In the early days of the COVID pandemic, as the virus spread through Wuhan, and then other parts of the world, many countries took unprecedented steps to control the disease. Alexis Madrigal and Robinson Meyer, both journalists at The Atlantic, expected to see the same kind of massive mobilization of federal resources when the virus arrived in the U.S.

“I expected that we had the world’s foremost infectious disease fighting agency in the world,” says Madrigal. “And so I was expecting to see the United States of America assume global leadership and come up with ways for us to deal with it.”

While the U.S. did experience weeks of lockdowns, we didn’t see the same level of mass testing that was happening in parts of Asia. In fact, when Madrigal and Meyer started looking, it was hard to find any concrete numbers at all about how much testing was happening in this country.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) had stopped reporting national numbers in early March 2020, and so the reporters ultimately reached out to all fifty states to ask some basic questions about their testing capacity. They discovered the country was botching its testing effort. Fewer than 2,000 people had been tested for the virus at that point, despite the government’s assurances that tens and even hundreds of thousands of people could be tested per day.

Testing was our most crucial data point for understanding the early dynamics of the pandemic. But it wasn’t the only data that was falling short. It was also difficult to find numbers on how many people were hospitalized and how many people had died. And so, after publishing their testing story, Meyer and Madrigal teamed up with Jeff Hammerbacher, a scientist and software developer, to compile their own nationwide data sets, based on what states were publishing. They figured it was a stopgap. They planned to gather numbers until the federal government began releasing more of its own.

The Importance of Data

Data is the lifeblood of public health, and has been since the beginning of the field. One of the first sources of public health data was the Bills of Mortality, a series of mortality reports published in London in the 1600s. Every week a group of parish clerks would gather and share information about who had died in the neighborhood that week, and how.

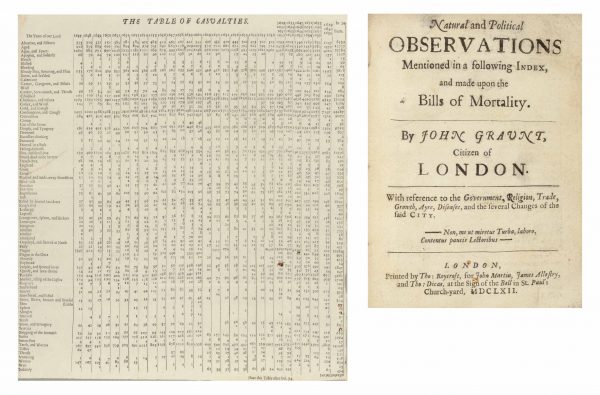

According to Steven Johnson, author of Extra Life: A Short History of Living Longer, the Bills were a source of fascination and gossip, but they weren’t “structured data” — meaning there wasn’t a way to detect useful patterns in the information. But then John Graunt, a haberdasher and amateur demographer, decided there was more to be learned from the documents. “It occurred to him at some point in the early 1660s,” Johnson explains,” that if you tried to assemble that data and look at it systematically that you might be able to tell a lot more about what was really happening to the health of Londoners.”

According to Steven Johnson, author of Extra Life: A Short History of Living Longer, the Bills were a source of fascination and gossip, but they weren’t “structured data” — meaning there wasn’t a way to detect useful patterns in the information. But then John Graunt, a haberdasher and amateur demographer, decided there was more to be learned from the documents. “It occurred to him at some point in the early 1660s,” Johnson explains,” that if you tried to assemble that data and look at it systematically that you might be able to tell a lot more about what was really happening to the health of Londoners.”

Graunt gathered information across parishes, tabulated it, and organized it in a more structured way. He ultimately published a report called “Natural Observations Mentioned in a Following Index and Made Upon the Bills of Mortality.” That verbosely titled document would go on to become the founding text of medical statistics and public health data, allowing Graunt — and health officials — to answer the question, “what is really killing people?”

Graunt’s work represented a huge conceptual breakthrough, but ultimately it wasn’t that useful. That’s partly because there was still a limited understanding about what was actually killing people. The “causes of death” tabulated in his report included, “apoplex,” “cut of the stone,” “falling sickness,” “dead in the streets,” and “suddenly,” among others. Beyond those limitations, there weren’t yet institutions that could coordinate a public health response.

