That London Zoo’s Penguin Pool has serious issues is a fact that all relevant parties seems to agree on. The architect’s own daughter has gone so far as to suggest blowing up this iconic work. Still, who is to blame for its problems, what the fix should be, or whether it should even be saved at all have become the subjects of heated debate.

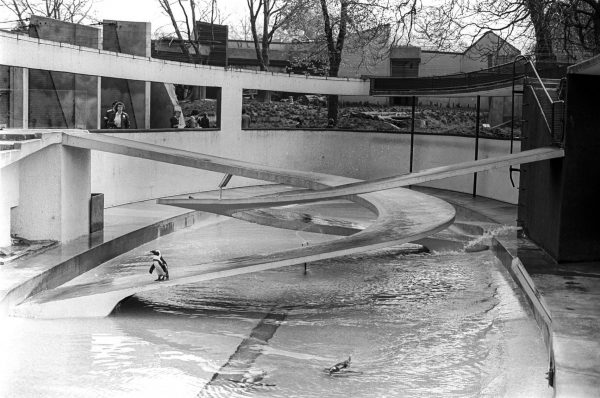

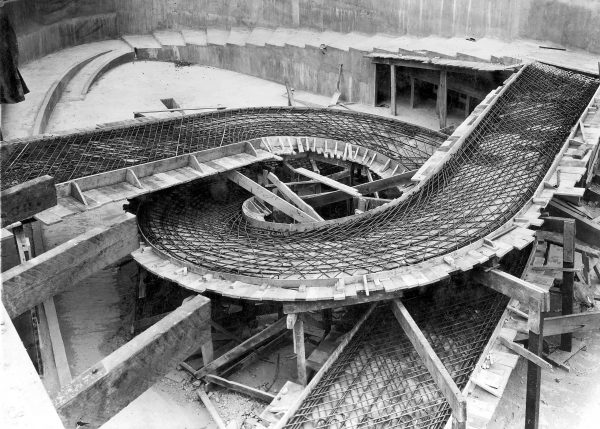

Built in 1934, Berthold Lubetkin’s penguin pool was a Modernist marvel. Its twisting pair of intertwined ramps highlighted how light and thin concrete could appear, unsupported over long spans and gracefully spiraling up into the air. Creating these interlocking surfaces was made possible with help from engineer Ove Arup, whose fame was later cemented through projects like the Sydney Opera House.

The London Zoo penguin pool has since been granted protected status as a landmark, for its place in Modernist history as well as the renown of its creators. And for a long time, it worked as designed, more or less: it housed penguins. But in the early 2000s, zookeepers determined that the concrete surfaces were promoting bumblefoot infections in these animal residents, who then had to be moved to a new penguin beach. The question ever since has been: what to do with this old pool?

Sasha, the architect’s daughter, lamented to the Camden Journal that the exhibit “was designed as a showcase and playground of captive penguins” and she “can’t see that it would be suited to anything else.” Plus, times have changed and our understanding of the needs of animals has as well, so in some ways the design, while eye-catching, is also outdated. Thus, she suggested: “Perhaps it’s time to blow it to smithereens.” Not everyone agrees with this assessment, however — in fact, some think it could work to this day, albeit with some caveats.

The pool has adamant defenders who contend that neither the designer nor the original structure are at fault for the current state of the structure or the injuries to its occupants. John Allan, who worked on restoring the penguin pool back in the 1980s, notes: “the original poolside paving was largely rubber, for the penguins’ comfort, but was replaced by the zoo with concrete.” Also, during the restoration, his team were asked to add quartz granules to help zookeepers gain traction on slippery surfaces. This demanded feature arguably created or at least exacerbated the infection of penguin feet within the exhibit.

Allan, who also wrote a biography of the pool’s architect, further points out that the original birds selected for the exhibit “were an Antarctic species which preferred to huddle together,” but that “these were replaced with South American Humbolts, which prefer to burrow, thus making the original nesting quarters less suitable.” His argument, in short, is that the zoo’s choices of materials and penguins is to blame. And he is not the only one to come to the structure’s defense.

George Osborne, editor of The Evening Standard, went so far as to claim that that destroying this landmark building would be an “an act of cultural vandalism,” calling Sasha Lubetkin’s comments “patricidal.” To its fans, the pool represents a turning point in architectural and engineering history, whatever its utility may (or may not) be today.

There is little question that this structure was ground-breaking. Per the V&A Museum: “The Penguin Pool provided Ove [Arup] the perfect opportunity to exploit the potential of reinforced concrete. He advanced the idea that the concrete slab or panel was the most effective form for reinforced concrete. He also proposed that concrete structures should be cast as one unit with the joints as strong as the central elements. He argued that with this approach any shape could be achieved.” Perhaps notably absent from this description of inventive engineering, though, is consideration of what actual penguins need.

For its part, the London Zoo seems more interested in the future than the past, boasting that its resident “penguins now live on Penguin Beach, Europe’s largest penguin pool, which has a rocky, sandy beach, nesting areas and a 1,200sqm pool holding 450,000 litres of water — alongside a penguin nursery where chicks can learn how to swim.” As for the old habitat: they have no plans for the place — it has become the proverbial elephant in the room, still there but not really addressed.

Special thanks to Stephen Wood and Daria Kwiatkowska for the story tip. Historical images via the RIBA Library Photographs Collection.

Comments (1)

Share

Hey Roman & crew at 99PI,

I grew up in England and remember spending many an afternoon watching the penguins in this cool enclosure during the 70’s & 80’s. Imagine my surprise when I saw Harry Styles dancing on the ramps in his new video ‘As It Was’.

https://youtu.be/H5v3kku4y6Q