Architectural acoustics is a field that rarely makes the front page of any newspaper, much less op-eds in tech publications like Wired. The January 11th opening of Herzog & de Meuron’s Elbphilharmonie, though, was such big news that even my architecturally naive family heard about it, and let’s just say: that is a feat. Everywhere I go, friends and acquaintances who know I study acoustics ask me: “What do you think of that new concert hall in Hamburg?” What they don’t realize is that there is a larger force at work — a unifying individual behind the scenes of this and other famous concert halls who is not an architect at all. But we’re getting ahead of ourselves — back to Hamburg.

The Storyline of a Starchitect’s Hall

The Elbphilharmonie (called the Elphi by the locals) follows a familiar storyline for concert halls in the age of Starchitecture, a pejorative (yet sometimes endearing) term describing an ongoing trend: hiring (in)famous architects–such as Frank Gehry, Herzog & de Meuron, Jean Nouvel, and Santiago Calatrava–to design highly dramatic and idiomatic buildings, often for cultural centers, museums, and yes: concert halls.

The story generally unfolds as follows: a large city has a need for a new concert hall and selects a major architect who develops a stunning and structurally ambitious design, with a low price tag that is rarely realistic.

The building ends up being so ambitious that it goes significantly over the budget. Attempting to rein in the budget (aka “value engineering”) leaves the project either stripped down or very late or both.

The idea of the concert hall becomes unpopular, and is protested by members of the public, who often foot the bill. The hall is constructed, and it is either beloved or rejected, though rarely is it an acoustical failure. Often if a new concert hall fails, it fails architecturally.

The Risky Architecture of Concert Halls

The father of this trend in concert halls is, of course, Frank Gehry, who designed the Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles, California. The project began in 1988 and was not completed until 2003. At the time, it was the most expensive concert hall ever built.

Final design work officially started in 1994 and reached a funding crisis in 1997. Fortunately, the project was saved by an injection of capital from Diane Disney Miller, Walt Disney’s daughter. Still, the project took six years to construct. It has been reviewed favorably by many, and is cherished both by residents and visitors alike.

In 2007, the National Center for the Performing Arts by French architect Paul Andreau opened in Beijing, China. Subsidized by the government, the project cost a mind-boggling 3.2 billion yuan (about half a billion in US dollars). To put that in perspective, when the cost is averaged out, each seat required around $70,000. The water and electricity for the building’s exterior cost millions of yuan each year alone. The Chinese government has determined that the project will never be profitable, and continues to subsidize over 60 percent of the operations.

Fast-forward two years to 2009: Gehry’s LA budget record was bested by French architect Jean Nouvel, whose Koncerthuset in Copenhagen cost $300 million. Though completed on time, it ended up running three times more than the original budget. The ballooning expenses caused angry recriminations, ultimately resulting in the cutting of 500 staff positions (seven of whom were performers in the Danish National Symphony Orchestra) simply to make ends meet. The hall has been reviewed favorably, and ten years later is still held in high regard by both concertgoers and musicians alike.

The great recession put a temporary moratorium on huge public works projects by major architects. Several concert halls were constructed during this time, notably those in Finland and Iceland, but these generally employed local architecture firms rather than international stars. The mega-hall concept seemed dormant, with one notable exception: the Paris Philharmonie, announced in 2006. In 2007, Jean Nouvel was again selected as the architect.

What would follow was one of the most dramatic stories in the history of concert halls. Finished in 2015, the hall ran two years late and cost three times its original budget, as is tradition. However, the story takes a much more dramatic twist.

Jean Nouvel promised it would be one of the most remarkable symphonic spaces in history, and he wasn’t wrong. The budget, fighting over the budget, the delays, and the fighting over the delays resulted in what can only described as a 505 million-dollar mess.

In a fit of architectural dramatic rage, Nouvel himself abandoned the project, denying that it was his fault the building was overdue and overbudget. He boycotted the hall’s opening, saying that the project “wasn’t finished.” Nouvel went so far as to pen an editorial in Le Monde, claiming that the architecture was “martyred” and “sabotaged” by his clients, and therefore his name could not be attached to it until changes were made. This later turned into a lawsuit, which he lost.

Nouvel was right about one thing: the hall was unfinished: On its opening day, workers were still frantically putting the finishing touches on the exterior. As a final blow, critics panned the architecture. The Guardian’s Oliver Wainwright called it: “…a greatest-hits mash-up of dictators’ icons, a building that blends the excesses of ‘starchitectural’ culture into one over-seasoned potage.”

The Paris Philharmonie, previously the world’s newest and most adventurous concert hall, left a bad taste in the mouths of the public with regards to gargantuan cultural projects helmed by daring architects. However, despite all of this drama and the building’s aesthetic shortcomings, the acoustics were favorably reviewed by both architecture critics and classical music critics alike.

The Architect and the Acoustician

Contrary to popular belief, the architect is not the dictator of the interior design of listening spaces; rather, the interiors of concert halls, theatres, opera houses, and other venues are a joint venture between architect and acoustician. Sir Harold Marshall of Marshall Day Acoustics designed the acoustics for the Philharmonie de Paris, as well as its development over eight years in collaboration with the Ateliers Jean Nouvel. But Yasuhisa Toyota of Nagata Acoustics provided recommendations as Jean Nouvel’s personal consultant when the architect won the competition and he supervised the modelling studies.