The Fractured System

In the 1800s, a number of cholera epidemics swept across the United States. In response, cities and states across the country started to establish local public health departments. But the system in the U.S. grew in a mostly bottom-up way. Cities and states led the way while it took decades before any real national public health institutions came into being.

There was one national agency, established in 1798, called the Marine Hospital Service, which cared for sick and injured sailors. Eventually, in 1912, that agency became the U.S. Public Health Service.

“It started taking on greater powers, but it was still very hesitant to interfere in anything that was local,” says David Rosner, a historian of public health at Columbia University.

Over the next few decades, the national system grew. The CDC eventually emerged from the Public Health Service and became, in many ways, the best disease-fighting agency in the world. They pioneered the data-driven response, employing statistics to figure out who was being hit by disease and how to intervene.

The CDC had some huge successes. The agency helped with the polio effort, eradicated smallpox, started the fight against HIV, and stopped Ebola more than once. Over time it developed a heroic reputation.

The CDC had some huge successes. The agency helped with the polio effort, eradicated smallpox, started the fight against HIV, and stopped Ebola more than once. Over time it developed a heroic reputation.

But there was always an underlying weakness in the U.S. system, which was its fractured nature. It wasn’t a coordinated system like some countries have. Instead, the U.S. system is a patchwork of thousands of state and local health departments that all operate fairly independently. The CDC can issue guidance, but ultimately state and local health departments answer more to their local elected officials than they do to the CDC.

Making matters worse, the public health system struggled with consistent funding. When there was an immediate crisis, there would be an infusion of cash. But then, when the crisis passed, the resources would evaporate. And this problem only accelerated from the Reagan era onwards. Public health agencies saw their budgets get cut decade after decade, all the way into the 2000s. The CDC’s budget dropped overall from 2010 to 2019. Over the same time period, local public health departments lost more than 50,000 jobs due to funding cuts. Lots of privatization happened during this time as well, as contractors were hired to do what the government used to do.

Investigating the System

This was the system that Alexis Madrigal and Robinson Meyer encountered when they set out to gather their own COVID related data at the start of the pandemic. It was a system defined by its many labyrinthine reporting entities and jurisdictions. Says Madrigal:

“We have built these data systems over time in this kind of sedimentary pile. And it’s very difficult to change them when it’s not a crisis.”

Madrigal began recruiting volunteers to help with the data-gathering effort and, within weeks, had several hundred people helping out, ranging from students and tech workers to doctors and journalists. The group became known as The COVID Tracking Project.

Every day, the group would reach out to every state and territory in the U.S. to find out how many tests they’d done, and numbers of positive cases, hospitalizations, and deaths. They’d enter all their information into a spreadsheet and commit the numbers. Madrigal says it seemed simple enough at first. But over time, as they began to understand the idiosyncrasies of the system — and the data itself — it became much harder.

Even something as simple as a “case of COVID” was not easy to define or count. Erin Kissane, the managing editor of the project, says that in some states a case is a “confirmed case.” In other states, it’s a “confirmed” or “probable case.” And this kind of ambiguity was true for most of the metrics the project was tracking.

“There were all of these different ways that what the states were sending the federal government was just slightly different,” says Madrigal. “You had different data definitions, you had different systems. And no one really had any idea of how to standardize those things, particularly in the midst of a crisis like this.”

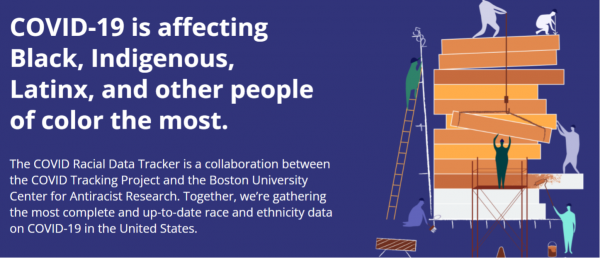

Ultimately, the COVID Tracking Project would decipher and document many examples of how our COVID data is unstandardized or incomplete. They chronicled the way that local health departments’ reliance on fax machines often resulted in distortions in data. They teased out the way that death numbers would lag when big surges happened, often because the people who fill out death certificates would get behind. They helped compile what was then the country’s most complete and up-to-date dataset on race and ethnicity data for COVID-19. And they dedicated themselves to analyzing and explaining the data in a way the public could understand, going so far as to run a public health desk.

