In 1996, President Bill Clinton and the Congress undertook a reform effort to redesign the welfare system from one that many believed trapped people in a cycle of dependence, to one, that in the President’s words, would give people “a paycheck, not a welfare check …. Today, we are ending welfare as we know it.”

Many of the key components implemented by Clinton can be traced back to a bureaucrat named Larry Townsend and a pilot program he operated in California called GAIN (Greater Avenues for Independence). Head of the welfare office in Riverside County, Townsend didn’t have much patience for the education-and-training route of existing welfare programs—the ones which helped welfare recipients gain more skills so they would fare better in the job market. Townsend’s approach was much more straightforward: get people into jobs as fast as possible.

Before Townsend and Clinton, the prevailing philosophy around welfare was that single mothers needed it so they could afford to stay out of the workforce and raise their children. As middle class moms began entering the workforce in greater numbers in the 1970s and ’80s, politicians began to question this idea of long-term welfare. Some programs of the era focused on helping moms get GEDs or vocational training, providing educational paths toward higher-paying work.

Townsend’s answer was to redesign the welfare program in Riverside, California around the more immediate search for jobs—not the perfect job, but any job. People on welfare were now part of club, not unlike weight loss groups, where the search for jobs was supported by slogans and cheers when success was achieved.

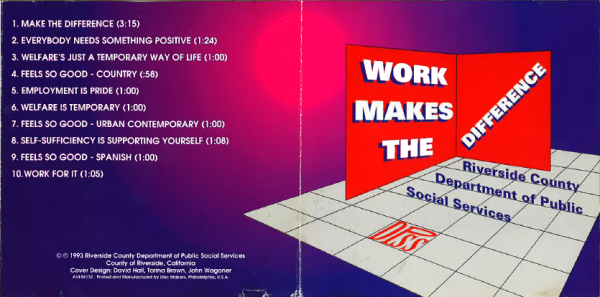

Townsend not only preached about the beauty and glory of work, he even commissioned a musical album with inspirational songs about getting off welfare. The tunes would play in the waiting rooms of welfare offices and as hold music for phone calls. These genre-spanning songs ranged from country to rap and R&B. They were written, composed, produced and recorded by the staff of the Department of Public Social Services headed by Townsend. You can listen to the full album here!

The Riverside program became highly visible and the subject of research studies. Sociologist James Riccio and his team followed the families who had participated in the program. On average, the earnings of families in the Riverside program had climbed a surprising 42 percent over those in the control groups, including those that had emphasized education first in their approach.

These positive results made Townsend a star in the world of welfare reform. In 1993, Tom Gorman of the Los Angeles Times wrote, “Riverside is pursuing a notion so obvious as to be stupefying …. If you want people to get off of welfare, stay on their backs until they get a job.” On five different occasions, Townsend testified before Congress. He came to be known as “The Magic Bureaucrat” and his program became known as the “Riverside Miracle;” many program elements found their way into the welfare reform bill passed in 1996 (formally known as the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Act).

But within a few years it became clear that the “Riverside Miracle” wasn’t so miraculous after all. In the early 2000s, Joe Hotz, a Duke University economist, returned to Riverside to check on how welfare recipients who had gone through the program were doing. They compared these subjects to those participating in other California programs that had focused on education and training. What they found was that the effects of the “Riverside Miracle” had all but disappeared.

Yes, the program had shown positive results in the early years, but within a decade the effects reversed. People who had gotten more education and skills training were now more likely to be working and less likely to have returned to welfare.

This reversal had to do in part with the conditions in the larger economy. By 2000, the job market for low-skilled worker had changed and low skilled jobs were hard to find. All the encouragement in the world couldn’t help people on welfare find jobs that didn’t exist.

This discovery came too late. The Riverside program had inspired a raft of federal legislation built around the “get a job, any job” approach, the apex of which was Clinton’s 1996 bill. Neither the federal government nor the states that ran the welfare-to-work programs had the political will to rethink the programs, which they had worked already to reform.

And many of the people who went through the Riverside Miracle are still dealing with the bittersweet aftermath.

Some, like Sophia Elsman, have been off welfare ever since going through the program. Sophia works as a dress shop manager, but still makes less than fifteen dollars an hour. She looks back to the Riverside program and wishes she’d be encouraged to get some training—to do what she really wanted to do. “I wanted to be a nurse.” As a nurse, she’d be making a lot more money than fifteen dollars an hour.

This story was originally produced for The Uncertain Hour, “an immersive docu-pod that reveals the origin stories of our economy in unexpected and provocative ways. Host Krissy Clark dives deep into one topic each season, unpacking what we see as normal to show it didn’t just happen. Brought to you by Marketplace‘s Wealth & Poverty Desk, the first season explores the uncertainties of welfare.”

Finally, a shout out to P.O.S, of the always excellent Doomtree collective, who mentions Roman Mars in his new release. Listen above (especially around the two-minute mark!) and buy the track on iTunes.

