The use of checkered patterns by police forces has roots in Scottish heraldry, traditional tartans, and one particularly progressive police chief in northern Britain. Per the Glasgow Police Museum, it started like this: “Around the time of the First World War and shortly thereafter, a number of Scottish Police forces, whose officers wore black peaked caps, sought ways to make their officers easily identifiable from the bus drivers and other local officials, who wore identical caps.” [Note: This was adapted from part of a story in the book: The 99% Invisible City].

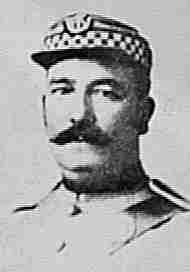

At first, officers just added white cap covers in order to stand out, but these got dirty too easily. So, in the 1930s, police in the city of Glasgow, Scotland began using a black-and-white checkered pattern to distinguish themselves from other public servants who wore otherwise similar hats. This specific pattern was brought into the realm of law enforcement by Chief Constable Sir Percy Sillitoe.

At first, officers just added white cap covers in order to stand out, but these got dirty too easily. So, in the 1930s, police in the city of Glasgow, Scotland began using a black-and-white checkered pattern to distinguish themselves from other public servants who wore otherwise similar hats. This specific pattern was brought into the realm of law enforcement by Chief Constable Sir Percy Sillitoe.

At his post in Scotland, Sillitoe would make a name for himself by breaking up the city’s notorious Glasgow “razor gangs” and modernizing his police department with wireless radios. He would later go on to become the Director General of MI5, the United Kingdom’s internal security service. None of that, however, left a legacy as visible as his influential introduction of a simple tartan-style pattern to the world of modern policing.

At his post in Scotland, Sillitoe would make a name for himself by breaking up the city’s notorious Glasgow “razor gangs” and modernizing his police department with wireless radios. He would later go on to become the Director General of MI5, the United Kingdom’s internal security service. None of that, however, left a legacy as visible as his influential introduction of a simple tartan-style pattern to the world of modern policing.

“Strictly speaking,” clarifies the Scottish Registry of Tartans, “it isn’t a tartan and Sir Percy Sillitoe … didn’t design it.” In fact, “it had existed for about 100 years as a Heraldic symbol in many Scottish coats-of-arms.” Moreover, “Highland soldiers are said to have woven white ribbons into their black hatbands, thus creating a chequered effect” long before anyone thought to mimic the appearance on police hats. From these traditional glengarry bonnets came the design used by officers under Sillitoe’s watch, which likewise featured a checkered pattern three rows high and wrapping around a cap.

“Strictly speaking,” clarifies the Scottish Registry of Tartans, “it isn’t a tartan and Sir Percy Sillitoe … didn’t design it.” In fact, “it had existed for about 100 years as a Heraldic symbol in many Scottish coats-of-arms.” Moreover, “Highland soldiers are said to have woven white ribbons into their black hatbands, thus creating a chequered effect” long before anyone thought to mimic the appearance on police hats. From these traditional glengarry bonnets came the design used by officers under Sillitoe’s watch, which likewise featured a checkered pattern three rows high and wrapping around a cap.

Variations on the so-called Sillitoe Tartan have since spread to police and emergency services across the UK, as well Brazil, South Africa, Iceland and other countries around the world. In some places, the basic pattern is still black-and-white or blue-and-white, but there are myriad other color combinations that vary from place to place.

These patterns are often used by emergency services on official garments including hats, vests, and vehicles. Different colors can also convey different specific information, with meanings that vary on state and local levels. In Australia, blue-on-white checkerboard patterns have been used by state, territory, national and military police vehicles — even the official flag of the Australian Federal Police (above) is wrapped in a Sillitoe band. Meanwhile red, yellow and orange combinations have been used by other emergency services to distinguish their purpose. Departments of transportation and corrections as well as volunteer rescue organizations have incorporated variants of the Sillitoe Tartan, too.

These patterns are often used by emergency services on official garments including hats, vests, and vehicles. Different colors can also convey different specific information, with meanings that vary on state and local levels. In Australia, blue-on-white checkerboard patterns have been used by state, territory, national and military police vehicles — even the official flag of the Australian Federal Police (above) is wrapped in a Sillitoe band. Meanwhile red, yellow and orange combinations have been used by other emergency services to distinguish their purpose. Departments of transportation and corrections as well as volunteer rescue organizations have incorporated variants of the Sillitoe Tartan, too.

In Western Australia, though, at least one ambulance service has adopted a newer design approach, employing what are known as “Battenburg markings,” which can look similar to Sillitoe patterns at a glance. Like Sillitoe patterns, Battenburg markings are checkered, but instead of three rows of alternating tones they are generally limited to just one or two, with larger blocks of white, black or different colors. Sillitoe is a good “recognition pattern” but can be hard to make out at a distance. Thus, UK police developed Battenburg patterns and tested them, demonstrating they can further increase visibility as well.

Still, some emergency services departments get a bit carried away with these approaches, implementing patterns without exploring out how well they actually work, often overdoing it in the process. Patterns that are too complex can have unwanted effects, like: confusing observers. Sometimes, less is more and complexity compromises effectiveness.

Sir Percy Sillitoe helped open the world’s eyes to wider variety of options now in use globally, but cities still need to think locally, too. Rather than adopting a pattern like Sillitoe or Battenburg just because it has worked well in other places, police and other emergency departments would be well served by testing and iterating on designs.

In The 99% Invisible City: A Field Guide to the Hidden World of Everyday Design, New York Times bestselling authors Roman Mars and Kurt Kohlstedt uncover engaging stories like this about all the thought that goes designs that most people don’t think about. Over the course of 400 pages and 100+ illustrations, we explore the origins and other fascinating tales behind power grids, fire hydrants, street signs, and so much more. If you enjoyed this short story excerpt, be sure to check out the whole book!

Comments (1)

Share

Possible origin of the Battenberg nomenclature for the pattern referenced later in the article: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battenberg_cake