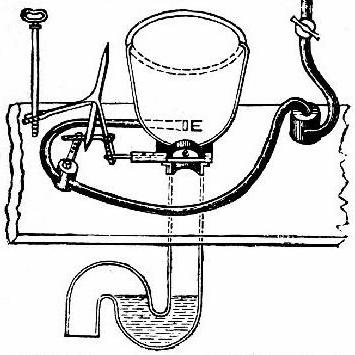

Every time you go to the bathroom, you should thank Alexander Cumming, the first person to patent a flushable toilet. Cumming’s great innovation was to hook up the toilet to an s-shaped pipe, which uses water to stop sewer gas from coming up and entering a home. Since Cumming’s brilliant invention, the flush toilet has become part of the ‘gold standard’ for sanitation, and a standard feature in hundreds of millions of homes. But as author Chelsea Wald argues, the modern toilet system is in desperate need of a redesign. This week, we talk with Wald about her book Pipe Dreams: The Urgent Global Quest to Transform the Toilet.

Most people don’t spend a lot of time thinking about their toilets, but the flush model is both a marvel and a failure of systems design. On the one hand, it has created a vast sanitation system that has helped add decades to human lifespan by reducing disease. But it’s expensive, and inaccessible for billions of people around the world, including several million Americans. Flush toilets also use about 100 trillion gallons of water every year, at a time when water is becoming more scarce. And the infrastructure needed to support a flush toilet, including a sewer system and wastewater treatment, has serious limitations. While there has been radical technological change in almost every other aspect of our lives, we remain stuck in a sanitation status quo — in part because the subject of toilets is taboo.

A potential revolution in toilets could have many benefits, including reducing inequality, mitigating climate change and water scarcity, and optimizing health. Author Chelsea Wald tells us about vacuum toilets from the Netherlands, smart sewer systems in the hometown of Mayor Pete Buttigieg, and the living nightmare known as “the fatberg.”

Comments (9)

Share

Many cities in the Bay Area split their sewage system from the storm drain system, that is why you often see stenciled goes to bay on the storm drain runoff in the street.

Fremont/Newark/Union City (Union Sanitation District) has a co-generation (power) facility at their treatment plant.

This podcast struck close to home.

I built a high efficiency house 10 years ago. We used a sawdust bucket toilet during construction to avoid a chemical toilet on site. Most of the workers thought that was pretty weird; but when you gotta go…

Then we installed a Puxin biogas digester

http://en.puxintech.com/hbs

which is comnected to our flush toilet and runs the main cookstove. For government approval we just sent in the forms with no extra comments and some civil servant just files it away un-noticed. Everyone who sees it says it’s a good idea. I have the forms for building them and in these 10 years of flawless operation and ‘show and tell’ only one other person (a plumber who helped install mine) has duplicated my system.

I have seen statistics that there are 200 million of these systems; mostly in the tropics. Mine appears to be one of the coldest installations on earth up here by 54.40 at the BC-Alaska border, buried under my greenhouse.

I truly believe toilets can help save the world, but we as a society can’t get past the yuck factor.

Chelsea Wald is probably a good journalist, and 99PI is very entertaining, but municipal engineers will be spluttering apoplectically at this podcast.

If you had a medical series, you’d probably get a doctor to check it for accuracy, but I suspect you didn’t find an engineer to comment on this podcast before broadcast.

To add balance, may I say:

Yes, much of the world is water stressed, but water used to wash sewage down the pipes is not ‘lost’. All of it eventually goes back to natural water systems. All of it, every drop. Most of it ends up in a river and is used happily as intake water by the next town downstream. A few towns in dry areas, like Windhoek, operate a closed system and pump treated effluent back into to join the intake of the domestic water supply.

