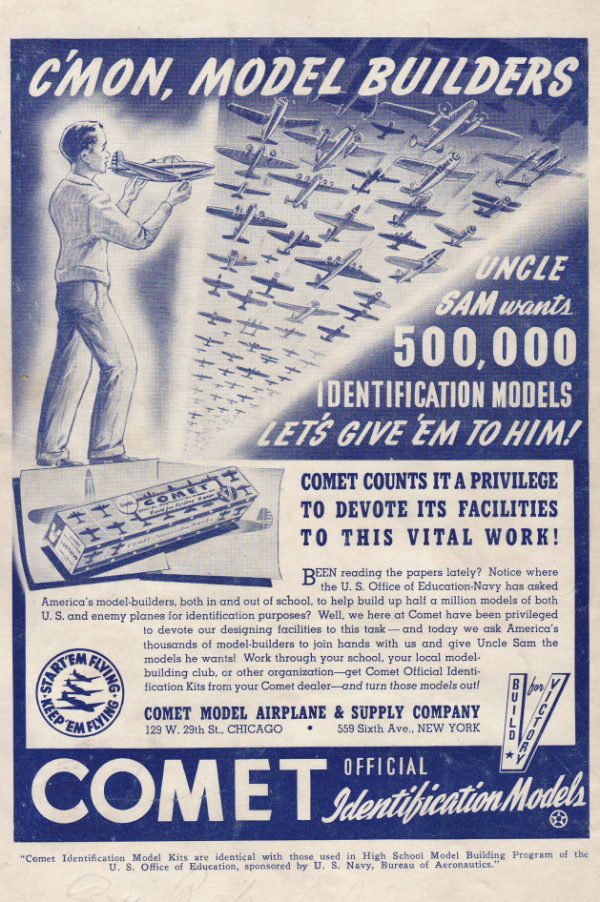

Following the 1941 aerial attack on Pearl Harbor, the U.S. Navy Bureau of Aeronautics put out a call to action, aimed not at recruiting adult volunteers or teen enlistees but schoolchildren. Across the country, kids were asked to create 500,000 scale aircraft models to help millions of civilians and soldiers tell friends from enemies during World War II.

“Your country needs scale model planes for the emergency,” read a public call for identification models. “They won’t be used in a display gallery or to show the handiwork of one’s leisure time. They will serve a definite purpose. They will be used for training military personnel in aircraft recognition and range estimation in gunnery practice. These models likewise will be important in the training of civilians in enemy plane detection, an essential element in civilian defense.”

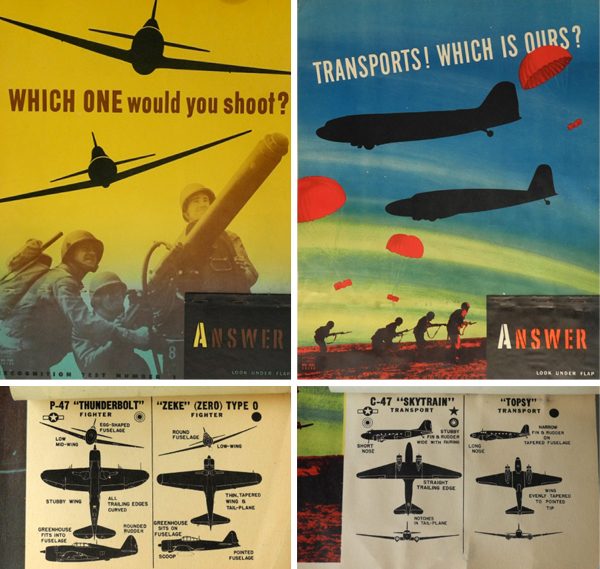

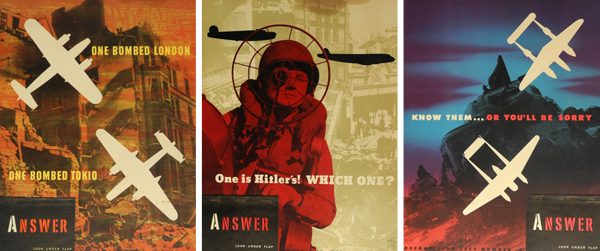

These “recognition models” (also known as “ID” or “spotter” models) were seen as critical to the war effort. Some were detailed for use in educational films or for marking identification, but many were simply painted black to simulate a silhouette. These helped familiarize observers with the outlines of planes from all possible angles.

