Coins, bones, toys and weapons are among the hundreds of thousands of artifacts recently surfaced from the canals of Amsterdam. Meticulously catalogued by location and organized by age, these finds span the Dutch capital’s 800-year history. Their rediscovery and display was made possible by a massive excavation project being undertaken to create a new metro line through the city, carefully orchestrated to operate alongside an unprecedented archeological dig.

The associated website, book and documentary set titled Below the Surface has been years in the making. This project catalogues everything from bits of ceramic, metal and glass to fully intact artifacts. Some finds predate the city’s founding — there are medieval coins and even pieces of sharpened stone from as far back as 4,300 BCE.

“Rivers in cities are unlikely archaeological sites,” explain the organizers and curators of the project. “It is not often that a riverbed, let alone one in the middle of a city, is pumped dry and can be systematically examined. The excavations in the Amstel yielded a deluge of finds.” The resulting website is an amazing interactive museum, allowing visitors to dynamically connect various artifacts by type, material and time period.

Carefully Dredging Up History

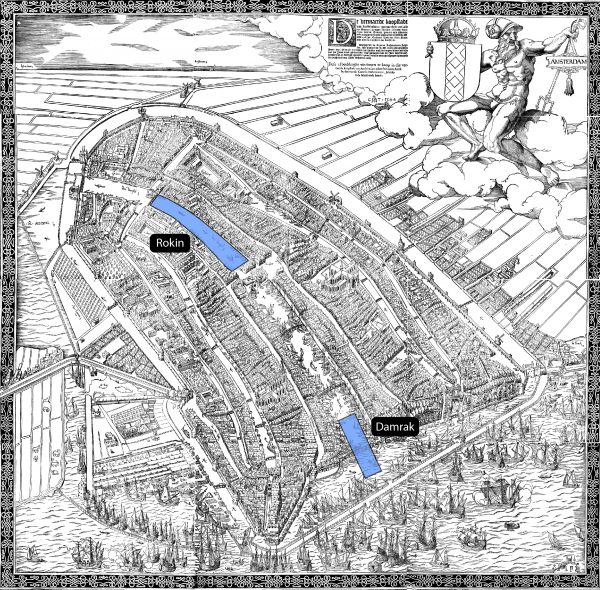

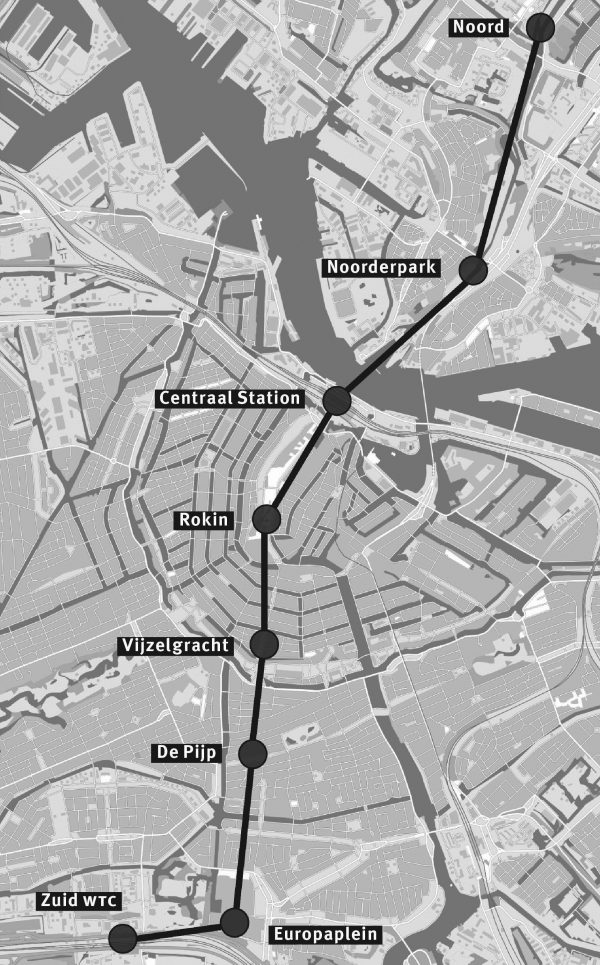

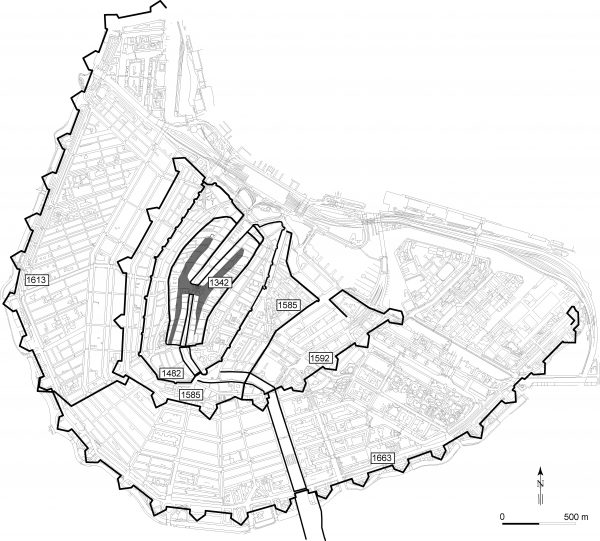

Plans for a new north/south metro line in Amsterdam date back over half a century, but the city didn’t break ground on the route until the early 2000s. This long delay came in part because other 20th-century transit construction had historically resulted in canal-side building demolitions, creating a public backlash against further development.

This time, city officials resolved to minimize disruption to historic surroundings, opting to bore a tunnel instead. But their consideration for history also extended below the surface. Amsterdam’s Office of Monuments & Archaeology (M&A) got involved, assessing different options for excavating and documenting finds along the way.

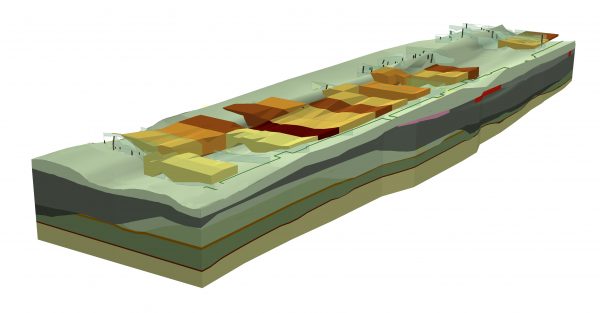

While tunnel sections were bored horizontally, displacing soil, water and artifacts in a less-controlled fashion, vertically dug station sites presented an opportunity for controlled discovery. Ground at these sites was carved out from above, allowing layers of artifacts to be gathered and sorted along the way. This was vital in keeping track of where things came from in the process. “Spatial or landscape context is paramount for archaeological interpretation. Finds have added value if they are mutually related and connected with their surroundings … otherwise, out of context, their only significance is their intrinsic value.”

