Imagine being able to plant things in your garden that would normally never grow in that climate, outdoors and without any electricity. Architects and urban designers often factor thermal mass into their designs, employing materials that absorb heat by day and release it at night to help warm human occupants. And though we rarely see it today, that same strategy has been used in agriculture for centuries. Given how much energy it takes to operate greenhouses, designers and engineers could learn a lesson or two from this inventive tradition.

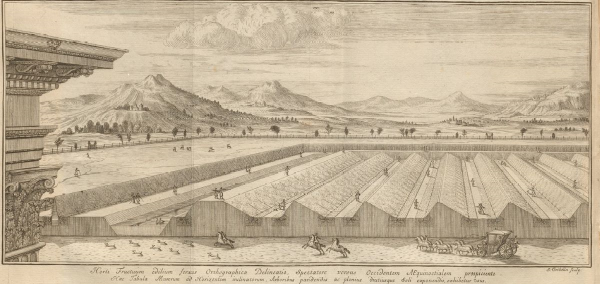

As early as 1561, a Swiss botanist named Conrad Gessner observed the effects of heated walls on fruit growth. Walled plots not only gained shelter from wind and animals but also heat from the sun, creating more stable local micro-climates and fending off frost. This was useful to farmers seeking to grow sensitive crops further north. In hindsight, it was also helpful in light of what has since become known as the Little Ice Age, a period of cooler global temperatures starting in the 1600s.

Thermal “fruit walls” grew increasingly popular in the 1600s, enabling urban farmers to grow “Mediterranean fruits and vegetables as far north as England and the Netherlands, using only renewable energy,” reports Kris De Decker of Low Tech Magazine. Absorbing solar heat by day, these masonry walls were able to raise temperatures by as much as 10 degrees Celsius (18 degrees Fahrenheit) at night.

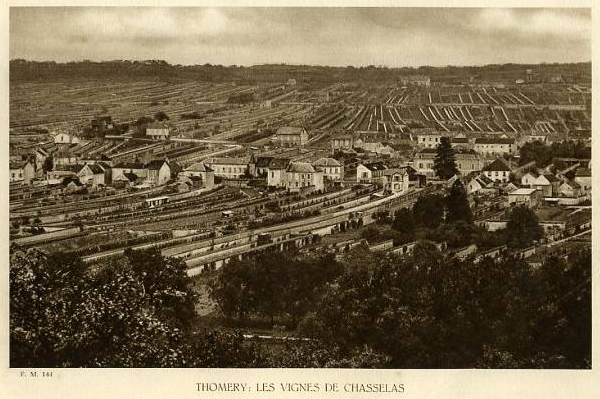

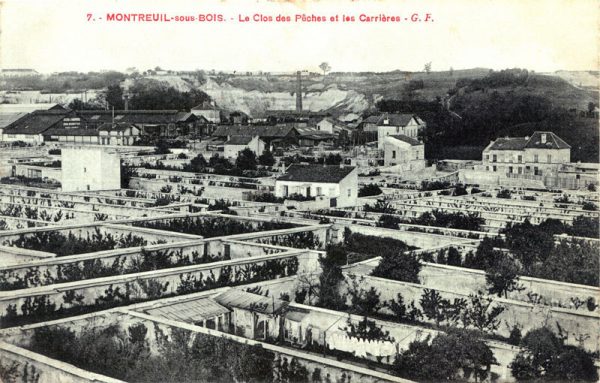

Over the years, walled gardens flourished in places like Montreuil, a suburb of Paris, which had hundreds of miles of fruit walls for peaches by the middle of the 19th century. Per Decker, “the 300 hectare maze of jumbled up walls was so confusing for outsiders that the Prussian army went around Montreuil during the siege of Paris in 1870.” Areas like this with adjacent plots also benefited mutually from proximity, sharing warm walls that effectively created larger micro-climates.

The Dutch, meanwhile, began to develop curved varieties that could capture more heat, increasing thermal gain (particularly useful for a cooler and more northern region). The curves also helped with structural integrity, requiring less thickness for support.

Further north in Britain, these wavy variants became known as crinkle crankle walls (an old-fashioned way of saying zig-zag). The English also innovated further on flat walls, piping hot air (or water) through “hot walls” to combat even cold temperatures. Like ultra-slim brick houses, these heated walls featured chimneys on top for exhaust purposes.

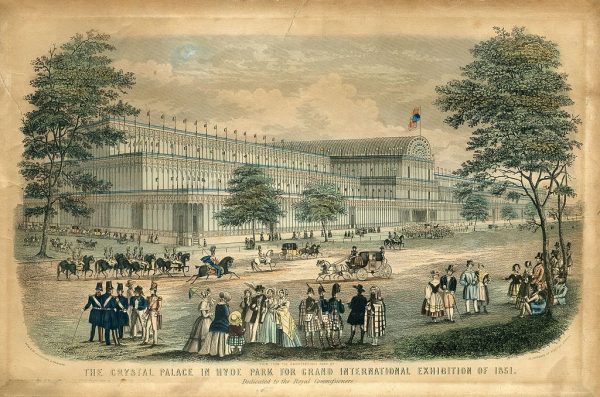

As energy became cheaper and glass easier to construct, a kind of proto-greenhouse began to emerge. At first, panes of glass were leaned against existing garden walls, allowing in daylight while helping reduce heat dissipation. This design then gave way to the fully-glazed structures we still see around the world today (which also echoed a shift from masonry to metal-and-glass construction in Modernist architecture). Greenhouses were easier to maintain and benefited from lower energy costs as well as innovations in modular design and mass production, but unlike fruit walls, their energy use is far from passive.

Decker reports that “crops grown in heated greenhouses have energy intensity demands around 10 to 20 times those of the same crops grown in open fields. A heated greenhouse requires around 40 megajoules of energy to grow one kilogram of fresh produce, such as tomatoes and peppers.” This puts greenhouse agriculture on par with meat production in terms of energy use, raising a key question: can designers of today take lessons from a long history of garden walls?

Comments (5)

Share

In Pantelleria there also are similar walled gardens, these structures are circular and aim to protect the trees from strong year-round winds blowing on the island.

https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Giardini_panteschi

Colonial Williamsburg in Virginia has several walls in which fruiting trees have been espaliered (Stretched flat) against them. I can’t help but wonder if that is part of this tradition.

It also had to help that stretching a plant flat against a surface like this also assists in collection of the fruit and the tending to the budding stems, similar to grape vines which are trained to grow in rows.

Very interesting!

But to say that this is “without any electricity or technology” neglects that this clever use of walls is certainly a technology, despite the lack of fancy knobs and buttons ;)

…looks like you changed the wording, thanks!

I wonder whether this technology could be tweaked to help plants grow in places that are normally to HOT for them. Perhaps strategic placement of shade…..