There’s a scene in the buddy cop movie Rush Hour 2, starring Jackie Chan and Chris Tucker, that takes place in a crowded Las Vegas casino. After some tense action, a small bomb goes off near one of the roulette tables and money flies everywhere.

A company named ISS Props had provided the money for that scene (and several others) to the filmmakers. The fake money amounted to nearly a billion dollars in fake bills — and the company was surprised when one day, during the filming, two men from the Secret Service showed up to their office. The Secret Service was there because some of the fake cash had gone missing from the set and had started turning up on the Las Vegas strip. CEO of ISS Props, Gregg Bilson Jr., was now facing a serious charge: counterfeiting.

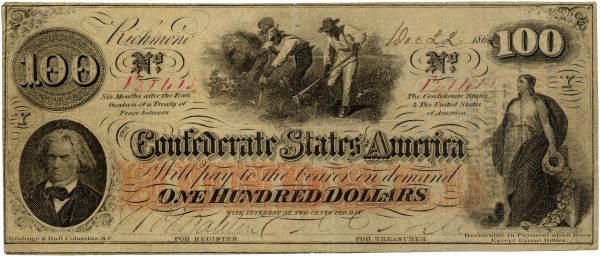

The U.S. has strict penalties for counterfeiting that can be traced back to the 1860s. Around the time of the Civil War, there was a lot of counterfeit money circulating through the country. The federal government needed to assure faith in its currency, so it got serious about cracking down on counterfeit bills. All reproductions of U.S currency became illegal, including photographs of money.

In 1865, a new enforcement agency was formed to help deal with the counterfeiting problem: the Secret Service. That agency is now part of the Department of Homeland Security and is generally associated with protecting leaders and their families. But in the beginning, they were part of the Treasury Department, and their only job was to fight counterfeiting.

In 1865, a new enforcement agency was formed to help deal with the counterfeiting problem: the Secret Service. That agency is now part of the Department of Homeland Security and is generally associated with protecting leaders and their families. But in the beginning, they were part of the Treasury Department, and their only job was to fight counterfeiting.

The ban on any photographic representation of money was in place for about a century, and this created a problem for people who worked in visual media, which came to include film.

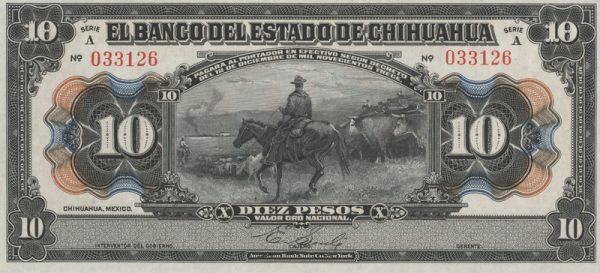

In the early days of cinema, when money was needed in a film, producers often used Mexican pesos. After the Mexican revolution ended (around 1920), a bunch of regional Mexican money that had been created during the revolution lost value and was sold for cheap.

The notes from the Mexican state of Chihuahua, where Pancho Villa held power, were some of the most widely used in film. Filmmakers weren’t really trying to pass them off as American dollars — it was just all they had to work with, and they assumed audiences either wouldn’t notice or wouldn’t care.

In the second half of the 20th century, the government began relaxing restrictions on the rules around photographing currency and it’s now legal to show real money in film. Using real money is great for scenes where you only need to show a small amount in a close-up shot. But for scenes where you need a lot of visible cash, it can be too risky. For those kinds of scenes, fake money is often preferred.

It’s now also legal to make reproductions of U.S. currency for use in film, but there isn’t a lot of clarity about how “real” fake money is allowed to look. Trent Everett, who oversees counterfeit operations at the Secret Service, says “it depends. It’s very subjective. If it’s the same size as a current U.S. currency note and it’s made in the likeness of our U.S. currency, then we view it as counterfeit.”

Over the years, prop money in movies has begun to look more and more like actual money. Some companies did (and still do) turn out bills that run afoul of the law, because prop money that passes muster for the Secret Service can look too fake when you see it on screen.

