Britt Young is a geographer and tech writer based in the bay area. She also has what’s called a “congenital upper limb deficiency.” In other words, she was born without the part of her arm just below her left elbow. She’s used different sorts of prosthetic devices her whole life, and in 2018, she celebrated the arrival of a brand new, multi-articulating prosthetic hand. This prosthetic hand has a sleek carbon fiber casing, with specific pre-programmed grips that she can control just by flexing the muscles in her residual limb. She can use a precision pinch to pick a hairpin off of the table, or a Hulk-style power fist to squeeze objects. This kind of assistive technology has been life-changing for a lot of people who have limb differences. But for Britt, in particular, it hasn’t been life-changing at all. In fact, her cutting-edge bionic arm has been a pretty major disappointment. “It’s just not what you imagine. It’s not like I’m like everyone else now, it’s something different.”

Artificial Limbs of War

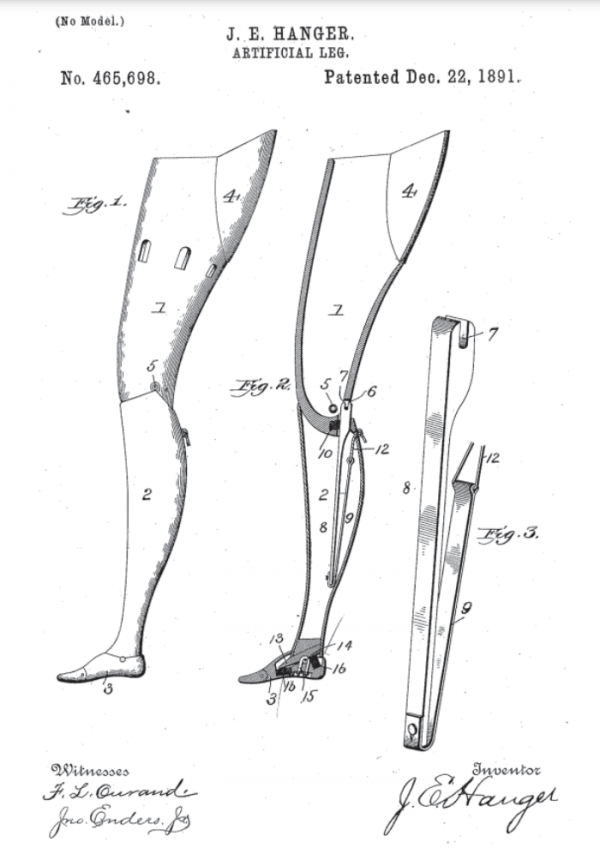

Prosthetics go back thousands of years. The earliest known prosthesis is actually a wooden toe that dates to ancient Egypt. But while we’ve had prosthetics forever, we’ve only seen major advancements in their design in the last couple hundred years, mostly because of the military. “Their development is intricately, intimately, inextricably tied to the military,” explains David Serlin, Associate Professor of Communication and Science Studies at UC San Diego. He says that the first major leap in prosthetics came after the Civil War which was considered the first modern war. The scale of damage inflicted on soldiers was completely unprecedented.

By the end of the war, tens of thousands of soldiers suffered amputations and needed help getting back to their lives. In response, the federal government began subsidizing artificial limbs for Union soldiers, while prosthetic companies sprang up to meet the spike in demand. In the process, available prosthetic technology for both veterans and civilians grew exponentially. Prostheses evolved from rudimentary wooden peg legs to artificial limbs with hinges at the ankles and knees to reproduce a natural gait.

Decades later, World War II led to even more prosthetic innovation. “Industrial science and engineering, science, material science, are all percolating in the 1930s and 40s.” In countries like the United States, Great Britain, and the Soviet Union, prosthetic sciences began to grow into industries. In the United States, in particular, a team of military personnel, engineers, and prosthetists came together at the request of the Surgeon General of the Army to form the Committee on Prosthetics Research and Development. They wanted to figure out how to actually develop prosthetics into a proper field of medicine.