Comments (14)

Share

So where can anyone listen to the songs off the album?

I’ve been trying to find any trace of it online, and have come up empty. Please let me know if you have any luck…

Here you go! http://www.marketplace.org/2016/08/17/wealth-poverty/uncertain-hour/s01-7-album-work-makes-difference

Uhhhgggg…. This Podcast has officially become too Regressive for me. Sound the Death Knell of Classic Liberalism.

And also Roman, just so you know, the coin check might seem like a cool nuanced thing for you, but those if us who actually served the coins we have actually mean something…. so that was obnoxious too.

Peace out!

This story was annoying. Particularly, the women’s story at the end. She clearly benefitted and the tax payers funding her welfare benefitted by her getting a job. Her decision to not seek additional education over the next 20 years is hers alone. To suggest she could have received training to be a nurse (a RN specifically) is laughable – why not give her training to be an astronaut while we are at. Becoming a nurse requires significant training and intelligence. I’m not suggesting the women was inept, but nursing isn’t really a career the government could train general welfare recipients to do. What’s wrong with expecting people to take some personal responsibility for their situation?

The education programs that they had before “Welfare to Work” would have precisely provided her with the educational opportunities that would have been a pathway to something like a career in health. Of course they wouldn’t just magically make you a nurse or whatever, but they would give a clear ladder for someone to go through the program, to community college, to gainful employment as, if not a nurse, something more aligned with her career aspirations. The difference here is where you draw the line between “personal responsibility” and “lack of opportunity”, which is what welfare is meant to bridge. Whether you like it or not, the Education and Training model has proven, (not just in the states but internationally) to be more beneficial in the long term to the career prospects of participants, as well as the economy overall (more high-skill workers).

I think a lot of this comes from an inherent “sense of fairness” that people have different sensitivities to, and it’s something that is frankly hard to step outside of. Humans have an inbuilt, evolutionary bias to despise “free-loaders” or people they think are “gaming the system”, as well as a host of other deep-seeded heuristics. Unfortunately, sometimes these instincts are ill-suited to practical realities in the contemporary world, which is far more complex than the tribal situation we’re all hard-wired for.

I really, really need a copy of this album. I’ve done some googling and come up empty. If anyone has any info on where/how I can get a copy, digital or otherwise, I’d greatly, greatly appreciate it…

You can find the album and his other music on spotify.

/Belgian

Hey Roman – the gentleman interviewed in the podcast referred to a list of sayings about work he had collected. Is that list available anywhere?

Wow, I was not expecting to hear a POS track at the end of that podcast. Or any podcast really. I can see how POS would listen to 99PI, and how roman would listen to POS, but it’s still a surprising connection.

For anyone curious about POS, the track on the podcast is representative of his more recent work, which taps into his punk-rock roots and has a rougher feel to it. His earlier work generally is generally more polished and “clean” sounding (I mostly refer to the production and beats, his delivery and lyrics are always an interesting combination of aggressive and intelligent).

For an example of his earlier style, I’d recommend his 2009 album “Never Better”, which you can listen to for free on the label’s website here: http://www.rhymesayers.com/neverbetter/

Is one of the tracks from this episode from Sakamoto Shintaro’s “Sticks and Slacks”?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U3M7o19Z7FA

Thank you 99% Invisible and The Uncertain Hour for this episode. This is a good introduction to the failures of welfare reform or “workfare.” In fact, there has been even more follow-up research done on the effects since the 1990s that show the negative impact these policies had. I can imagine it was uncomfortable for your reporter to ask about the “stereotyping” of welfare recipients — she shouldn’t be because research and scholarship has established that race and gender have impacted not only the development of welfare programs in the US but also contributed to a feedback loop to stigmatize its recipients as “undeserving.” Also, I also want to point out that the work-first approach, into low-wage jobs, is also how our refugee resettlement program works. We measure success based on entrance into low-wage jobs and getting off of welfare. We don’t help professionals get re-credentialed, and in the long-run that hurts the refugees, their families, and reduces the amount of taxes they pay because of their lower incomes. It wasn’t always like this. We did offer education to training to Cuban refugees in the 1960s. It’s a shame that stereotypes, biases of “fairness,” and a lack of political will get in the way of giving people a meaningful way to get themselves out of the cycle of poverty. This is what education should do for people.

I was very disappointed with this episode. It exaggerates both parts of the story for the sake of entertainment. Things are not black or white. A big part of Mr. Townsend’s approach makes a lot of sense to me and his motivation and passion are something you seldom find in public workers.

My experience is that entering the job market as soon as possible is as important as ongoing education. That’s the base of apprenticeship programs. Maybe Mr. Townsend missed part of the equation (continuous education) but he still deserves significant credit for his work.

In my opinion good journalism is dissecting and explaining complex problems, not reducing them to a good/bad choice.

I’ll bet you that 99% of the inspirational quotes he collected were not from people who were forced into the labour market without the benefit of a decent education.