Some people make bills that are the same size as real money, but with one or two small design changes — it might say “In Dog We Trust” instead of “In God We Trust,” or have Benjamin Franklin making a weird face, or be stamped with a small disclaimer. All of these would probably be unacceptable to the Secret Service.

Some people make bills that are the same size as real money, but with one or two small design changes — it might say “In Dog We Trust” instead of “In God We Trust,” or have Benjamin Franklin making a weird face, or be stamped with a small disclaimer. All of these would probably be unacceptable to the Secret Service.

Gregg Bilson’s bills for Rush Hour 2 featured many small differences setting them apart from the real things, but they were still too close to reality for the Secret Service. Bilson had to turn over all of this prop money to be destroyed. They also confiscated and destroyed all the electronic files used in creating the fake money.

Bilson lost a lot of money — not just fake money, but the real money it took to produce the fake money. Bilson’s losses were in excess of $100,000, but he did not face any other penalties or jail time.

Bilson lost a lot of money — not just fake money, but the real money it took to produce the fake money. Bilson’s losses were in excess of $100,000, but he did not face any other penalties or jail time.

Fake movie money isn’t just leaking out of movie sets — It’s being sold on the internet on sites like Amazon.com, where anybody can purchase it. These fakes can look surprisingly realistic, even relatively close up.

Given how difficult it is to make money that looks real, but not too real, it’s hard to imagine who still wants to be in the business of creating and supplying fake money for the movies.

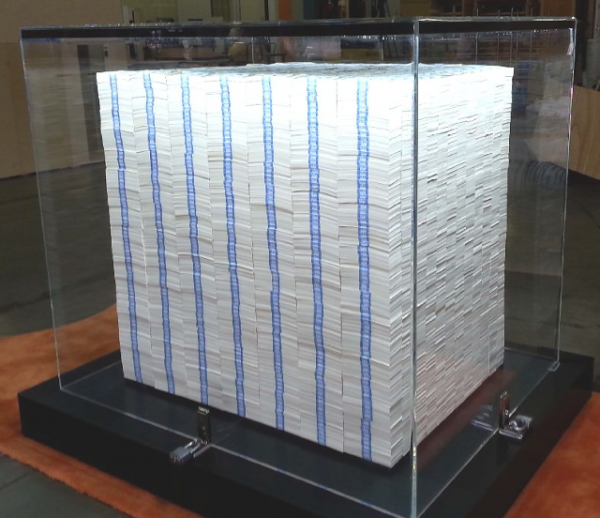

But there are a few people still doing it, including RJ Rappaport, president of RJR Props, which serves the entertainment and commercial advertising sectors. RJ’s warehouse is full of fake devices used by television and film productions, including futuristic-looking machines with lots of knobs and buttons and an entire room dedicated to prop money — palettes and briefcases of money plus rolls of cash.

Rappaport says it took three years of back-and-forth with the Secret Service to come up with a design for prop money that the feds felt comfortable with. That kind of guidance isn’t something they normally provide, but Rappaport managed to finagle an exception.

Rappaport notes that fake money is such a hassle that there’s really no real money in it, so to speak — “It’s not a big moneymaker, no joke intended.” But he provides it to clients, knowing they’re going to come back for other props that will earn a profit.

TV and movies are full of characters who come across suitcases full of cash. It’s a fun plot device—what will the characters do with all this easy money? What would it be like to hold it all? But behind all this cash is someone like RJ Rappaport who has been through a meticulous design process and years of back and forth with the Secret Service. Because for the film producers, there’s just no such thing as easy money.

Comments (4)

Share

I would love to know the song used at time marker 5:54 in this episode. I tried to see if it was from one of the videos or listed in the credits but didn’t find it. Is there a place to find this info for future reference?

Nevermind! Figured it out. For anyone else who’s curious the song is:

Walk On By – Isaac Hayes w/The Bar-Kays (1969)

But it would be nice to have a tracklisting of songs used in your podcasts if that’s not asking for too much (and if you don’t have that stored somewhere already)! :)

Meditation is one way a new player can channelize his feelings and pay attention to the game.

Fascinating episode. I had no idea about the origins of the Secret Service. I would be curious to know how their duties expanded outside the Treasury Department to now guarding POTUS.