The biggest challenge was developing a good artificial hand. Prosthetic legs are simpler to design and users tend to have higher satisfaction rates with them, but creating a hand that incorporated robotics wasn’t possible until well into the Cold War. “In the 1960s and 70s there were all of these engineering sciences that developed between the military and [universities], so instead of just developing napalm, they’re also developing technologies that allow you to use batteries for what are called myoelectric arms,” explains Serlin.

Wanna See Me Crush a Can?

A myoelectric arm is a battery-powered prosthesis that can be controlled by movements on the residual limb. In the early 1990s, Britt actually became one of the youngest children in the country to get one. At the time, these myoelectric hands were state-of-art compared to anything else on the market, but all that Britt’s hand could really do was pinch open and shut. “Mostly it was like it was like a party trick in middle school,” explains Britt. She worked with these devices all the way through middle school.

But as Britt got a little older, she realized just how useless her myoelectric hand really was. “It couldn’t even grab a piece of paper,” says Britt, “It would just slide right through.” By the time she was in high school, Britt abandoned her myoelectric hand and opted for a passive prosthesis. A passive prosthesis, also called a cosmetic prosthesis, is a device that closely resembles a natural limb. It doesn’t get you any attention… In fact, it serves the opposite purpose: to help you blend in. “Something deeply ingrained in me over my lifetime that I needed to wear this or else people are going to treat me differently.”

…We Have the Technology

In 2006 DARPA launched the Revolutionizing Prosthetics Program in response to the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. They wanted to address the shortcomings of available prosthetics for veterans with amputations by building the ultimate powered hand that would be sleeker and multi-articulating, meaning the individual digits on the hand could move and form different grip patterns. These new devices also looked bionic and invoked a type of robotic aesthetic that was popular in sci-fi films and comic books for decades. “There seem to be kind of like a weird alignment in the early 2000s where what was potentially possible technologically started to line up more with this vision of what is going to be attainable,” recalls Britt, “and that is perfectly replaceable prosthetic limbs.”

In 2018, tempted by all of these new advances in technology, Britt decided to make the leap and get her first myoelectric prosthesis in over 15 years. “There was a lot of anticipation that was being built among my friends and me for what at the time seemed like the coolest, most life-changing, cutting edge prosthetic arm that I would receive in my life,” Britt remembers.

At first, Britt was floored by her new bionic arm. The multi-articulating grips seemed like a huge upgrade, and the futuristic bionic aesthetic of her hand made her look and feel so cool, and she was getting a ton of positive attention. “They just want[ed] to see tricks. They want[ed] to see how it moved. […] It felt like middle school again.” But a lot like when she was in middle school, Britt quickly realized this high-tech piece of machinery wasn’t all that it was hyped up to be. It was heavy. It was hot. It was incredibly uncomfortable. But Britt still practiced with it every day, putting it on and trying to get her body used to the discomfort.

The point of assistive technology like prosthetic devices is to assist, but there were a lot of things this multi-articulating hand couldn’t do. Simple things, like turning a doorknob, or even cutting the cake at her arm-themed party. It was also frustrating to cycle through the multiple grip options in order to get the prosthetic hand to do what she wanted. Over her lifetime Britt has gotten really good at accomplishing most tasks one-handed, and it felt like having to do things with the bionic hand was just slowing her down. In the end, Britt ended up deciding that this incredibly advanced bionic arm wasn’t worth it at all and hasn’t used it much since.

The Lows of High-Tech

Advanced prosthetics like multi-articulating hands are absurdly expensive. Britt was lucky enough to have really good insurance which paid for the bulk of the price, but a complex myoelectric arm can cost anywhere from $20,000-$100,000. And even if you have good insurance, it can be a battle to get insurance companies to pay for even the most basic types of prosthetics, let alone the experimental high-tech kinds. Often these types of advanced assistive technologies are painted as “the best of the best,” but in reality, most people who would need them will never have access to them.

