In 1975, Barbara Visser was a nine-year-old kid on a school field trip to the Stedelijk art museum when she first saw a painting titled Who’s Afraid of Red, Yellow and Blue III by the American post-war artist Barnett Newman.

What she saw was a massive canvas, nearly 18 feet wide and eight feet tall. On the left side, a small strip of blue, and on the right, a small strip of yellow. But the rest of the surface was painted entirely red. “And I got very angry,” says Visser, “I ran out of the museum. I sat on the steps and was determined not to go in again.”

This was a painting that produced such strong reactions in people that it drove them to action. Visser struggled with the painting her entire life and made a feature-length documentary about it called The End of Fear, which inspired this story. It’s about a reaction the painting received that was so intense, so violent, it set off a chain of events that shook the art world to its core.

Anybody Can Do That

Barnett Newman was a late bloomer. He was a substitute art teacher, then an art critic, and then an artist. Newman didn’t even have his first solo show until he was almost forty-five years old. Newman quickly became the de facto spokesman for a new art movement called Abstract Expressionism.

Abstract Expressionism came out of New York in the 1940s. The movement produced painters like Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, and Helen Frankenthaler. These artists were known for big canvases full of wild colors, shapes, and splashes of paint. Like many abstract expressionist artists, Newman saw his work as a reaction to the horrors of World War II. For Newman, figuring out what a painter could do after witnessing events such as the Holocaust and the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki required ignoring all of art history and starting over from scratch.

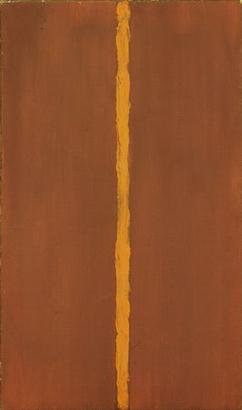

He began making large paintings that were big even by abstract expressionist standards. They could often fill the entire wall of a gallery. They usually featured very few colors — usually one solid hue broken up by a few vertical stripes which Newman referred to as “zips.”

In 1967, Newman finished what would prove to be one of his largest paintings: Who’s Afraid of Red, Yellow, and Blue III.” It was the third in a series, and the title was a reference to Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf, the landmark play, which later became a movie starring Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton.

Barbara Visser says that when the Stedelijk Museum acquired Who’s Afraid of Red, Yellow, and Blue III in 1969, a lot of people did not like it. “At the time people would write really long and elaborate letters to say how much they hated this painting,” she recalls. The painting elicited the kind of response that a lot of people still have to abstract art — questioning why this constituted art at all when it seems as though anyone could do that. One woman even expressed that it literally made her sick.

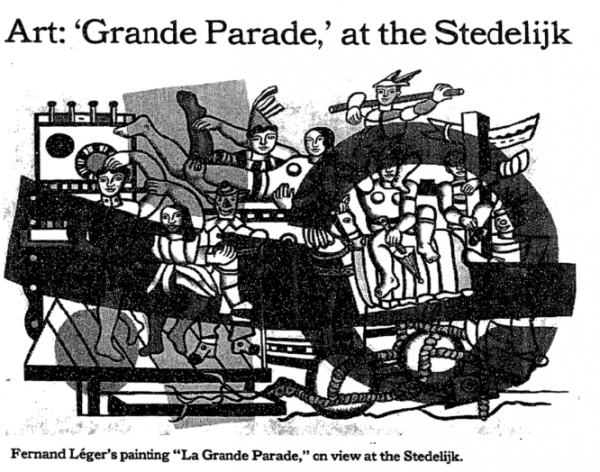

In the 1980s, the painting was the centerpiece of an exhibit at the museum called the Grande Parade, the purpose of which was to raise exactly this question of what a painting is or isn’t. This was when the negative opinions of Who’s Afraid of Red, Yellow, and Blue III were taken to a whole new level.

The Murder of Who’s Afraid of Red, Yellow, and Blue III

While the painting was on display, a man named Gerard Jan van Bladeren attacked Who’s Afraid of Red, Yellow, and Blue III with a box cutter, tracing a series of long slashes through the center of the canvas. When the slashes were added all up together, they measured nearly fifty feet long. Van Bladeren was 31, unemployed, living with his parents, and was a painter himself — although not very successful. He regarded this act of vandalism as an artistic gesture. He saw the painting as a kind of cultural provocation, and one of the main arguments that his lawyer made in his defense was that this provocation called for a reaction and got one.