Toyota has worked as an acoustician on the aforementioned concert halls not only in Paris and Hamburg, but almost every major and minor concert hall — including every contemporary hall mentioned in this article — since his breakout project, Tokyo’s Suntory Hall. Suntory, built in 1986, immediately became a case study for the field and a favorite of both musicians and concertgoers.

For Toyota and the rest of the field of architectural acoustics, high-budget, high-profile halls have been even more risky than they are for the architecture world. Some rewards come with those risks: these large budgets have enabled new acoustics solutions to be developed. The adventurousness of the architecture has proven to be a renaissance for acousticians, who are able to work with space in a more sculptural way, enabling a visual and aesthetic seamlessness between the acoustic treatment and the architecture. However, in the case of projects (like Paris) where the architecture is considered to be unsuccessful, the legacy of the project rests solely on the acoustician.

Concert halls have always been a risky business. The science and art of architectural acoustics itself is little more than a hundred years old. Before the turn of the 20th century, concert halls were built essentially by guesswork. Some, like the Musikverein in Vienna, sounded better than others, and questions were raised as to why. In the beginning, physicists like Wallace Sabine came up with mathematical formulas to explain certain acoustical phenomena, such as reverberation.

However, while these early mathematical models accounted for the size and materials of a space, they did not take into account the shape of the walls. As a result, concert halls were built with low ceilings and great widths between the walls (often in the shape of a fan), since this was less costly and still satisfied the mathematical metrics. But these halls were and remain unsuccessful, simply because they did not take room geometry into account. To be fair, the requisite tools had not yet been developed — the field did not really bloom until the age of digital technology, when complex computer modeling made it possible to predict what a hall would sound like before it was built.

It takes around fifty years for a hall to be designated a “good hall” or a “mediocre hall” or a “bad hall.” Why fifty years? Because by the fifty year mark, the hall has seen countless visitors, recordings, acoustical analyses and tests, and has been subject to a number of often contrasting opinions.

Only recently have we been able to designate the great halls of the mid-20th century, like the the revolutionary Berliner Philharmonie built in 1963 by Hans Scharoun, which set the precedent for many late 20th century and almost every major 21st century hall. The Berliner Philharmonie pioneered the concept of vineyard-style seating, wherein the orchestra platform is in the center, surrounded on all sides by audience seating.

The Rationale Behind the Risk

The first great concert hall of the 20th century was Boston Symphony Hall, built in 1900. Wallace Sabine, the father of the field itself, was the acoustician. Now the race is on for a project to be designated the first great concert hall of the 21st century, and the key to that prize lies not only in architecture, but in the technology behind it.

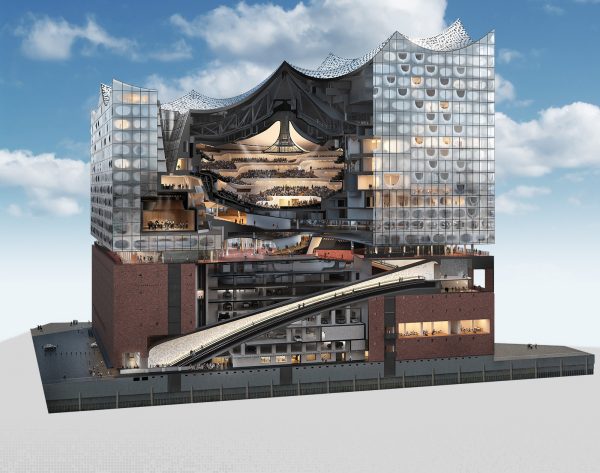

With every new project, the sophistication of concert hall acoustics becomes more and more advanced. In the case of the Elbphilharmonie, the walls are covered by 10,000 individual panels, each with its own pattern of cells extensively sonically modeled via new algorithms and fabricated using new techniques, previously impossible even during the era of Gehry’s Walt Disney Concert Hall.

It is difficult to say if the Elbphilharmonie will be on the shortlist for greatness, despite reports of musicians being moved to tears during its acoustical tests. For the fields of both architecture and acoustical design, however, its knocking the melodrama of Paris out of the public eye is a welcome relief. The studies used to fabricate the hall’s interior panels will provide a framework for understanding how deeply one can manipulate the sonic picture of a hall on a micro level. It seems that, in this case, the risk has paid off. Until next time, of course.

Comments (3)

Share

I am agog!! How could this article not mention the Sydney Opera House – the design and construction of which wrote the template the other examples in this article followed. And which occurred decades earlier than the earliest example given here. Everything. The signature startling design, the imported star architect (first hero, then villain, the outcast , then returned and forgiven prodigal) the waning and waxing of the public’s relation the building, the engineering challenges, the battle between artistic vision, acoustics and money. And oh the money – Sydney ran a public lottery for over a decade to pay for it.

I know Australia is not on everyone’s architectural radar, but I would have thought the Sydney Opera House was??

This article is for the most part historical – but if it want to be historically legitimate it needs a significant rewrite.

The sectional axonometric that you show a small pic of is one of the greatest architecure illustrations i’ve ever seen- here’s a link to it larger:

https://d3c80vss50ue25.cloudfront.net/static/images/background/house-infographics.jpg

I don’t always take a look at who’s the author of an article on a site such as this, even if I like it, because I’m no likely to remember anyway… (no insult intended by that, I swear…I just have very bad memory)

This time I did and was pleasantly surprised to see that the writer is no other that the author of my new favorite blog!

Hi Kate, great article, keep up the good work!