In the months following the invasion of Ukraine, cryptic anti-war graffiti began popping up across Russia. People started writing out the phrase “no war” using asterisks instead of the various letters in order to disguise the meaning of the message. Then back in September, a woman in Russia wrote out the Russian word for “no” in chalk in the street. But then instead of writing out the Russian word for “war” – Войнa – she wrote just the first and last letters of the Russian word, with asterisks in between. Russian authorities had caught on to this trick with asterisks by this point, so the woman was detained by police and tried in court. In her defense, she claimed the missing letters were not actually from the word war, but rather a type fish that is spelled similarly. She was released by the judge, and now fish have become anti-war symbols!

This kind of cunning protest art makes for a good story. It shows how creative and resilient people can be in the face of political repression. But it can be hard to gauge its real-world impact. Painting a fish on the side of a wall probably isn’t going to bring down the regime. But there is an example from Soviet history of a time when art and humor made a massive difference in the trajectory of a different country: Poland. In the 1980s a Polish anti-communist group called the Orange Alternative also used a seemingly random symbol to spread its message: a mythical creature with a tiny pointed hat. And that innocent image amplified a powerful political message to the world, which ultimately contributed to the fall of the Soviet Union.

In the 1980s, Poland was one of many Eastern European countries aligned with the communist Soviet Union, which was in the throes of economic crisis. A labor movement took off named Solidarity. It was led by shipyard workers and it was the first independent labor union in a Soviet-bloc country. And millions of Polish people supported it. But the communist regime responded swiftly, placing the whole country under Martial Law in 1981. The media became heavily censored, curfews were put into place, and everyday movement was restricted.

Supporters of Solidarity started painting anti-communist messages all over Polish cities. But they would always get painted over by authorities, which left these paint spots everywhere.

A man named Waldemar “Major” Fydrych, grew fascinated with these paint spots. He was an undergraduate art history student at the time. Major was really into surrealism—which is all about using your irrational, unconscious mind and liberating yourselves from the boundaries of reality. One day he smoked a joint and fell asleep next to a children’s theater, and when he woke up, he saw a man in costume—a dwarf holding a bottle of beer. So he took that as a piece of surrealist inspiration, and decided to paint a stick figure dwarf with a little pointed hat in the middle of one of the white paint spots. Instead of the beer, he put a flower in it’s hand.

Around this time, Major helped found an a political art movement called the Orange Alternative. He and his fellow artists took a surrealist approach to protesting the government. They started paint hundreds of these dwarves in cities across Poland, as a way to point to the absurdity of everyday life under communism. And the silly images resonated with Polish people, in part because they broke through the monotony of martial law.

After about a year and a half of Martial Law, the Polish government had regained some control over the country. Thousands of Solidarity activists had been arrested, and many remained in jail. Meanwhile, outside of Poland, international pressure was mounting. Sanctions put in place by the United States were hurting the Polish economy. And in July of 1983, Martial law was officially lifted.

But the artists in the Orange Alternative remained anti-authoritarian advocates for free expression. They published a satirical political magazine and began staging ridiculous demonstrations that they called “happenings.” They took the dwarf graffiti, which by then had popped up all over Poland, and brought it to life in the real world.

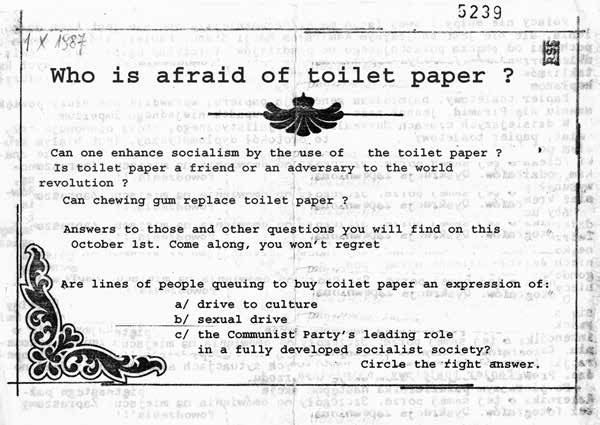

The Orange Alternative provided more than just comic relief, they also started handing out basic goods that were in short supply in Poland. At their happenings they would give out things like toilet paper and tampons. The police didn’t treat the Orange Alternative lightly. There were many arrests. But the cops also didn’t really know what to make of these artists in costumes handing out tampons.

By 1988, Poland was alive with revolution. The Solidarity labor movement was holding mass demonstrations. And the Orange Alternative’s happenings spread to cities across Poland, including Warsaw and Lodz. Thousands of people would gather to chant dwarves, dwarves, dwarves!

By the late 1980s, people all over central and Eastern Europe were taking to the streets and demanding freedom and democratic reforms. The Soviet Union was losing its grip on the people. In 1989, facing pressure from the public, Poland’s government agreed to hold parliamentary elections. When the votes were counted, leaders of the Solidarity labor movement won out over the communists. Communism fell in Poland, and it led to a domino effect that ended up taking down the entire Soviet Union. It’s hard to say exactly how important the artists of the Orange Alternative were to Poland peacefully winning its independence, but there’s a strong case to be made that they played a role, particularly in reducing bloodshed during tumultuous times.

Today, there’s a protest movement happening in Russia, which some people have compared to the Orange Alternative. It’s called The Little Picketers. The little picketers are small, clay figurines, about the size of the palm of your hand that are placed throughout Russian cities. Some of them hold peace signs, or Ukrainian flags, or anti-war messages. One of them is pictured holding a fish. It’s easy for anyone to get some clay and make a Little Picketer, and then discreetly drop it off in a public space without anyone else noticing. They usually get thrown away pretty quickly by Russian authorities — but before that happens, a photo is taken and submitted to an Instagram account, where they persist.

These Little Picketers are one of a number of ways that some people inside Russia are using play and humor to express their dissent, against a very serious, brutal war — a war that’s already killed tens of thousands of people. If nothing else, these small actions offer self-preservation, like a way to save your own soul. And you never know: sometimes a silly little symbol catches on.

Comments (1)

Share

Hey, nice to see story so close to home.

Just small correction all pictures from demonstration are from Wrocław, Street Protest on Świdnicka Street, not from Warsaw