Van Bladeren was sentenced to five months in prison, and stood by his actions as a defense of artistic values. Many people in the Netherlands agreed and sent letters to the Stedelijk. “This so-called vandal should be made the director of modern museums,” read one. “He did what hundreds of thousands of us would have liked to do,” read another.

The Rules of Restoration

Carol Mancusi-Ungaro is one of the leading experts in the field of art conservation. Mancusi-Ungaro has pioneered techniques for restoring work by modern and contemporary artists and has worked on several paintings by Barnett Newman. She says that there are a set of rules that conservators must follow when restoring a painting, the first being that you should make every effort to not use any material that cannot be removed or reversed in the future.

If conservators add paint to a canvas, they want to make sure that paint can be dissolved and removed later. They do this in case the artwork needs to be retouched again in the future. Conservators also try to preserve as much of the original material as possible, touching only the areas that need treatment. They should also really study the artist and look at their past work in order to get a sense of what the artist was trying to achieve.

With these rules in mind, the Stedelijk phoned up practically every conservator in Europe. The biggest challenge was the very simplicity of the painting. The busy texture and detail of a Picasso or a Rembrandt often help to mask repair work, but Newman’s canvas was mostly just one big swath of uniform color, so any sign of repair would stand out.

Daniel Goldreyer was a conservator based on Long Island who had worked with Newman while he was still alive who said he could repair the painting within 98% accuracy. Goldreyer promised that when he was done, the slashes would be virtually invisible. The officials at the Stedelijk breathed a sigh of relief, and in 1987, Who’s Afraid of Red Yellow and Blue III was rolled up, put in a narrow, coffin-like box, and carried solemnly down the steps of the museum and shipped off to Goldreyer’s studio in New York.

Murdered! Again!

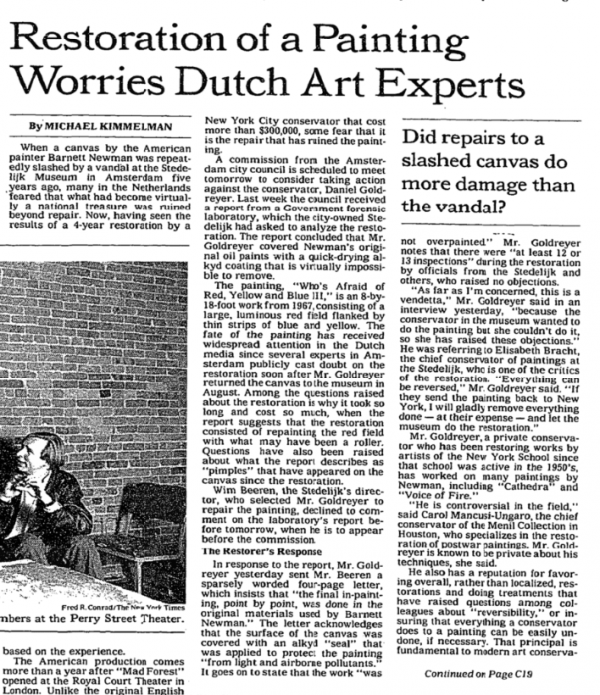

Finally, four and a half years later, Goldreyer unveiled the painting, and when the museum director, Wim Beeren, came to inspect his work, there was no sign of the slashes. Who’s Afraid of Red, Yellow, and Blue III was headed back to Amsterdam. But when the painting went back up, people immediately noticed that the red paint looked different. It was the same hue as before, but previously there had been a shimmering quality to the red that gave it a sense of depth. All of that was gone, replaced with flat-looking red paint that, according to the restoration’s critics, robbed the painting of its original power. The city council of Amsterdam sent it to a forensic lab to try to figure out what Goldreyer had done, and they concluded Goldreyer had used a paint roller to lay down layers of dull acrylic paint similar to house paint over the original. If the analysis was correct, Goldreyer had rolled over the entire canvas of a twentieth-century masterpiece with house paint. Who’s Afraid of Red, Yellow and Blue III had been murdered… again.

Goldreyer insisted that he hadn’t painted over the canvas and instead said he had pinpointed the red part with two million tiny dots. Although forensics refuted this, Goldreyer sued for defamation and the museum settled because the museum’s director had previously signed off on the restoration. The whole affair cost over a million dollars and now the museum was still stuck with a damaged painting.

