In the town of Colma, California, the dead outnumber the living by a thousand to one. Located just ten miles south of San Francisco, it is filled with rolling green hills, manicured hedges, and 17 full size cemeteries (18 if you include the pet cemetery). 73% of Colma is taken up by graveyards. Their motto? “It’s great to be alive in Colma.”

Maureen O’Connor, President of the Colma Historical Association, says it is the only true necropolis in the United States — a place primarily dedicated to the dead.

From a distance, Colma looks a bit like a sprawling city , its landscapes dotted with mausoleums, monuments, towers and tombstones. It is home to just 1,600 living citizens but also houses the remains of a million and a half humans.

Numerous famous people are interred in Colma, including John Daly (for whom Daly City is named), Joe DiMaggio and Levi Strauss. Tina Turner’s dog is buried in the Pet Cemetery.

A Growing Necropolis

Colma was not always a necropolis. Over its history, the land was used for vegetable, flower, and hog farming. But as San Francisco’s cemeteries started to fill up in the late 1800s, Churches and other organizations began buying plots for burials south of the city. Finally, in 1924, the area cemeteries incorporated and became the town of Lawndale. It was renamed Colma in 1941.

All of this was happening in the context of a much bigger change in American burial practices. For a long time, the dead were buried in little squares or churchyards. Burial grounds doubled as public spaces in crowded cities: they were forums to hang out in and farmers grazed cows in them.

But by the 1820s and 30s, outbreaks of disease compelled city residents to keep the deceased far away from the living. And ever-rising real estate prices led property owners to prioritize breathing, paying tenants over dead ones. Gradually, the lands of the living and the lands of the dead began to diverge in America, and graves increasingly ended up located away from cities.

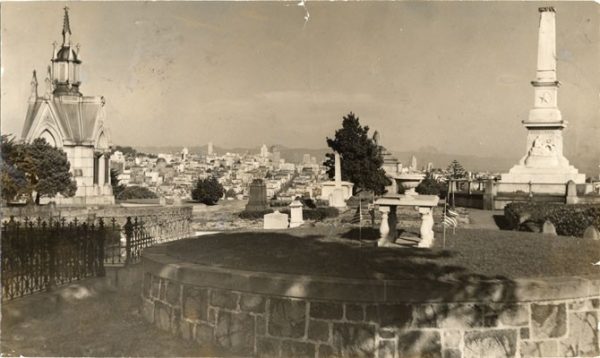

Mount Auburn Cemetery, outside of Cambridge, Massachusetts, was the first to be specifically called a “cemetery,” taken from a Greek word for sleeping chamber. Its carefully landscaped design, modeled on English garden traditions, signified a pivot in how people viewed and interacted with places for the dead. Cemeteries used to be humble plots right in the middle of the city, but Mount Auburn was designed to look like a garden paradise- lightyears apart from everyday life.

Mount Auburn was significant at time when many cities lacked public parks and would go on to influence the design of public spaces more broadly. Central Park in New York, college campuses and suburban subdivisions began to draw design inspiration from picturesque cemeteries, which were becoming spaces to walk, picnic, and escape from dirty cities. Colma also grew out of this precedent, and was designed in the Mount Auburn style.

“If the city of the living was designed for speed and efficiency and business,” suggests Keith Eggener, professor of architectural history at the University of Oregon and author of Cemeteries, “the city of the dead was instead understood as a kind of quiet peaceful Arcadia — an evocation of paradise or heaven on Earth.”

Crowding into Colma

In the wake of the Gold Rush, the population of San Francisco had boomed. And so had its death rate. Cemeteries were all over the city. And they were getting crowded.

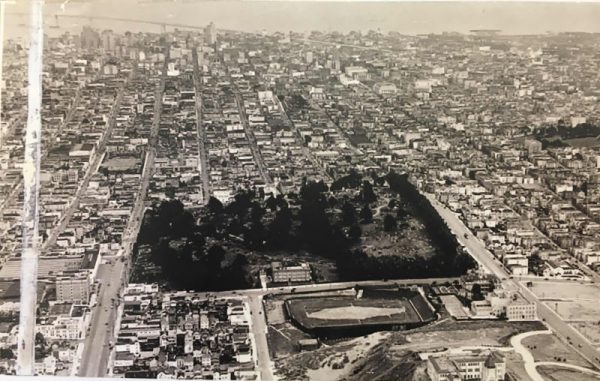

In 1900, the Board of Supervisors of the County of San Francisco decided to halt the expansion of cemeteries in the city — no new burials were allowed. This decision cut off funding for cemeteries, which fell into disrepair and became urban wastelands.

