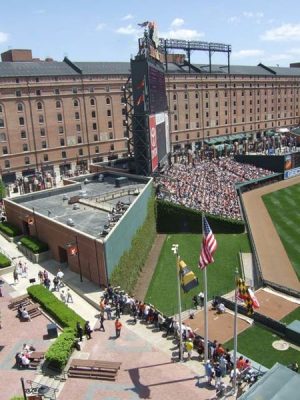

In 1992, the Baltimore Orioles opened their baseball season at a brand new stadium called Oriole Park at Camden Yards, right along the downtown harbor. The stadium was small and intimate, built with brick and iron trusses—a throwback to the classic ballparks from the early 20th century. It was popular right from the start. “It’s magnificent in an understated, baseball-only, real-grass, open-air, quirky, cozy, comfortable, cool sort of way,” wrote Tim Kurkjian in a glowing Sports Illustrated review.

No one knew it at the time, but Oriole Park at Camden Yards would change the design of ballparks all around the country. Its success set off a building boom in baseball, as city after city built new stadiums based on the architectural principles laid down in Baltimore. That design revolution would fundamentally change the experience of going to the ballpark and the relationship between baseball and cities.

From Urban Ballparks to Concrete Donuts

In the early 1900s, most baseball stadiums were relatively small and built in dense urban neighborhoods, which shaped their design.

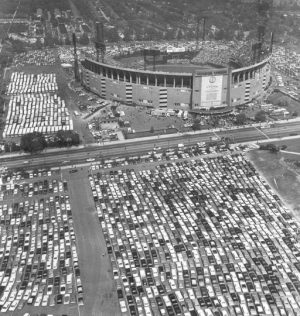

But in 1950s and 60s, as white populations fled downtown for the suburbs, baseball followed them. Teams built stadiums on the edge of cities where they were more accessible to middle class fans who drove to games in cars.

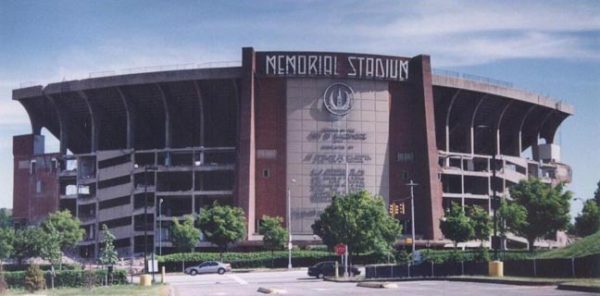

These massive new, multipurpose stadiums were designed to be house both baseball and football. They were set apart on large plots of land, often surrounded by acres of parking — completely different from their urban predecessors.

But these multipurpose stadiums, or “concrete donuts” as they were sometimes called, really weren’t great for fans of either sport. They were perfectly round to fit both a football field and a baseball diamond, but that meant that the seats were often really far away from the action, or angled in weird directions. They were also really large for baseball, with 50,000+ seats (versus 25-30K for urban parks), which left them looking big and uniform while feeling empty and impersonal.

The S-Word

For a long time, the Orioles played in their own concrete donut, Memorial Stadium, along with Baltimore’s football team, the Colts. When the Colts left for Indianapolis (citing Memorial Stadium as a reason), many began to fear the baseball team might also “leave town for greener ballparks,” says Larry Lucchino, who was President of the Orioles in the late 1980s. The team’s owner Edward Bennett Williams wanted to build a nice new multipurpose stadium — with that, the city could try and court another football team back to Baltimore. But Lucchino had another idea:

“Let’s look at the most successful baseball franchises out there. The Yankees in Yankee Stadium. The Cubs in Wrigley Field. The Red Sox in Fenway Park. And what did they have in common? They all played in a baseball-only facility, a facility that was designed for baseball and did not compromise architecturally for other other sports.”

Those ballparks were old and idiosyncratic, and Lucchino argued that a new ballpark could carry on that tradition and aesthetic — “an old-fashioned traditional baseball park with modern amenities,” he recites. “If we used that phrase once we used it ten thousand times.” He was so committed to this idea he banned Orioles employees from using the word “stadium” and collected fines when people said the “s-word” around him.

The new ball park would be built right downtown. This was seen as a way to revitalize downtown Baltimore, and the team managed to secure public funding. The Maryland Stadium Authority hired architects from Populous (known at the time as HOK Sport) to work with the Orioles own design director, Janet Marie Smith.

