Between bouts of intense action, World War II soldiers spent a lot of time craving ways to occupy themselves and books were a welcome relief during the ongoing conflict. The U.S. Council on Books in Wartime (motto: “weapons in the war of ideas”) saw these as critical, too. They ended up distributing over 100,000,000 copies of more than a thousand slim editions to armed forces overseas. Treated by troops as rare treasures, these would get passed around until they were illegible. And their adoption transformed the publishing industry, elevating paperbacks from second-class printings to patriot volumes.

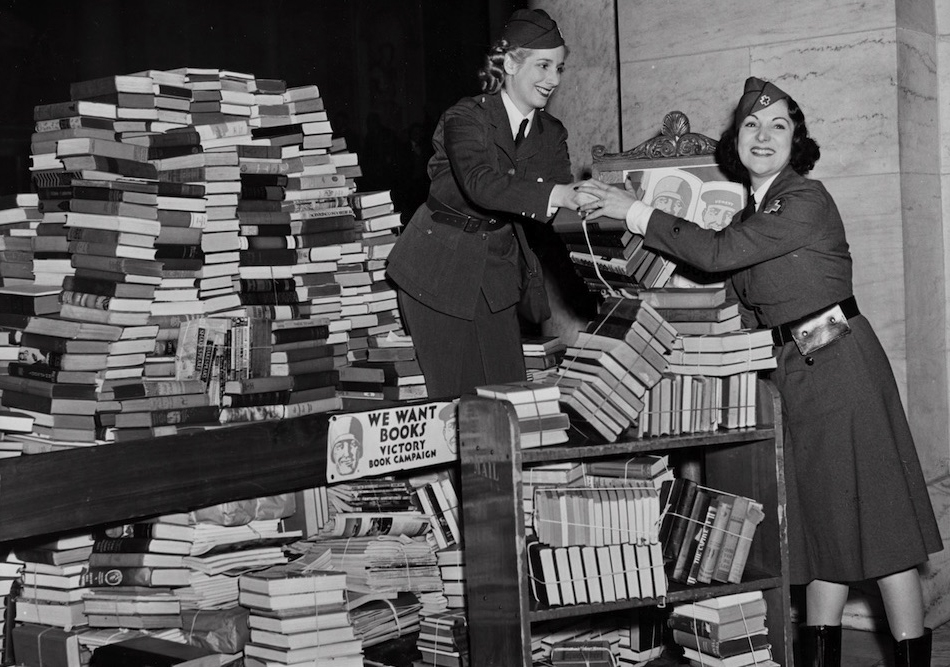

Early efforts to gather and ship books to American troops serving abroad had mixed results. Citizens donated all kinds of reading material during national book drives run by libraries, but much of this was deemed a poor content fit for soldiers. On the format front, larger hardcovers were heavy and took up too much space. Also, the string and glue found in traditionally bound books proved to be insufficiently durable, unable to stand up to decay and insects in front-line trenches.

So the U.S. Army’s Library Section chief, a man by the name of Raymond Trautman, set out to do something fundamentally different, providing an array of content options in a more robust and portable format. He talked to authors and designers about how to best get books to troops, and came up with Armed Services Editions (or: ASEs).