Due to wartime shortages, most models were made of non-strategic materials. Some were built out of wood by schoolchildren — others by model-making companies, volunteers and cadets from paper, cardboard, plaster or injection-molded plastic.

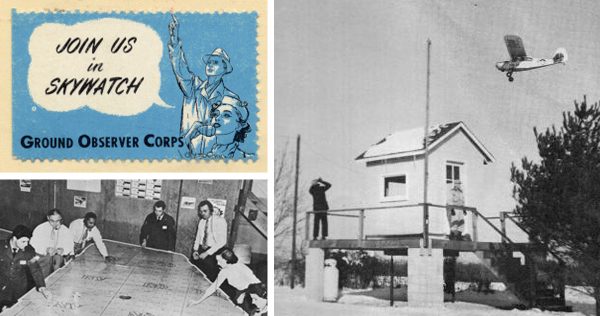

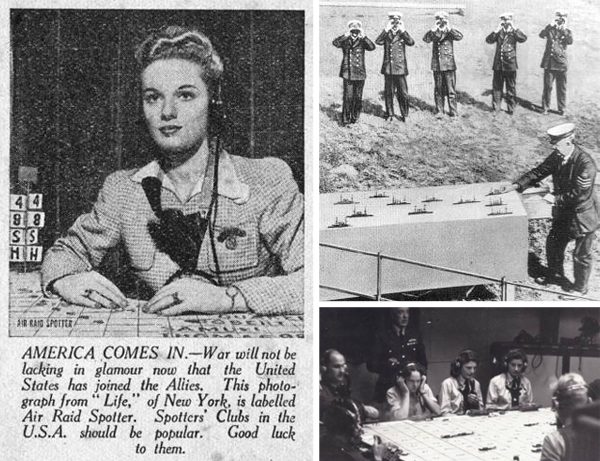

Finished models were used in military settings to teach soldiers how to quickly identify all kinds of aircraft. But they also helped train civilian spotters — domestic volunteers who watched the skies and tracked planes, friendly or otherwise, across coastal U.S. airspace.

Early 2D Recognition in World War I

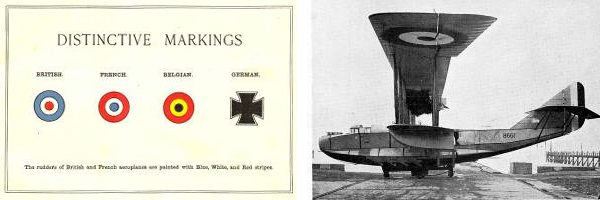

Heading into the Great War, British pilots were expected to distinguish friendly planes from enemy aircraft by markings and colors alone. As aerial warfare developed, the shortcomings of this approach quickly became apparent — aerial German attackers were sometimes mistaken for friendlies, while French allies were shot down by mistake.

According to a 1917 British spotting guide, “Even a moderately trained observer should be able to distinguish between a hostile and a friendly machine at a distance of not less than 5,000 yards” — essential for machine gun detachments — “whilst for anti-aircraft artillery work it is essential that on a clear day planes should be identified at ranges of not less than 10,000 yards,” a distance of over five miles.

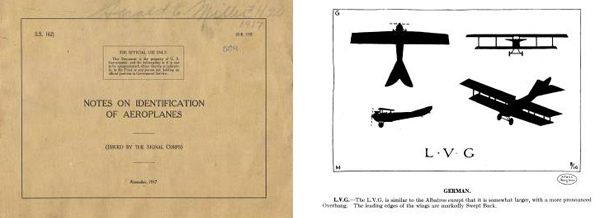

This level of recognition required shape-based identification, which, in turn, led to training with photographs and drawings (often silhouettes from the top, front, side and other angles). And while some models emerged during the First World War, it wasn’t until the Second World War that three-dimensional recognition education really took off.

The Rise of 3D Models in World War II

A 1944 edition of Flying magazine explained the significance of recognition in an age of aerial warfare: “In other wars it had not been an important factor. Soldiers in the War Between the States had only to recognize the color of the enemy’s uniform and begin shooting.”

“A vague knowledge of what the speed of the airplane was introducing into modern warfare was picked up by recognition experts in World War I and a few pamphlets were published. But until the shooting began in World War II nothing of importance was done about the recognition problem and nobody considered it important.”