It was Smith’s job to ensure that the team stayed true to Lucchino’s vision of an old fashioned park. One of her key observations was that older ballparks were wedged into tight urban environments, and shaped by surrounding structures. Each ballpark had different dimensions, depending on the plot of land on which it was built. In most sports, the playing field is completely standardized, but not baseball.

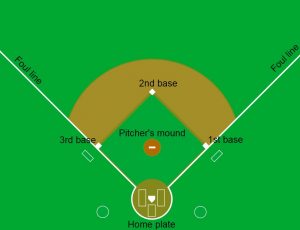

A baseball field drawn roughly to scale with minimal labels by Cburnett (GFDL)

“There are rules about the infield,” Smith explains.”You’ve got to have 90 feet between the bases 60 feet six inches from home plate to the pitcher’s mound. But there’s no rule about the outfield.” This fact led to a lot of irregular shapes and dimensions. That variety means that some ballparks are better for pitchers while others are better for hitters. Some parks give up more home runs to right-handed batters, others to lefties, and so forth. “The park itself really does shape the outcome of the game,” says Smith.

To make the new ballpark fit the neighborhood, they decided to leave an old abandoned brick warehouse in place and shape the field around it. This choice ended up informing the rest of the design, right down to the shape of the stands and the construction materials (brick and iron).

Attendance at games shot up in the new stadium. In their first two seasons at Camden Yards, the Orioles had the second-highest attendance in the major leagues. Pretty soon other teams started to take notice and they sought to emulate Baltimore’s success.

In 1994, another old-fashioned baseball-only ballpark called Jacob’s Field opened in downtown Cleveland. And that was just the beginning. Pretty soon, all new ballparks were being designed to look like old ones.

In the 25 years since Camden opened there have been 20 new stadiums built, and there is not a concrete donut in the bunch. Like Camden Yards, most of these new stadiums have been built close to city centers — and most have been paid for in part with public money.

Cities were sold on the idea that downtown parks would be a boon for everyone involved. “Here’s something that’s supposedly a win-win-win,” explains Neil DeMause, a journalist who studies stadium economics. “It’s a win for the team because they get you know new revenue. It’s a win for the fans because they get a stadium that they love, and it’s a win for the city because they get to revitalize a district.”

But it’s not clear that building a baseball stadium is the best way to revitalize a neighborhood — most local businesses can’t rely on baseball crowds showing up for 81 games a year. And then there is the question of whether the public should have to pay for privately owned buildings. Sports may be important for city identities and fans, but teams are still businesses — owned by very wealthy individuals.

Greener Ballparks

Difficult questions about function and funding have not, however, stopped the retro ballpark building boom. Across the country, baseball teams have done everything they can to follow the Camden template. They even go to the same architecture firm, Populous (formerly known as HOK Sport).

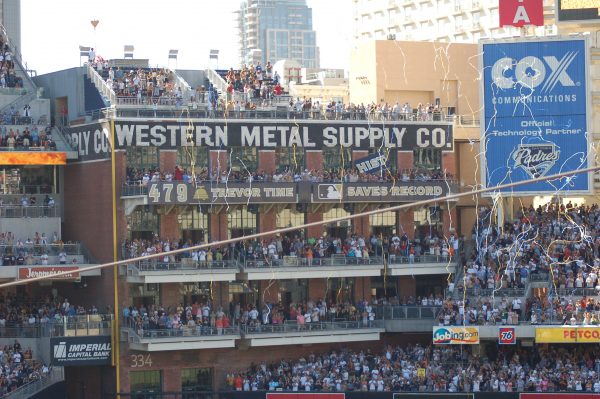

These new Populous ballparks are small and old fashioned-looking but they also feature modern amenities—comfortable seats and fancy foods. And while designed to be different, they tend to follow a similar aesthetic format, featuring a lot red brick and green-painted iron. These new parks also feature asymmetrical playing fields, which are in many cases dictated by the surrounding cityscape.

San Diego’s Petco Park, for instance, has a left field line informed by the adjacent Western Metal Supply Company — the team just painted a yellow stripe down the corner of the warehouse in lieu of a foul pole.

AT&T Park in San Francisco is squeezed right up against the San Francisco Bay and the right field line goes all the way to the water. This gives fans a spectacular view while creating a unique local drama: splashdown home runs. When someone hits a ball into the bay, a flotilla of kayakers descend on the souvenir.