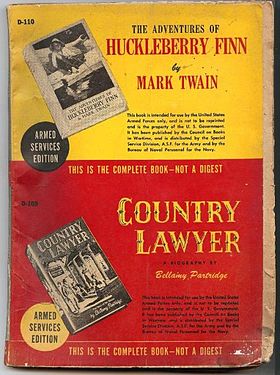

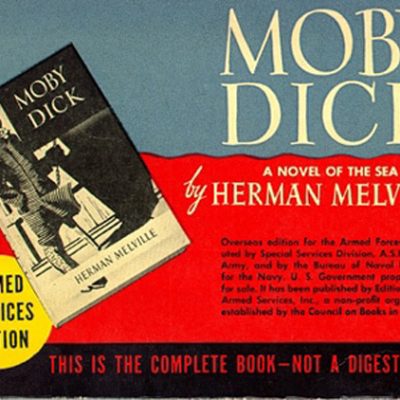

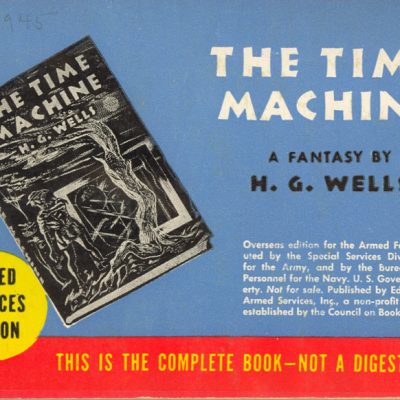

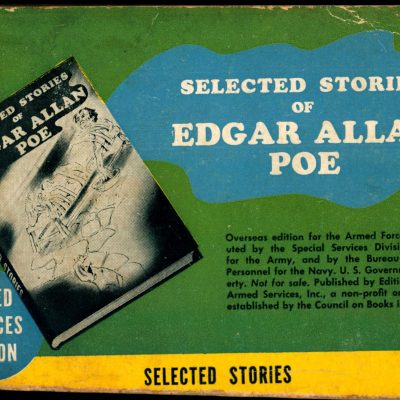

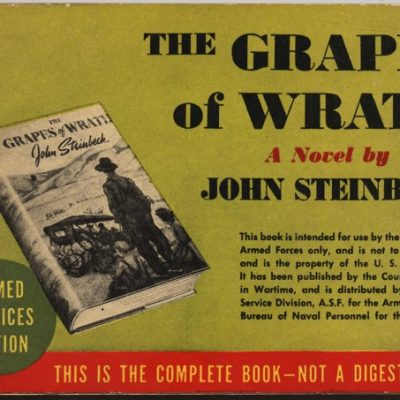

In terms of content, The ASE program offered an assortment of both fiction and nonfiction titles, including: classics, best-sellers, biographies, drama, poetry and genre fiction (mysteries, sports, fantasy, adventure and more); nonfiction books included self-help and biographies.

But there was still the issue of design and construction — these books had to be easy to make, ship and carry once deployed. And that meant they had to be thin and small, like a paperback, but flatter, more like a magazine. So instead of using book presses, the Army turned to pulp magazine makers and began printing slim volumes “two high” then slicing them down the center. In many cases, these were then “bound” simply with a staple.

But there was still the issue of design and construction — these books had to be easy to make, ship and carry once deployed. And that meant they had to be thin and small, like a paperback, but flatter, more like a magazine. So instead of using book presses, the Army turned to pulp magazine makers and began printing slim volumes “two high” then slicing them down the center. In many cases, these were then “bound” simply with a staple.

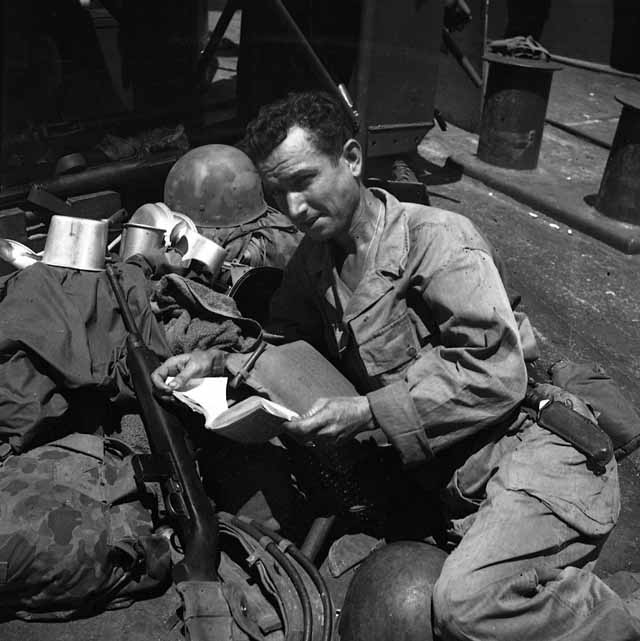

At six cents per copy, the resulting books were inexpensive to produce and would often make use of inactive presses between other printings. They were beloved by soldiers, who could quickly and easily tuck them into pockets or helmets when on the move. Because the little volumes looked so much like flip books or pamphlets, messages were attached to explain to new readers: “this is a complete book – not a digest.” These new, specially made volumes began shipping out in 1943.

