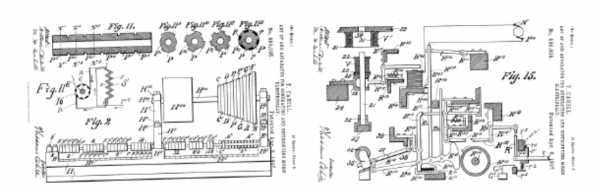

In the late 1800s, lawyer and inventor Thaddeus Cahill patented his “telharmonium,” a machine which would make music and pipe it across Manhattan along phone lines — a century before Rhapsody and Spotify arrived on the streaming scene. Initially, subscribers could dial in by phone to listen to live music synthesized on his vast contraption, but that was just the beginning of his grander vision.

Later, restaurants and hotels would likewise pay to stream these sounds into shared spaces. His tunes became a kind of proto-Muzak. But in this era before amps, end users had to attach paper funnels to boost volume.

Later, restaurants and hotels would likewise pay to stream these sounds into shared spaces. His tunes became a kind of proto-Muzak. But in this era before amps, end users had to attach paper funnels to boost volume.

At the heart of this music-making network was Telharmonic Hall, a building in the middle of New York City outfitted with around 200 tons of equipment and built out at an estimated cost of around $200,000. Cahill called this his “music plant,” and it aptly resembled something like a complex industrial factory filled with moving parts.

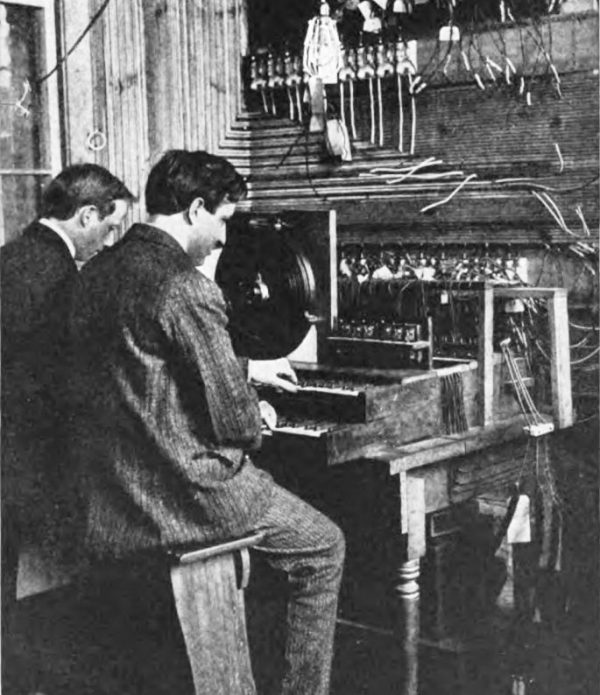

And behind the scenes, plugging away at a pair of piano-like keyboards, dedicated music makers input sounds into the system. Day or night, people could tune into whatever they were making — operas, symphonies, synthesized ragtime, even children’s lullabies. In an era with fewer home radios, the business was innovative, and showed real potential to change the listening habits of the city, if not the nation.

But there were drawbacks, not least of which was the issue of making the business financially successful. There was simply not enough adoption to offset the overhead costs. There was also the question of interference: phone calls were often interrupted by music bleeding in from the telharmonium. Broadcasts would sometimes even cut into official military radio channels. Scale, too, posed serious problems: more subscribers meant more power usage. In short: the further the telharmonium reached, the more infrastructure it required. After years of modest success, the machine was shut down for good.

Alas, no recordings of this technological marvel remain today. Still, the long-term impacts of this invention continue to reverberate. In his patent, Cahill called the act of creation “synthesizing,” and sure enough: his machine paved the way for future music synthesizers. And now, of course, we take on-demand media (including audio) for granted. All in all, Cahill’s telharmonium foreshadowed all kinds of later innovations, including synthesizers, streaming, and electronic music more broadly.

It would be hard to overstate the impact of this daring device. “Despite its final demise, the Telharmonium triggered the birth of electronic music …. The Italian Composer and intellectual Ferruccio Busoni was inspired by the machine at the height of its popularity and moved to write his ‘Sketch of a New Aesthetic of Music’ (1907) which in turn became the clarion call and inspiration for the new generation of electronic composers such as Edgard Varèse and Luigi Rusolo.”

Comments (2)

Share

I missed a little “shout out” to the Novachord only because Tiomkin found an effective use for it in the opening scene to HIGH NOON. I think an appropriate reference to this pioneer (Cahill) should be when a recorded voice

tells you to stay on the line for the next available representative, “Let me Cahill you for a moment” (music is then heard)”.

Cahill is an ugly expressway here in Sydney, and Aussies definitely wouldn’t get the reference to music.