Recall (1990)

Like Blade Runner, Total Recall is based off of a story by Philip K. Dick, and was filmed by the same director as Robocop. The director originally wanted to shoot the film in Houston, but it was moved to Mexico City due to budget constraints. The mind-bending plot, revolving around Arnold Schwarzenegger’s character believing he’s been implanted with false memories, is well suited to the aging Modernism south of the border. The film features the Hotel Nikko, a 750-room behemoth built in 1985.

One of the interesting things about this building is that it is an example of how aesthetics from the United States took about a decade to become the norm in Mexico. A building designed in 1985 in Mexico fits into the US’s 1975 aesthetic language.

The concrete buildings of the 70s, endlessly replicated worldwide because of their inexpensive price tag, contribute heavily to a sense of placelessness in an increasingly global world still entrenched in the armaggeddon rhetoric of the Cold War. The facelessness of the modernist architecture of Mexico City featured in the film contributes to the delirium and helplessness portrayed by the plot. Ultimately, none of the filming locations were designed by famous Mexican or American architects, and the forgettableness of the buildings themselves ties in well with the movie’s themes of memory.

The Matrix (1999)

The mind-bending film The Matrix, which immediately became a pop-culture sensation upon its release, also deals with themes of the nature of memory and what it means to be human. Filmed in Sydney, Australia, the film features elaborate chase scenes throughout the city’s rich urban fabric. One of the most iconic buildings of the film is the Metacortex firm where Neo works as a programmer (and begins to suspect that something is not quite right in the world). The Metacortex building is actually Sydney’s Met Center, a shopping center built in 1980.

What’s interesting architecturally about this building is that it bridges the gap between glass-pane Modernist corporate architecture and the Brutalist architecture of late modernity. The building features the Brutalist monumentality in its concrete spine-like core, as well as the explicit articulation of interior space on the exterior. The glass volumes, separated by the nodes of the spine, are cantilevered along the building’s sides and sculptural in and of themselves. In a movie about people being brains in vats, the building’s spine metaphor fits in with a dark technocratic world.

But why did producers choose the architecture of Late Modernism, as the face of sinister megalopoly?

Modern architecture from its inception has always been associated with the coming of the machine. The movement’s founders in Europe believed that the architecture of the time laid in the hands of industry – factories, concrete silos, and other functional, rational buildings. New technology like steel and reinforced concrete enabled architects to come up with dramatic and powerful forms — these were previously unattainable with iron, wood, and masonry. Because of this new technology, ornament was seen as frivolous — it could be removed or separated from the structure itself and merely applied to the outside.

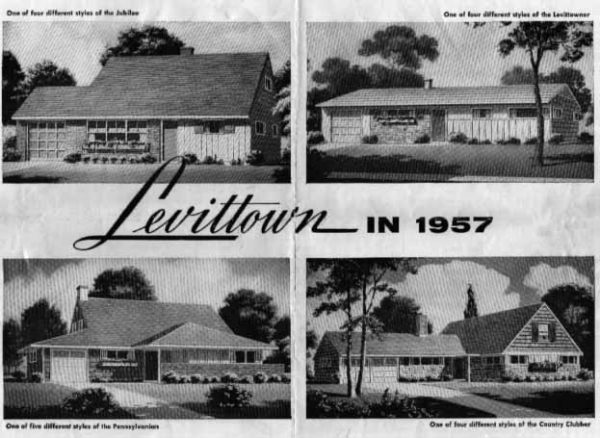

While this was all very interesting for the world of architecture professionals, millions of people toiled away in factories every day. The idea of coming home to a building that looked like the factory was abhorrent to many of them. Thus, modernism was restricted to public buildings, corporations, and isolated houses while the rest of the public post-war built Levittown.

If the cute little house with the white picket fence was the home of wholesome goodness, then the modernist skyscraper was its antithesis. As the 20th Century moved forward, the machine aesthetic of the 20s popularized by the Bauhaus was wearing thin. Eventually, the philosophy of architecture became fractured in the 1960s and 1970s, the period during which many of the buildings most loathed by the public were constructed.

In addition to architectural fragmentation, the 60s and 70s were a heavily fractured time politically. This was the era of Vietnam, a population explosion, environmental crisis, the energy crisis, and other dismal and depressing events. In the boom of the 80s, a wealth of great science fiction films came out with dystopian elements at the core of their stories, their aesthetics drawing on past precedents.

The fascination with corporate control and its absence of ethics coupled with new technology (spurred by the beginning of the home computer) culminated in some of the era’s best known speculative fiction film, all of which used the architecture of Late Modernism as a backdrop for evil.

Comments (6)

Share

Would the Jubilee Line extension in London (built mid-late 1990) fit in here? It’s all bare concrete, flat glass and cavernous spaces. It still looks badass, so much so that some of it is being used as the Death Star* in the new Star Wars movie.

*at least that’s what I presume.

Love the article, although I think describing the Tyrell building as a “temple of evil” is stretching the truth to make a point. The place is presented as distant, edificial, Olympian, but always romantic. It doesn’t really FEEL evil, and I don’t think we’re meant to experience it that way.

I think it is wrong to call Bauhaus a machine aesthetic. Bad imitations that copied obvious design elements but not the spirit created that impression. Original Bauhaus creations feel very human and even playful – just without certain traditional ornaments. I’m a bit of a fan and I’ve visited the original Bauhaus in Dessau.

Checking out https://www.reddit.com/r/evilbuildings/ for even more examples is strongly recommended.

What about the Energy Corporation building in the 1975 film Rollerball? That should have been mentioned.

Yeah it’s one person’s opinion – in 2017 no less – to call the Tyrell Buildings ‘ Evil ‘ …

There is something to the overall theme and schema , but this is well, simplistic to say the least.

My friends consulted on the Bladerunner designs and they were not looking at the building you posit as example.

Anyway … “have a better one”