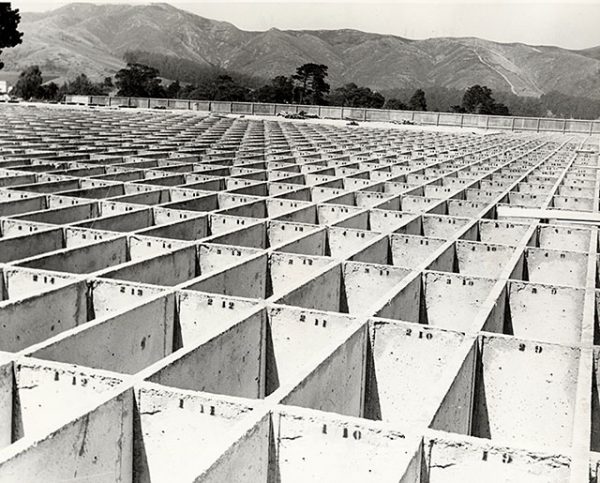

So in 1914, another ordinance was introduced to eliminate this blight by getting rid of cemeteries altogether. The bodies of some 150,000 people needed to be disinterred and moved to Colma.

To move a body with the headstone cost families ten dollars. If there was no money to be had, or no next of kin to be found, the body was put into a mass grave in Colma.

The individual headstones from these mass graves were reused as building material Some wound up at Ocean Beach where they were situated to help prevent coastal erosion. Others ended up in Buena Vista Park lining trails and gutters. These headstones (intact or in fragments) can be found all over the city.

Beyond Burial

Historically, Americans assumed they’d end up in their family plots or town churchyards alongside loved ones, but that is no longer the case. In these days of increased urban mobility, fewer and fewer people have a clear idea of where their final resting place will be.

Which is why many people opt not to be buried at all. Cremation has become increasingly popular, since ashes can be stored in one place, or scattered around the world. There are other options, too, like compressing cremains into diamonds for jewelry.

“So there’s a kind of break over the course of the last hundred years of more,” says Keith Eggener, “in which people were much more rooted to the land, both in life and especially in death, by virtue of burial (and knowing where they were going to be buried) than we are now.”

Even though Colma’s deceased residents had no idea they would wind up miles from their original grave sites in San Francisco, leaving only bits of their memorial markers behind in the beaches and parks of the city of the living .

Comments (8)

Share

Interesting. Not sure if you’re aware, but London used to have an entire railway system of the dead.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/London_Necropolis_Railway

Those interested in this subject should look up Bahrain. This small island in the Persian Gulf was once home to thousands of burial mounds. Quite a few are still visible today. They’re totally integrated in the urban fabric and are a normal sight for residents (including myself!).

There is an article in today’s (5/10/17) LA Times about the body of a 3 year old girl, died in 1873, who was reinterred to Colma from present day SF financial district http://www.latimes.com/local/lanow/la-me-ln-miranda-metal-casket-girl-identified-20170509-htmlstory.html

Very interesting stuff. There’s a fantastic documentary called A Second Final Rest (2004) that covers a lot of this material in some more depth. http://trinalopez.com/finalrest.html

And then there’s Colma: The Musical, of course! http://www.colmafilm.com/

On the same wavelength this month – I released a podcast, on Isn’t That Spatial, on the topic of cemeteries this month: https://isntthatspatial.net/2017/05/04/its009-cemeteries/

Americans are so egotistical. Do you really need to occupy a piece of land after you die?

It seems to me (I’m not an expert at all) that the fact we want our dead to be buried with headstones or have our ashes put somewhere meaningful stems from the idea we go somewhere when we die. The ancient Egyptians buried there dead with things to make them comfortable in the after life and it’s seems to me that kinda rolled over even in a world where the 3rd largest system of belief is atheism/agnosticism. Probably a study of it somewhere