Geological layers provided helpful context, too. “Based on sediments, shells, diatoms, pollens, seeds and other such organic and geological remains (ecofacts), data was collected on the development and age of the river and the role it played in the wider landscape.” This dimension was also “not confined to the period of Amsterdam’s history but spans the long (prehistoric) period that predated this, for as a landscape element the River Amstel is much older than the city.” Between the natural finds and human artifacts, this project traces the history of an ancient place from well before its time as a trading post.

So why are waterways of particular interest? “The answer is simple: in rivers, canals and open water material remains can sink to the bottom and large quantities can pile up over time.” Some of these finds may have fallen from passing boats, but other “archaeological remains can also be connected with activities ashore. As such, they can often be linked to objects associated with a building or structure, workshop or installation along the bank.” What sinks down, from ships or shore, winds up creating layers that can be tied to different periods of local history, along a more expansive route rather than a single dig site.

Digging Through the Artifacts

Perhaps most impressive result of all this work, though, is the digital archaeological database, representing “an interpretive instrument that can be organized in different ways based on the data categories.” The various “finds can be sorted into groups by establishing links between their respective attributes. All sorts of comparisons can be made, based, for example, on dating, type of material, use, special origins, or combinations of these.” Within groups, “further connections can be established, thereby refining the find categories in response to specific research questions.” For example, researchers can group “all the knives with brass fittings from Damrak dated between 1500 and 1600.”

Dimensions and production methods can be used to sort through the artifacts, as well as functional categories, like: buildings & structures, interiors & accessories, distribution & transport, craft & industry, science & technology, arms & armor, communications & exchange and more. It really is worth surfing through the collection online.

In the end, “the enormous quantity, great variety and everyday nature of these material remains make them rare sources of urban history. The picture they paint of their era is extremely detailed and yet entirely random due to the chance of objects remaining or sinking down into the riverbed and being retrieved from there. This is what makes this collection so fascinating, so poetically breathtaking and abstract at one and the same time.” This database is a work of both of archeology but also a kind of found art archive, allowing users to create their own connections. The extensive unearthing process is well-documented on Below the Surface (as are the implications of various historic finds).

Leave a Comment

Share