Return of the Art Killer

In 1997, eleven years after the slashing, van Bladeren found out about the botched restoration of Who’s Afraid of Red, Yellow, and Blue III, and returned to the museum to do it again. Van Bladeren returned to the museum searching for Who’s Afraid of Red, Yellow, and Blue III, to slash once more, but fortunately, the painting was not on display at the time. Van Bladeren found another piece by Newman, a large blue painting with a white zip down the middle titled Cathedra and attacked this piece with a box cutter. When he was done, he threw a packet of pamphlets on the floor that contained rambling, incoherent writing. At his second trial, van Bladeren was declared mentally unfit and sent to a psychiatric institution.

A History of Art Vandalism

These particular attacks were motivated by mental illness, but they’re also part of a long, sad history of art vandalism. Picasso’s Guernica was spray painted in the 70s; acid has been thrown at Rembrandt’s artwork; and two Michelangelo sculptures have been attacked with hammers. Newman’s work, in particular, has been vandalized several times for anti-semitic reasons. Newman was a Jewish artist and Who’s Afraid of Red, Yellow and Blue IV (which was the sequel to Who’s Afraid of Red, Yellow, and Blue III) was struck and spat upon in Germany, because the attacker said it bore a mocking resemblance to the German flag. A Newman sculpture at a museum in Houston was spray-painted with swastikas in 1979 and just last year, someone poured white paint into the reflecting pool surrounding this same sculpture and left behind white supremacist leaflets.

After Cathedra was attacked, both Ysbrand Hummelen and Carol Mancusi-Ungaro advised on its restoration, and the museum spared no expense. The canvas was stitched together with surgical sutures and orthodontic wire on a specially built table. Four painstaking years later, it was unveiled. It’s not perfect — if you look closely, you can see the scars, but the impression survives.

Cathedra is currently on display at the Stedelijk. But not Who’s Afraid of Red, Yellow, and Blue III. The painting is in a storage facility at the edge of town. It waits there, hoping for a day when future conservators might be able to undo what was done to it. To remove the layers of paint, and get to the original experience, the one the artist created, still sleeping underneath.

Comments (7)

Share

Reminded me of the Rothko tag (Tate Modern)

https://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/art/art-news/9592962/Rothko-painting-vandalised-in-Tate-Modern.html

A look into the conservation of Rothko’s piece after that attack. https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=AGqAggmwyMU

Dear 99PI’ers –

I just finished listening to The Many Deaths of a Painting while on my run. Another great episode.

However, I was saddened by a moment in the show when Barbara asks John how he would feel if someone attacked a painting after they heard this podcast… John responds that he would feel terrible and that the episode would have failed. While I empathized with John in that moment and his reaction is genuine, I really feel the query was unfair. The question ties into a longer history of creation, causation and correlation. And frankly, it gets to the heart of the episode itself. Would Newman not have painted if he knew his works would be slashed. I would guess he would paint without fear. I don’t think denying the making or talking about a thing does anything but smother thought, conversation (this of course does not include hate speech and the like). This podcast informs, enlightens, and surprises. Keep doing that!

A loving listener,

Robert

Hi, I was very happy to hear my profession of conservation given such a stellar spotlight. I would ask, however, that if you’re going to expound upon how “cool” our work is, that you also acknowledge how undervalued we are. Conservation takes intense and niche training, often at significant cost to the practitioner. Once that training is completed (undergrad, grad school, fellowships), jobs are few and far between, and pay is not comparable to the cultural value of the work, nor the investment conservators must make to become experts. There are, of course, individuals in our field who make a decent wage, but many do not, and even more end up pursuing other careers because of the financial burden the field places on us. Again, I’m glad the podcast was able to give a wider audience an understanding of this field of study that I love. Thanks for a great episode. But let’s talk about the less sunny side of this as well. Eddy

Why not just leave it and let people see the consequences of the person’s actions?

There’s something about art restoration that is deeply satisfying, especially that comforting, reassuring feeling that watching a good restorer at work brings – the feeling that someone has all the bases covered, that there are materials, techniques and procedures for every eventuality, and that all of them guarantee that the work of art’s original artistic vision will be preserved, that all the work done can be reversed if needed, and that it will remain stable and unchanged for many years to come. Julian Baumgartner has a really good channel on YouTube, showcasing many of his conservations step by step, I highly recommend it.

I am intrigued by the desire/option of the history of a painting to be obliterated/disguised rather than used as a story line. In Japanese culture the history of a piece of ceramic is celebrated with a gold repair. I understand that it is a different medium, but is there not a comparable option with painting?