When 99% Invisible producer Katie Mingle’s father Jim Mingle retired, he began walking — a lot. He’d always been a walker, but with more time, he took up long-distance, multi-day trips. And even though he’s an American, he mostly preferred to walk in the UK. In fact, over the course of a decade, he walked the entire length of Great Britain.

On one of his many trips, Jim found he needed to hitchhike (rather than walk) back to the village where he was staying. A jeep pulled up and he hopped in. The driver was dressed in a traditional tweed outfit with a funny cap. He introduced himself as the gamekeeper for Madonna and her then husband, Guy Ritchie. Katie’s dad had been walking across their private estate.

This walk across private land was not unusual. Thousands of distance walkers in Britain, regularly do the same thing, which is different from what people typically do in the United States. If you wanted to walk across America, you’d have to do it on a combination of public trails and roads and you certainly couldn’t cut across Madonna’s property.

In the United Kingdom, the freedom to walk through private land is known as “the right to roam.” The movement to win this right was started in the 1930s by a rebellious group of young people who called themselves “ramblers” and spent their days working in the factories of Manchester, England.

Manchester was a dirty, grimy industrial town in the 1930s, but close to a beautiful area known as the Peak District. However, this open countryside was closed to the workers of Manchester at the time.

It hadn’t always been this way. For hundreds of years, an idea of “the commons” had existed in England. From about the 5th to the 15th century, kings and lords controlled all the land but peasants had rights to live on it and use it in exchange for various type of service.

Ken Ilgunas, author of This Land is Our Land, says that peasants in England could graze their cattle, cut lumber, draw water and collect peat from these common lands.

Beginning in the 1400s, when wool prices rose across Europe, landowners began fencing their land in order to graze sheep more efficiently —an act that became known as “enclosure.” Landowners cleared entire villages of people, making them homeless, and put up stone walls and hedges to mark the boundaries of their property.

Over the years, Parliament created more and more laws to keep landless farmers and agricultural workers from using what was once common land. From 1760 to 1870, about a sixth of England went from common lands to enclosed private property.

People were so desperate to continue hunting on this once-common land that they came at night and covered their faces in soot for extra camouflage. They were known as “the blacks,” and in 1723 Parliament passed the Black Act, which created a number of offenses related to trespass, some of which were punishable by death.

Eventually the death penalty for trespassing was eliminated, but the land remained closed to the vast majority of people. As England industrialized in the 1800s, workers were further separated from the land and unable to find places for recreation.

England did not have a national park system at this time, and the trails that people could access were extremely limited. They walked where they could and trespassed where they couldn’t. They climbed over fences and tried to stay hidden from the gamekeepers. And all over England, so-called rambling clubs started to form. And in polluted, industrial 1930s Manchester, there was a rambling club called the British Worker’s Sports Federation and a charismatic member named Benny Rothman.

One day, a few people from Benny’s group were walking in the hills near Manchester, but they were soon chased off by gamekeepers employed by the landowner. Benny and the other ramblers thought: if there were enough of us they couldn’t stop us. Let’s get a huge group together and walk onto this mountain called Kinder Scout.

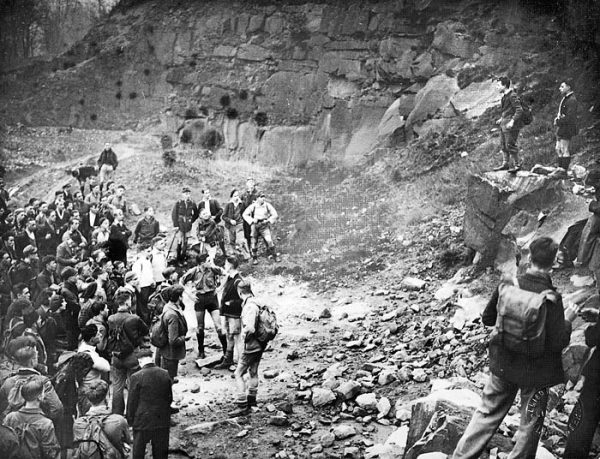

A motley crew of hikers gathered at the base of the mountain, and Benny Rothman talked about the rights they had lost during the enclosure acts. He emphasized that the trespass on Kinder Scout was meant to be peaceful. And with that, the group set off up the mountain. At some point, the hikers did have a small scuffle with some gamekeepers, but the keepers backed off after they realized they were outnumbered.