Becoming the System

In the early days of the pandemic, the founders of the COVID Tracking Project thought the government had its own comprehensive numbers that it just wasn’t releasing or publicizing. But then the CTP founders started noticing some strange coincidences. When Vice President Mike Pence presented data at his Coronavirus Task Force press briefings, the numbers often tracked very closely with what the CTP had gathered.

“I think a few of us started to suspect at that point that he was actually reading our numbers just rounded,” Kissane says.

Their suspicion that the government was using CTP numbers was later confirmed, when the Trump administration published a report that used the project’s data and charts.

For its part, the CDC came into the pandemic with data systems that were not designed to gather and process the kind of fast, high-resolution data that people wanted. The demand for data went way beyond what the public health system had encountered before.

There were a number of ways the CDC tried to compensate. In April 2020, the agency began working with the Association of Public Health Laboratories to create the COVID-19 Electronic Laboratory Reporting Program (CELR), which would eventually collected COVID-19 testing data from every state. It took a little more than a year for the federal government to onboard all the states to that system.

In the meantime, the CDC adapted some of its surveillance systems and methods to track the new disease. This included their flu reporting systems and their syndromic surveillance systems.

But the agency’s existing systems just weren’t working that well. The agency was struggling to keep track of testing and case rates across the country. It was moving so slowly with its hospital data that eventually the agency that oversees them, HHS, took over gathering those stats.

The agency also eventually released its own data tracker but there continued to be problems with the data and large discrepancies between their testing numbers and state numbers.

Ending the COVID Tracking Project

About a year into the pandemic, as the Biden administration was coming into office and as vaccinations were rolling out, the founders of the COVID Tracking Project made the decision to end their work. They’d never intended the CTP to be a long-term project.

As federal data continued to improve, they also wanted members of the public, journalists, and policymakers to turn back to the government for that information. “We did not think that the public health data in widest distribution for the United States in the COVID pandemic should come from volunteer labor,” says Kissane.

But some of the Biden administration’s promises have not yet materialized. The “pandemic dashboard” that COVID Tracking Project members advised on has not yet been built. And communication around data — its meanings and its limitations — remains lacking. “Data can’t talk. Data can’t explain itself,” says Kissane.

“The data has to be contextualized and explained and that’s still largely not happening.

Fixing the System

While there were some improvements made to our public health surveillance systems during the pandemic, we are still nowhere near having the systems we will need the next time a pandemic happens.

Dr. Thomas Frieden, former director of the CDC, has called for a multi-year investment to overhaul our informatics systems. “You can’t fix the data system without fixing the broader public health system,” he explains. He cites overwhelmed local and state health departments, hospitals without standardized data systems, insufficient laboratory testing, and a poor contact tracing system as contributing factors to the problems with the system. Fixing the system, he says, will require fixing the way we fund public health. We need to dedicate significant money, available for years, to rebuild this critical infrastructure.

Dr. Thomas Frieden, former director of the CDC, has called for a multi-year investment to overhaul our informatics systems. “You can’t fix the data system without fixing the broader public health system,” he explains. He cites overwhelmed local and state health departments, hospitals without standardized data systems, insufficient laboratory testing, and a poor contact tracing system as contributing factors to the problems with the system. Fixing the system, he says, will require fixing the way we fund public health. We need to dedicate significant money, available for years, to rebuild this critical infrastructure.

As we rebuild our systems, it’s worth rethinking how we collect race and ethnicity data in particular, which represents one of the biggest gaps in our current knowledge. Abigail Echo-Hawk is a citizen of the Pawnee Nation of Oklahoma and director of the Urban Indian Health Institute, and ever since she started her career in public health, she has seen the ways that Native people – and other people of color – are made invisible in the data. One way it happens is by virtue of being a small population that can be difficult to gather “statistically significant” data about. Another way is through “racial misclassification,” when whoever is gathering the information doesn’t ask a person what their racial background is and instead makes an assumption.

People may also get categorized as “Other” or “Multiple Races.” If that data isn’t disaggregated, it effectively hides what’s happening to a particular population of people. Broad categories like “Asian American” also hide the fact that Asian Americans are an incredibly diverse group, with very different experiences related to health and illness.

Echo-Hawk advocates for “decolonizing data” and creating a framework in which data better serves community needs. She recently served on a commission that made recommendations for an equity-centered data system.

Leave a Comment

Share