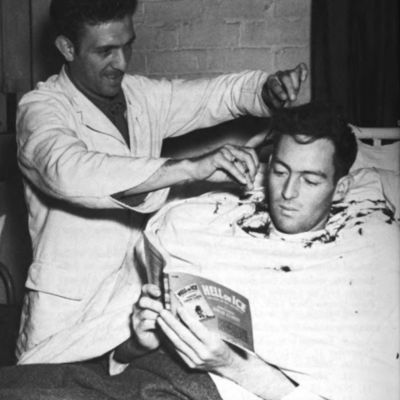

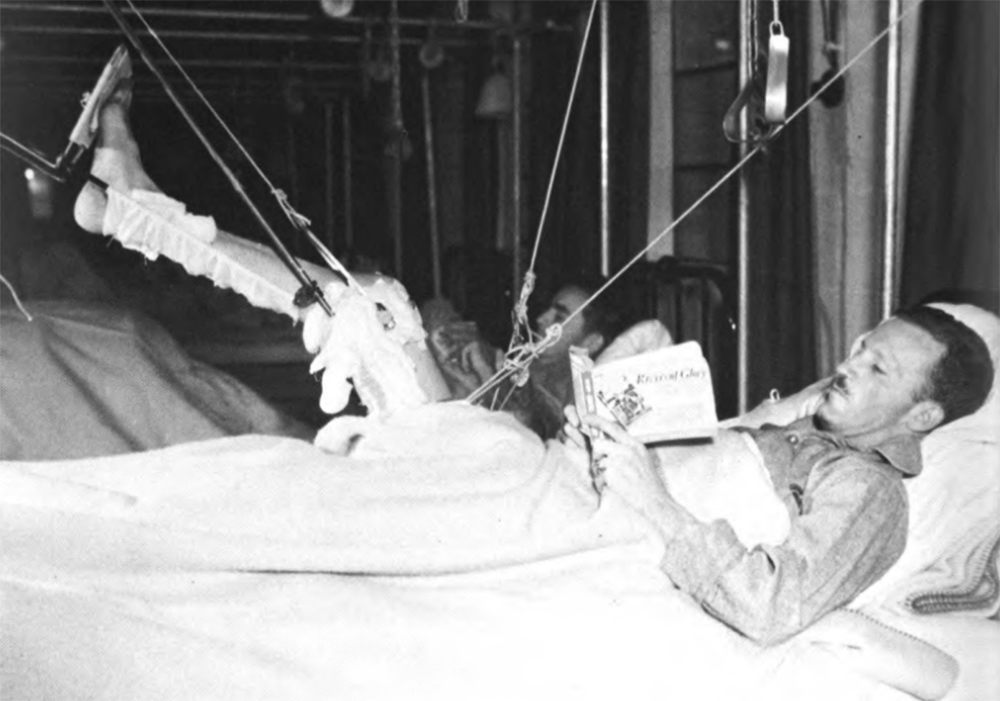

The books were sent out in boxes to Europe and dropped in crates from the sky over Pacific outposts, eagerly grabbed up by soldiers around the world. They were read on the front lines, during mealtimes and in hospital recovery wards. Many authors whose work was selected for the ASE program found themselves inundated with fan mail.

There was something bigger in play, too: books took on a special meaning in the context of an enemy who would ban and burn them. The” war of ideas” wasn’t just about what was within the books, but also what they symbolized in a larger fight for freedom.

By the time the war ended and troops came home, paperbacks had developed a fresh set of associations. They went from being the stuff of pulp fiction to the reading material of victorious soldiers, made to be read and passed, not handled delicately and stored on shelves. Within a few years, softcovers were outselling hardcovers across the U.S.

Comments (1)

Share

I work in a used bookstore, and we used to have a crate or so of these. I believe they eventually did sell, but it was awkward to have them on the shelves, because they didn’t match the form-factor if anything modern.