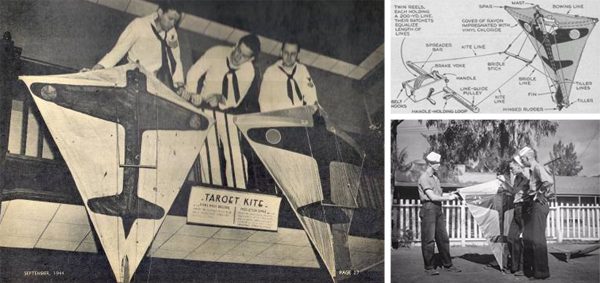

The Second World War saw the rise of recognition in both civilian and military contexts. Disney made identification training videos using models. Tru-Vue Stereoscopes showing planes in 3D sold by the millions. Target kites with plane illustrations began to take flight.

Commercial spotter games emerged as well, ranging from identification card decks to tabletop boards like Spot-A-Plane, in which players advanced in part by correctly recognizing specific aircraft.

And while the U.S. Navy itself never officially used games to train troops, the lines between play and war did blur in the realm of modeling — manufacturers sold 1:72 scale mockups identical to those designed for training purposes. In Britain, many children who built models as part of the “Skybird League” during the interwar period went on to become Royal Air Force fighter pilots in the Second World War.

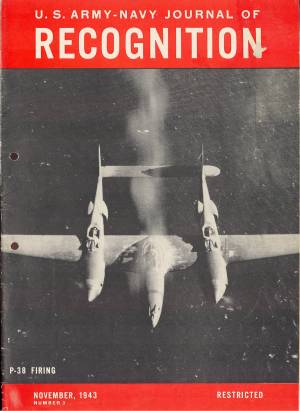

For training purposes, models were especially important — per the U.S. Army-Navy Journal of Recognition, it was critical that observers be able to see an “object as a whole” and be “able, through constant practice, to recognize that object (plane, tank, ship, etc…) from any angle.”

For training purposes, models were especially important — per the U.S. Army-Navy Journal of Recognition, it was critical that observers be able to see an “object as a whole” and be “able, through constant practice, to recognize that object (plane, tank, ship, etc…) from any angle.”

Initially, the parts-based WEFT recognition system (standing for: wings, engine, fuselage and tail) dominated training, but it was time-consuming — observers had to recognize then mentally assemble parts to determine the whole. This approach was subsequently discarded in favor of a total-perception view of recognition, aimed at speeding up the identification process by tapping into innate pattern-recognition capabilities. The Journal of Recognition also published regular issues to help keep readers up to date on changes in aircraft design.

Recognition training was naturally useful in more active theaters of the war. But after German submarine attacks on the East Coast and Japanese shelling on the West Coast, it was also seen as essential for Ground Observer Corps volunteers on the U.S. mainland.

As the war continued, school-based model-making made its way beyond the United States, both north to Canada (where children made models for the Royal Canadian Air Force) as well as south to Ecuador, Guatemala, Chile, Colombia, Peru, Uruguay and Brazil.

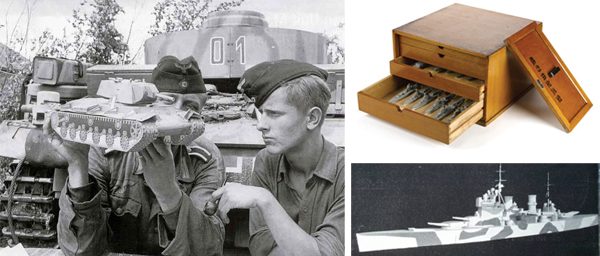

Like Allied forces, Axis powers also modeled vehicles of war, including (and beyond) airplanes. Above: a field-assembled German tank model, box of Japanese wooden ship models and a dazzle-painted vessel.

As the more and more Americans traveled to meet up with British allied forces and help retake Europe, recognition training was expanded via the Inter-Service Recognition Committee. In preparation for the vital Operation Overlord (codename for the Battle of Normandy), the Royal Observation Corps trained Seaborne Aircraft Identifiers to serve with the U.S. and British Navies — recognition became a shared endeavor of the Allies for and beyond D-Day.

Comments (1)

Share

One maker of “teacher models” during WWII was South Salem Studios, a tiny shop in tiny South Salem village in Westchester County NY. Read about it in one of those little Images of America books.

(Incidentally anyone interested in roads and bridges should check out the Merritt Parkway book from that same series.)