The announcement by Ford that the iconic, long-abandoned Michigan Central Station in Detroit would be revived brought a wave of press coverage, but something else as well: a series of offers to return artifacts taken from the structure during its decades of disuse.

It all started with an anonymous caller who reached out to the Henry Ford Museum looking to return a large antique clock that had once hung in the train station. The presumed thief texted the clock’s location (outside an abandoned warehouse) and suggested that a truck and retrieval team be dispatched to carefully reclaim the artifact. Ford picked up the wrapped clock and verified its authenticity — and that successful pickup appears to be just the beginning.

With the clock in hand, Ford put out a public call with a no-questions-asked policy toward further returns of historical artifacts. Since then, dozens of people have called in to offer additional objects including fountains, plaster medallions and light fixtures. Ford is also hoping that key items like ticket window grills, elevator transom panels, additional clocks and other decorative ornamentation will show back up as well.

Microcosm of Motor City

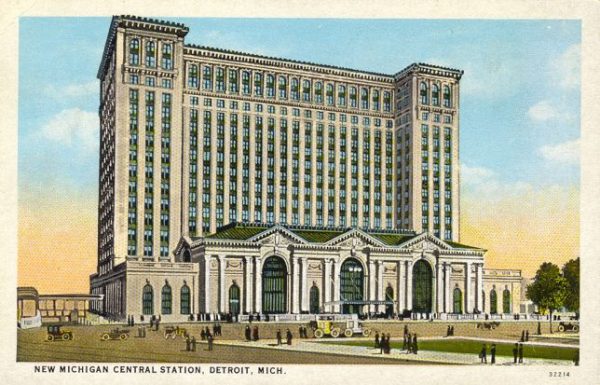

Michigan Central Station was to be the Grand Central Terminal of the Midwest (designed, in fact, by the same architects). The main waiting area was modeled after an ancient Roman bathhouse, with marble walls and vaulted ceilings. Brick walls of the concourse were illuminated by a large copper skylight. The bold new station would handle freight and mail as well as passengers.

Completed in 1913, the Beaux-Arts building slowly transitioned from a transit icon to a visible indicator of the city’s economic decline. Fueled in part by the regional automotive industry, the rise of the car and associated white flight arguably helped drive it out of business, making this transportation structure a particularly fraught symbol. Visible off the highway on a major route into town, it is also hard to miss.

The station changed hands a number of times over the years. At points along the way, it was considered for rehabilitation as part of various local development schemes. There were plans to turn it into a police station or a convention center and casino, among other things. At times, the building also faced existential threats of demolition, too, staved off in part by its designation as a historic landmark.

The 18-story structure incrementally closed down over the years — its upper offices were slowly vacated, shops and restaurant shuttered, and then, finally, the ticketing windows closed, too. Deserted entirely in the late 1980s, the building began to fall into disrepair.

This abandonment was a big draw to urban explorers who would break in and photograph the famous building. And for some, taking pictures wasn’t enough — over time, hundreds of artifacts were removed from the building’s facade and interior, including the now-returned clock.

Recently, however, the previous owners started to take stock of the building’s potential, and incrementally renovate it for potential reoccupation. They drained the flooded basement, removed broken glass, added new windows and reinforced perimeter security.

Fording Ahead

Earlier this year, the Ford Motor Company purchased the property, subsequently announcing that it would become a Corktown campus hub, part of a larger autonomous vehicle development center. Design partners from Snøhetta, an acclaimed international architecture firm, are working with Ford on the architectural remodel and campus plan.

“As Ford envisions the future of mobility,” they write, “Ford and Snøhetta will rethink existing cities in addition to creating new urban spaces and mobility systems through responsible and sustainable urban planning, product design, and business practices.”

This new complex won’t be just about cars, either. “New and innovative roadways, parking facilities, and integrated pedestrian connections are just some of the design considerations that will highlight the positive impact of Ford’s future mobility technologies.”

Inside, the first level of the station will reopen with restaurants and retail, recalling its original mixed-use functions. Condos as well as offices for Ford suppliers and partner companies will fill out the floors above, remaking the building into a new kind of transit hub.

The company, meanwhile, is still not sure how to process all of the artifacts and other offers of assistance. Some may be integrated into the rehab and others sent to museums. But regardless of where the items wind up, these acts reflect a vested interest of citizens in their city, and a central structure that has stood there for over a century.

Leave a Comment

Share