As far back as the 13th century, a powerful principle has informed the legal notion of property ownership — in Latin, cuius est solum, eius est usque ad coelum et ad inferos, or in English: “whoever’s is the soil, it is theirs all the way to Heaven and all the way to Hell.” The idea is intuitive but potent: a property owner is entitled to an infinite vertical column of space defined by the horizontal boundaries of their estate. On this principle, one owns land as well as everything above and below.

The strict formulation of ad coelum was solidified in English common law in the case of Bury v. Pope in 1587, when one property owner was held to have the right to build up against the window of his neighbor: “And lastly, the earth hath in law a great extent upwards, not only of water as hath been said, but of aire, and all other things even up to heaven, for cujus est solum ejus est usque ad coelum, as it is holden.”

Still, England has evolved exceptions over time. Now, “Ancient Lights” can be preserved — Right to Light laws prohibit the obstruction of windows with a 20-year history of light access. These laws date back to 1663, but their current form is based on the Prescription Act of 1832.

As the evolution of English light access laws illustrates, nothing lasts forever — and this idea of ownership based on vertical infinity was bound to face challenges eventually. The rise of new technologies and cities, including the advent of air travel and subway systems, have continued to reshape and erode this idea over time. The heaven-to-hell principle (often abbreviated to ad coelum) has been influential but also chipped away at incrementally in the centuries since it was coined.

Up in the Air

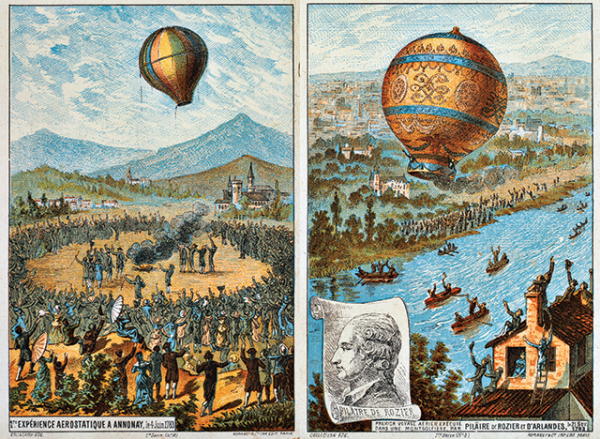

When the first hot air balloon took to the skies in 1783, people began to realize that ad coelum could lead to absurdly trivial trespass violations when a traveler simply passes over someone’s land.

As plane travel began to take off in the United States, ad coelum was incrementally reduced by the government through things like the Contract Air Mail Act of 1925 and Air Commerce Act of 1926. Slowly, the idea of high-up airspace as a “public highway” emerged.

Then, in 1946, United States v. Causby put a definitive end to the idea of infinite aerial ownership. For Lee Causby, a farmer whose chickens were literally being scared to death by low-flying military planes, it was a victory — he was compensated for flights that had passed over his property below public airspace altitudes (365 feet). The Supreme Court concluded that the government can’t own all airspace (down to the ground). But their ruling also stated clearly that ad coelum “has no place in the modern world.”

Then, in 1946, United States v. Causby put a definitive end to the idea of infinite aerial ownership. For Lee Causby, a farmer whose chickens were literally being scared to death by low-flying military planes, it was a victory — he was compensated for flights that had passed over his property below public airspace altitudes (365 feet). The Supreme Court concluded that the government can’t own all airspace (down to the ground). But their ruling also stated clearly that ad coelum “has no place in the modern world.”

Zoning laws and “air rights” regulations vary from place to place but also limit the heights of buildings, especially in cities.

Space travel represents an extreme example of how owning an infinite upward column necessarily fails when taken far enough. On a spherical and rotating planet, the idea is naturally absurd — ownership of space would be constantly changing. Independent of ad coelum, the 1967 Outer Space Treaty affirms that “outer space, including the moon and other celestial bodies, is not subject to national appropriation by claim of sovereignty, by means of use or occupation.”

The specifics of lower-altitude overflight rights, though, have continued to change and evolve, with different rules for different heights. The advent and popularity of drones in particular has resulted in a number of cases that are still reshaping airspace rights law today.

On the Ground

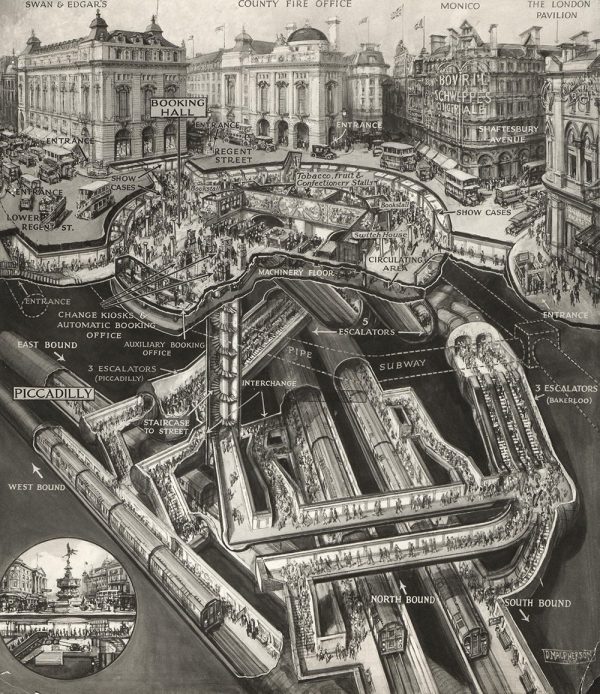

Back down on (and under) the ground, the ad infernum idea within ad coelum has been similarly challenged and limited — as in the air, the further from the surface the less likely it is to hold. Subways, deep drainage tunnels and particle colliders have, among other things, been deemed to be deep enough not to deprive surface owners of value. In 1931, for instance, US court rules that a sewer located 150 feet deep was not on land belonging to the home owner above. Still, approaching the surface from those more distant depths, things can get tricky.

There are mineral rights, for instance, which can apply to fuel sources (coal, gas and oil), precious and industrial metals (gold, silver, copper, iron) and other resources (salt, limestone, gravel, etc.). In many places, these can be bought and sold independently of surface rights.

Then there are littoral rights that can extend outward for properties adjacent to bodies of water, like an ocean, bay, delta, sea or lake. In most places, there are allowances for usage and enjoyment tied to low or high water lines (beyond which the waters are public).

Meanwhile, riparian rights deal with water that flows through properties, like rivers. Small bodies generally limited to “reasonable use” but with various potential restrictions (to protect watersheds, for instance). Larger ones are usually treated like public highways. The details get complex fast, because interest in these moving waterways is shared by so many parties beyond a given property owner, including cities, states and other owners downstream with their own rights.

While these various surface and subsurface rights have evolved over time, they can still lead to strange sources of contention. Even rights to water falling freshly from the sky can be problematic — while it may not be groundwater yet, rain does have that implicit potential. In some cases, laws are in place against rainwater harvesting because it is viewed as violating the water rights of those downstream. In Colorado, for instance, the question of harvesting and using rainwater was debated for years before a determination was made: property owners can store up to 110 gallons in barrels for outdoor use only.

Comments (1)

Share

This is such a cool story. As someone who works on the fringes of land ownership rights I thought this story was fascinating. I’ve always been confused on the balance of the split estates though. How much of your surface rights can I imped on to get to my mineral rights? What about subsidence from collapsed mines?

Thank you for writing this and I look forward to reading the following article.