South Bend, Indiana, may indeed have rainwater surcharges in their sewer systems. They probably have the cheap and nasty single trunk system that carries both storm-water and sewerage. As such, it is their decision to go with cheapness that leads to pollution; blame that. Don’t blame generic water borne sewerage. My town uses the widely adopted segregated system whereby storm-water travels in different (bigger) pipes and is discharged, untreated, into rivers and the sea.

The Netherlands experiment with vacuum systems is charming, but very expensive, so nobody replicates it. Pipes don’t deal with vacuum very well, as they tend to collapse, so you need costly strong pipes. Vacuum is not free like gravity, so you have to run a vacuum pump all the time. Their small packaged disposal plant is far more expensive per gallon than a big central plant. Burning residual solids (sludge is the trade term) is no innovation – it has been done for decades. Sludge is a difficult fuel.

It’s not true that sewage treatment works only use aerobic digestion. Most use both aerobic and anaerobic digestion. The anaerobic digestion produces biogas, mostly methane, which is burned on-site for process heating.

Also, energy intensive forced aeration with beaters or air pumps is a design choice. A less energy intensive and very common process for aerobic digestion is to trickle sewerage gently over high porosity filter beds (before fancy ceramics they used pebble beds).

Supplying non-potable water broadly is duplicating a system, and very expensive, but supplying lots of non-potable water to a few intensive users like breweries or paper works does work well. For domestic systems it is far better to use local captured rainwater (where available) for flushing and gardening.

OK, balance is not quite restored, but these inputs will go a long way in that direction

This was a great episode and I really appreciate the attention to the problem of wastewater management. I work for a Wastewater Treatment Plant and I wanted to share a couple of links that highlight efforts our city is putting forth to handle the problem of sewage overflows and the quality of water released into our river.

CSO Tanks always help by containing combined sewer material during high flow events and releasing it slowly back into the system in a way that does not overflow the pipes that deliver the sewage as well as the treatment plant itself at the end of those pipes.

https://spokaneriver.net/news/water-quality/city-of-spokane-final-and-largest-cso-tank-goes-on-line/

Our new next level treatment facility is a tertiary treatment that removes much of the plastic and phosphorus material that escapes into the river in a normal wastewater treatment plant.

https://my.spokanecity.org/projects/next-level-of-treatment-at-the-riverside-park-water-reclamation-facility/

The show neglected to mention the millions of us who already have a self-sustaining, natural way to deal with our waste at its source – they are called individual septic systems! In rural NH, I have been in our old house for more than 35 years, using a septic system that is even older. Our modern flush toilets deliver waste to an on-site holding tank, where natural microbes process the hard waste, leaving water to drain out a pipe into a leach field, where it naturally dissipates into the ground, which further purifies it as it seeps into the aquifer. A side benefit is being extremely aware of what happens to our waste and where it goes, and understanding what we need to do to keep it healthy, like not flushing anything but waste products, and not dumpling anything down our kitchen drains but water. If we aren’t careful, we could develop our own personal “fat berg” that we would need to deal with!

Where do I sign so that Roman never gets his audio logo?

My first experience with split water systems was on a visit to the Marshall Islands in 2003. The placement of settled areas on narrow atolls almost entirely less than 10′ above sea level makes fresh water scarce and complicates maintenance of infrastructure water supplies. Toilets and other things not sensitive to salinity use salt water. There is a non-potable piped water system that is used for things like showering, dishes, etc. Drinking water is purchased in 5 gallon containers. The big news when I was there was that the price for one of these containers had dropped from $6 to $5.

Something within the house still has to bring the waste from the bowl to the sewer and currently that’s water. All of those toilet designs address the toilet, but not really what happens below the closet flange to move that waste out of the house.

Almost anyone who grew up in a riverfront town (I did, Cincinnati) learns that one town’s effluent is the next town’s intake water. That’s just how it is. So I am always surprised when folks in California get apoplectic about “recycled toilet water” – especially when the recycling process includes a pass through the soil into an underground aquifer. Where do these people think their drinking water comes from? I know, I know … they don’t.