Looking up in a city, you may notice that many buildings step back as they get higher, or are set back from sidewalks to create open spaces on the ground. While not unique to New York, the effect is particularly pronounced in the Big Apple’s densely packed street canyons. The shape of some classic NYC towers, like the Chrysler Building, can make it seem like setbacks are aesthetic design decisions, but in reality, they reflect a highly specific, city-shaping ordinance dating back to 1916.

The Equitable Building is sometimes cited as the proverbial straw that broke the camel’s back, but this structure was more accurately the canary in the coal mine, signaling rather than leading to the end of space-maximizing skyscrapers — structures filling out their lots and rising straight up into the air. Completed in 1915, it was the latest in a growing number of such structures, with two sections cut out (making its plan view into an ‘H’ shape ) to allow some daylight access for central occupants of this dense architecture.

The Equitable Building is sometimes cited as the proverbial straw that broke the camel’s back, but this structure was more accurately the canary in the coal mine, signaling rather than leading to the end of space-maximizing skyscrapers — structures filling out their lots and rising straight up into the air. Completed in 1915, it was the latest in a growing number of such structures, with two sections cut out (making its plan view into an ‘H’ shape ) to allow some daylight access for central occupants of this dense architecture.

This structure and buildings like it were relatively unconstrained at the time, leading developers to take full advantage of every square inch. As they grew taller, however, more and more citizens expressed concern about the shadows they cast on adjacent structures and the ways in which they loomed up over and choked off the streets below.

Even before the Equitable Building was finished, momentum had been building in the direction of restricting this kind of architecture, culminating in a new mandate the year after it was completed.

New York’s 1916 Zoning Resolution was the first citywide zoning legislation in the US. It would go on to shape the Manhattan skyline but also to spur subsequent municipal and national zoning rules.

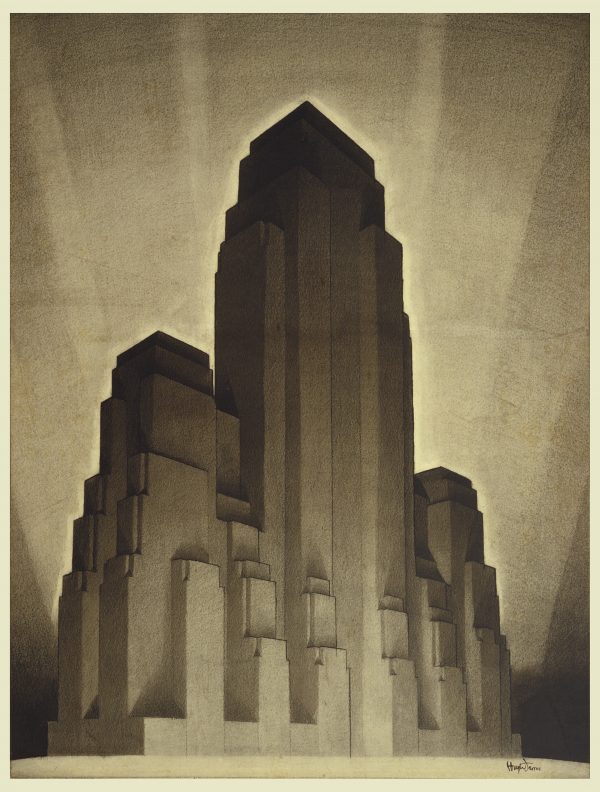

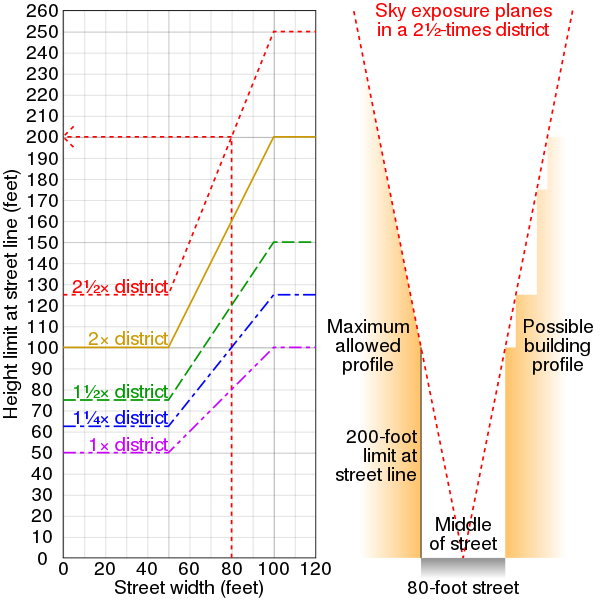

Simply put: developers who wanted to build higher also had to step their buildings back as they went up. This resulted in a lot of buildings that conform quite neatly to the laws of the land, their overall massing a direct result of tower designers maximizing space within new limits.

For New Yorkers at the time, the new rules worked out largely as promised, providing more light and fresh air on the city streets below. Architects in other cities followed suit, even in the absence of setback rules, taking stylistic cues from Manhattan’s cutting-edge towers.

Over time, modifications were made to the original rules, allowing designers to build higher, for instance, if they left more open space at street level. Many somewhat bland public plazas in front of blocky mid-century Modernist buildings can be traced back to these adjustments in regulations, though the utility of such plazas has been much debated.

Architecture is a product of design, but also of constraints. Setbacks not only shape the experience of city life, but can be used to date structures to different periods. Key moments in the history of zoning can be inferred from the outlines of buildings both in and beyond New York City.

Leave a Comment

Share