Despite the high financial cost and all of the functionality issues, Britt says a lot of people with limb differences still choose these types of advanced prosthetics over low-tech options in order to meet other people’s expectations. “It seems like there’s a little bit of an overbearing expectation that if you’re missing a limb, then you need to have a cyborg arm,” says Britt. “You need to be bionic because that’s cool.” Futuristic prosthetic technologies are exciting and draw a specific type of positive attention. And for a lot of people with limb differences, this attention can seem better than the alternative.

The way that high-tech prosthetics are viewed by people who don’t have limb differences can be damaging, and a lot of that has to do with how we talk about them. When the media reports on advanced prosthetic technology, they leave out the real-world challenges that people with limb differences can face when adapting to new technologies and focus on telling a feel-good story about disability. “Oftentimes prosthetic technology is viewed as the “savior” or the “superhero” type of thing that’s going to give us […] superhuman capacities,” says Debi Latour, occupational therapist and a prosthetic hand user, “But it’s a process.”

If you watch a lot of local news then you’ve probably come across a very specific type of viral video about advanced prosthetics. They’re feel-good videos that feature a child with a limb difference being given a new bionic arm and talks about how their life has been changed after being gifted their new prosthetic. In 2012, a disability rights activist named Stella Young coined a phrase for exactly this type of video: inspiration porn. She specifically used the word “porn” because she sees it as the objectification of one group for the benefit of another.

You see this a lot in reaction videos of babies hearing for the first time after receiving a cochlear implant too. These stories give people an unrealistic expectation of what advanced prosthetic devices can actually do for users. And they show a very narrow version of what thriving looks like for people with a disability. “All those “inspiration” stories, all of those “pity” stories, all of those “technology rescue” stories… all of those are a way for us to just cognitively contain difference and we can’t imagine that difference actually might be a form of flourishing,” explains Sara Hendren, professor of fine arts and design at Olin College of Engineering and author of What Can a Body Do? She says that these types of narratives teach us that the solution to someone having a limb difference is to build them a better hand, or the solution to a disability, in general, is to “fix” a body.

It’s not hard for people interested in building assistive tech to get caught up in this narrative too. Britt feels like the temptation for designers is to try and create an amazing new technology that can erase a person’s disability. Perhaps the better challenge is to design a world that can accommodate people with different types of bodies and different sets of abilities. “In a way, we’ve kind of chosen the messier way, which is trying to make every person who is not “whole” whole again with these kinds of problematic technologies… when we could make kitchen counters or cars more accessible to begin with that are more adaptable,” says Britt.

One Size Fits Few

A lot of people with limb differences can do tasks better with no prosthesis at all because they’ve developed their own adaptations. And for many others, the lower-tech options are actually a lot more functional. There are things like split hook prostheses, which are super reliable because they have no electronic components and don’t attempt to resemble a hand at all. There are over 2 million people in the United States living with limb differences, and every single one of those experiences is different. Satisfaction with a prosthetic device can depend on which limb is affected, or how many limbs are affected… It can depend on how high or low an amputation might be, or whether or not you were born with it. There is no such thing as one size fits all solution assistive tech, and we need to listen to what people actually need in order to navigate the world.

These days Britt doesn’t use her high-tech bionic arm and doesn’t even wear a cosmetic prosthesis anymore, but a couple of times a week she uses an activity-specific device which is a type of prosthetic socket with swappable attachments for things like exercising. It doesn’t try to resemble a natural hand at all, She has a clamp attachment so she can do kettlebell swings, and another called a “mushroom” that she uses to do balanced pushups.

Britt isn’t anti-technology, actually… She’s surprisingly optimistic about it. “I do think that the technology will improve,” says Britt, “I do think that there will be better options.” But in the meantime… she’s not going to just wait around for the perfect arm to get invented. She’ll keep using her mushroom, and her kettlebell clamp, and sometimes no prosthesis at all. And she’ll continue using all the strategies she’s developed to navigate a world that wasn’t built for her.

This episode was adapted from Britt Young’s article for Input Mag which you can read here.

Leave a Comment

Share