The trespass was a success. They openly walked on Kinder Scout and it all probably would have ended right there if the police hadn’t decided to make some arrests. Six ringleaders were arrested and five were later given prison sentences from two to six months. The effect of this was to give the trespass national attention and a lot of popular support.

The young ramblers of Manchester had set in motion changes that would transform how England thinks about private property. The Kinder Scout trespass has been described as one of the most successful acts of civil disobedience ever in the history of the country.

A folk singer named Ewan MacColl memorialized the event with a song:

… I’m a rambler from Manchester way

I get all me pleasure the hard moorland way

I may be a wage slave on Monday

but I am a free man on Sunday.

After the trespass, the rambling groups continued to push for expanded access. There were more trespasses, and in 1951, when Britain opened its first national park, it was in the Peak District.

But it wasn’t until the year 2000 that the ramblers got what they always wanted — an act of Parliament that opened up huge sections of the country where people could roam free.

Other European countries have similar laws, and some have gone even further. Norway, Finland, Sweden and Scotland provide nearly universal access to the whole countryside.

In the United States, we have an incredible system of national parks, but very few rights to wander through private property. The idea of opening up private land to the public seems almost un-American.

But that wasn’t always the case. In the early days of this country, it was common practice to hunt and fish on private land if it wasn’t enclosed by a fence. In an 1862 essay entitled, “Walking,” Henry David Thoreau wrote that he feared that one day, “walking over the surface of God’s earth shall be construed to mean trespassing on some gentleman’s grounds.” That day may have come even sooner than Thoreau feared. Ken Ilgunas says our concept of private property began to change just a few years later, following the Civil War. Louisiana, shortly after the end of the war, criminalized trespassing in part as a response to former slaves now having free access to the countryside.

But that wasn’t always the case. In the early days of this country, it was common practice to hunt and fish on private land if it wasn’t enclosed by a fence. In an 1862 essay entitled, “Walking,” Henry David Thoreau wrote that he feared that one day, “walking over the surface of God’s earth shall be construed to mean trespassing on some gentleman’s grounds.” That day may have come even sooner than Thoreau feared. Ken Ilgunas says our concept of private property began to change just a few years later, following the Civil War. Louisiana, shortly after the end of the war, criminalized trespassing in part as a response to former slaves now having free access to the countryside.

There were other reasons as well. With the invention of barbed wire, the open ranges all but disappeared. Native Americans were forced off their communal lands onto reservations. The land was then sold to settlers and fenced. Land-grants to the railroads and the Homestead Act of 1862 turned great swaths of public land to private ownership.

Ken Ilgunas believes Americans should be fighting for the kind of recreational access that exists in many European countries. And so does Jim Mingle, who loved the freedom to walk across private land. “It felt like the whole country was open to you,” he says.

Comments (8)

Share

I can definitely see the line between “According to Need” and Serial Productions. Moving from one great home of podcast stories to another. All the best Katie.

Just a point of order, British gamekeepers of that time tended to drive land Rovers, probably a Defender. Not a Jeep. Although the first Land Rover was pretty much a rip-off of a wartime Willies Jeep.

However we call vacuum cleaners hoovers and Pretty much any cola Coke! I think there must be a 99% invisible podcast on generic terms for such items.

One thing that was not clear in the podcast was the fact that Britain is covered with a network of ancient right-of-way with different classifications of use. Footpath’s may only be used on foot. Bridleways may be ridden, and some byways may be driven by carriage or even vehicles like jeeps, and land rovers 😉. Just to note there is no right to roam on agricultural land

Love everything you do!

Only the best wishes Katie!!! Thank you SO much for everything thus far and I look forward to your future things to come… may the road rise to meet you and the wind be at your back!!!

This episode was always one of my favorites. Thank you Katie.

Congrats Katie!

Congratulations Katie!

Thank you for the awesome work you’ve done in 99% , It’s so important to have queer people representing us, and the way you’ve told so many stories over here, it’s something else!

Excited for your next projects, and as always, congratulations to the whole 99% invisible crew, everyone involved with it, you guys are amazing.

Greetings from a brazilian queer girl!

There is no right to roam in England – only in Scotland – this episode is completely incorrect!

Insurance liability probably has more influence on not allowing people to roam freely on one’s land in the U.S. than anything.

You open yourself up to huge lawsuits if someone gets injured on your property.