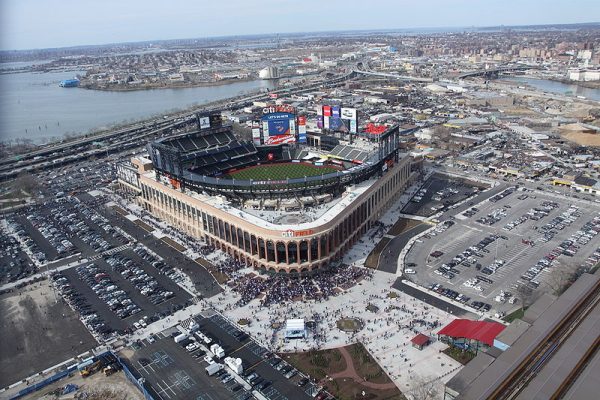

But not all of the new retro ballparks are so successfully integrated with their urban context. While Citi Field (the new Mets Stadium in Queens) has an asymmetrical shape, it was artificially derived. Its odd dimensions don’t respond to facets of the built environment.

Examples like that illustrate just how much the Camden template itself has become dominant over the ideas that drove it in the first place, like: creating something specifically fitted to a given city. Mark Lamster, Architecture Critic at the Dallas Morning News, is critical of this new orthodoxy. “They all have the same DNA, they all kind of look kind of the same, except the whole idea is that each one is idiosyncratic and individual. It’s a tall tale.”

But he also concedes these retro stadiums are better than the concrete behemoths that came before them. Citi Field may be a bit derivative, but Lamster still thinks it is better than what came before.

Asked to describe its predecessor, he says: “Yes I can describe Shea Stadium. Think of a toilet. Put seats in it. That’s Shea Stadium. Was it a nice place to watch a game? No. Is the new place a nice place to watch the game? Absolutely! It’s a much much nicer place to watch a game. It’s a really great place to watch a game.”

And being a nice and familiar place to watch a game is important for baseball. Even as television ratings have started to slide in recent decades, attendance numbers are strong — people enjoy going to the ballpark. And part of that is tied to tradition, that nostalgic experience of sitting in the stands, eating a hot dog and listening to organ music.

Baseball’s obsession with history and tradition helped drive the retro ballpark revolution. But, as an architecture critic Mark Lamster is ready for some team out there to embrace the future: “Why were we looking backwards when we designed these ballparks instead of looking towards new materials, and new ways of building, a new architecture?”

And if Camden Yards taught us anything, it’s this: when someone does come up with a great new way of building a ballpark, every team in the league is going to want one of their own.

Comments (14)

Share

As a baseball fanatic, I absolutely love this episode. At the end, you mentioned the idea of a new style of architecture for baseball parks. I certainly agree with the sentiment, but there was no mention of Marlins Park, which was built in 2012 in a contemporary style. While I’m not necessarily a huge fan of the design (nor do I dislike it), it is a model that future stadiums can follow. As a side note, though, the newest stadium in Atlanta does have the classic design to it. Read from that what you may…

+1 I also thought this was a strange oversight.

I agree, a huge oversight. The podcast ends with a statement about looking forward, a new architecture, but nothing about Marlin’s Park. Why?

It’s mentioned in the episode that Camden Yards was the first urban baseball stadium built in decades, but as a point of local pride, Toronto’s Skydome (now Rogers Centre) beat it by 3 years. Admittedly, the Skydome is still a concrete bowl (with a lid) with room for 50,000, but it’s a transitionary step. At the very least, its site was chosen for proximity to transit, and to revitalize the downtown core, although on a big enough piece of land it wasn’t shaped by the site.

Anyone interested in learning more about how this revolutionary ballpark came to be should read “Ballpark: Camden Yards and the Building of the American Dream”. A lot about the park seems obvious in retrospect, but there were significant difficulties getting it built.

As mentioned in the story, a lot of area residents were really mad that they weren’t building a facility which would accommodate football, because people were still stinging from the Colts leaving only a few years prior and believed that a new team would not want to move into the rapidly aging Memorial Stadium. Also, at the time, the process of the Inner Harbor area becoming the go-to place in Baltimore was still in its very beginning stages (the nearby Convention Center and Aquarium had only opened in 1979 and 1981, respectively), so placing the park where it is was not the no-brainer it seems to be now.

There’s also a significant controversy over the role of an architect named Janet Marie Smith. Some have downplayed her contributions to the park’s design, while others claim she was responsible for the decision to preserve the B&O Warehouse (many don’t know the building had been prepared for demolition before they decided to save it) and has been a victim of sexism in architecture.

Really nice job on this story, and there is a lot more to dig into about this remarkable building.

Coors Field, in Denver, is built in the same style as Camden Yards. It has completely revitalized the ‘Lo-Do’ neighborhood and even expanded the urban fabric in the area. It’s a unique example where the urban fabric actually grew toward the stadium and arguably became an extension of downtown.

