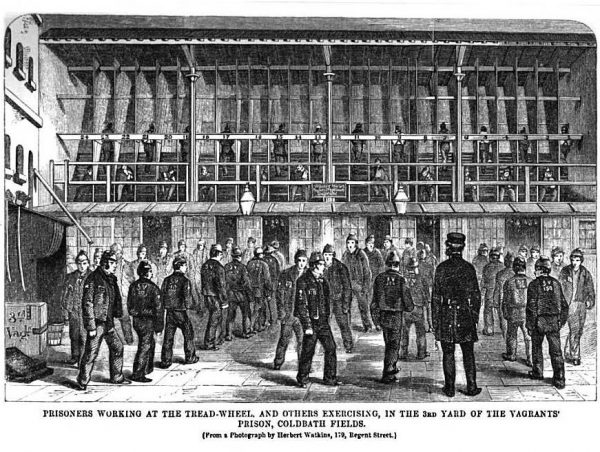

English engineer Sir William Cubitt’s “tread-wheel” was not exactly a new invention, but its dark application was novel. It was engineered to occupy and exhaust prisoners who were forced to endlessly walk over a cylindrical device. At the same time, it was not strictly punitive. As the inmates hiked for eight-hour stretches effectively scaling thousands of feet per shift, the mechanism could pump water or crush grain.

Its inventor argued that the device could be useful in “reforming offenders by teaching them habits of industry.” Prisons across Britain and the United States bought the sales pitch and the machines. In the early 1800s, a New York prison guard saw things a bit differently, opining that the device was quite punishing indeed, and specifically that it was tread-wheel’s “monotonous steadiness, and not its severity, which constitutes its terror.” Over time, many wardens transitioned to other, more labor-intensive tasks like breaking rocks and building structures. By 1895, there were 39 treadmills in English prisons, but sales peaked and their use was abolished in Britain by the 1902 Prisons Act.

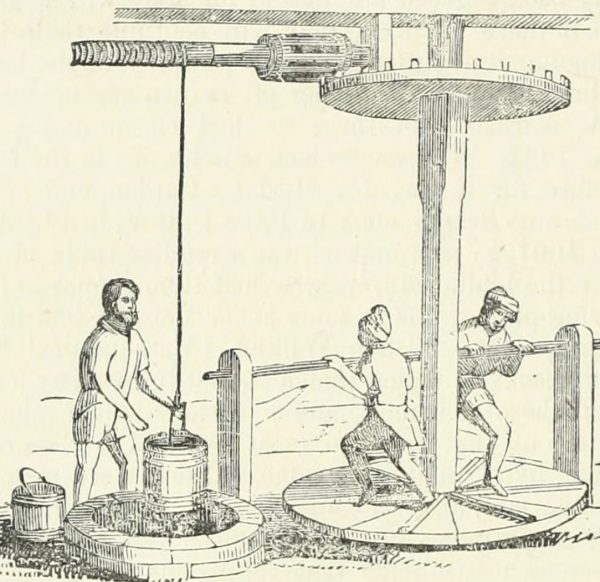

Cubitt’s designs were new, but they built on ancient precedents. Since Roman times and through the Middle Ages, treadwheel cranes had been used to build grand structures like castles and cathedrals, turning human motive power into pulley lift systems. Mechanical advantages built into the design of particularly efficient versions could allow a single person to lift thousands of pounds. Such devices could be used to hoist building materials or lift heavy cargo onto and off of ships.

Over the centuries, treadwheels have come and gone, assembled in different ways at different times as well as used to build cities and punish lawbreakers, but the basic mechanical ideas have remained largely the same — no sense in reinventing the wheel.

Now, of course, electrical treadmills are popular exercise devices and have evolved all kinds of curious offshoots, like climbing wall variants. The biggest shift in their design, though, was the reversal of roles — power is consumed, not generated, by people using contemporary treadmills. While arguably punishing, they are voluntary.

Comments (2)

Share

There was a treadmill at the Port Arthur convict settlement in Tasmania, Australia. They built a flour mill which was initially intended to be powered by a stream, but when the water flow proved insufficient to power the mill, they used convicts instead.

Unlike the New York prison guard’s comment, I’ve heard that the wheel in Port Arthur was quite physically demanding to operate and the consequences of slipping/succumbing to exhaustion and falling through the gap were terrifying.

https://portarthur.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/Port-Arthur-Penitentiary-Guide.pdf

Whenever I see things about ancient trade system and their work life. It always reminds of latest tv show peaky blinders which clearly presents how it was during olden days. Thanks much for the article.