The Denver Post recently wrote about how Coors Field has influenced the economics and design of the surrounding neighborhood. It’s a great follow up to this post at takes a solid in-depth look at the last 25 years of a successful retro ballpark. (Go Rockies!)

http://www.denverpost.com/2017/06/04/lodo-resurgence-coors-field/

True, it did create it’s own neighborhood, a hipster expensive one. But unfortunately, Coors Field is so boring and other than the purple “mile high” seats, unremarkable. In my opinion, it’s overpriced for how lackluster the team is.

“Why were we looking backwards when we designed these ballparks instead of looking towards new materials, and new ways of building, a new architecture?”

Because architecture, like many other arts (painting, sculpture) has been in vapor lock for about a century. So there isn’t a choice between “new” architecture and “nostalgic” architecture… The only choice is, which variety of nostalgic architecture do you prefer?

(BTW, my preferred email uses a .photography domain, which your form bounces out. Tsk, tsk. New gTLDs have been out for two years already, folks.)

In fact, I’ve come up with a measure of this, called the Expo 67 Test:

http://halobrien.com/2012/11/27/the-expo-67-test/

=============

Or there’s this piece of mine, “Looking Dated.” It shows a 1927 ad for Mercedes Benz, with a car and model out front of a Le Corbusier building.

The fashion looks dated because fashion moved on.

The car looks dated because industrial design moved on.

The architecture doesn’t look dated because architecture hasn’t moved on.

http://halobrien.com/2013/11/17/looking-dated/

I always enjoy the podcasts, but especially enjoyed this as have been to 27 MLB ballparks and almost all of the stadiums mentioned in this podcast. Though only a few of the cookie cutter parks.

One thing that frustrates me, is everyone categorizes Target Field in the throw-back category. Yes, it is designed by Populous, and has some historical elements like the big old Minnesota logo in center. But to me I have always thought it was the first post-retro park. I really liked it and think it is a forward thinking design. Here are a few shots:

http://populous.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/TargetField-Minneapolis-UrbanConnection.jpg

http://populous.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/TargetField-Minneapolis-LeftFieldView.jpg

http://www.mortenson.com/~/media/images/projects/sports%20and%20event%20centers/target%20field/targert-field-4.ashx?h=451&la=en&w=680

I really enjoyed going to a game there, and felt it was a modern feeling park.

I was delighted to hear this this podcast about Oriole Park at Camden Yards (OPACY) in Baltimore. I have been a fan of this podcast for years and have sought out locations including the Winchester House because of your stories.

As I’m sure you found in your research about Oriole Park at Camden Yards, the current Oriole Park is actually the 6th, depending on how you count it. I am proud to be affiliated with Peabody Heights Brewery, which sits on the site of Oriole Park V.

An original wall still remains from the fire that burned the stadium down.

Thank you for sharing a piece of Baltimore. We still like you Roman, even though you would move to Pittsburgh first.

http://www.mdhs.org/underbelly/2014/10/02/lost-city-the-burning-of-oriole-park/

http://ghostsofbaltimore.org/2015/05/15/why-is-it-named-oriole-park-at-camden-yards/

http://www.davidbstinsonauthor.com/tag/peabody-heights-brewery/

http://www.peabodyheightsbrewery.com/

Great episode. I nodded along the whole time.

A nice detail might have been to include New Comisky Park now called-Guaranteed Rate Field- (aweful!) Was created by the same firm that made Comisky. It was not well received and has undergone a lot of renovations. Having worked there for a summer a couple years after it was built, it is in a completely different and lower category than the newer that came after.

Also, the New Yankee Stadium is awful…but that deserves a whole other show.

Take care and Roman, you are an inspiration. Inspired by you to start my website!

As a fan who visits OPACY 15 to 20 times a season (since it opened in 1992) I’ve never grown tired of the park and I’ve never taken for granted the beauty of watching a game there. I’ve been to many parks and while PNC and Safeco are great parks, OPACY will always be the first and finest of the modern parks.

This is such a good testament to the greatest ballpark ever. There’s nothing like walking into Camden Yards and seeing the field before you. It’s a holy experience if you’re a baseball fan. There’s not a bad seat in the house from the rooftop deck to section 336 in the uppers behind home plate. It’s simply gorgeous. I am in emotional pain right now on this lovely day in May of 2020 deeply missing being able to be at Camden Yards to watch the Baltimore Orioles play a game of baseball.