Back in the 1960s and 70s, in the city of Pittsburgh, there was a nickname for guys like John Moon – The Unemployables. This nickname meant that you simply could not get hired, no matter where you went for a job. Moon grew up in Pittsburgh’s largely Black and economically depressed Hill District. In better times, the Hill had its own Negro League baseball team and jazz clubs that regularly hosted Duke Ellington and Louis Armstrong. But by the time Moon was graduating high school in the late 60s, there was no escaping the neighborhood’s “unemployable” stigma. Moon was glad to land as an orderly at Pittsburgh’s Presbyterian-University Hospital, which provided steady employment, but not much else.

One night halfway through a graveyard shift, Moon watched as two young men burst through the doors of the hospital. They were working desperately to save a dying patient. Maybe today he wouldn’t bat an eye at this scene, but in 1970 nothing about it made sense. The two men weren’t doctors, and they weren’t nurses. And their strange uniforms weren’t hospital issued. Moon was witnessing the birth of a new profession—one that would go on to change the face of emergency medicine. The two men were some of the world’s first paramedics, and, like Moon, they were Black.

Whose Problem is it Anyway?

Richard Clinchy is the president of the EMS museum and a trained paramedic, and he says that when he started in emergency care in the late 50s, there wasn’t really any infrastructure in place created with emergency medicine in mind. “In my early days in EMS, for example, emergency rooms weren’t open 24 hours a day. You’d have to go to a hospital and ring a bell and the security guy would have to come down to the door, open up the emergency room, then you’d have to get a doctor to come into the hospital,” explains Clinchy.

On-site medical care had been slowly developing for decades on the battlefields of Europe and East Asia, but even as late as the late 1960s, the American medical community understood so little about emergency medicine that advances on the battlefield were ignored at home.

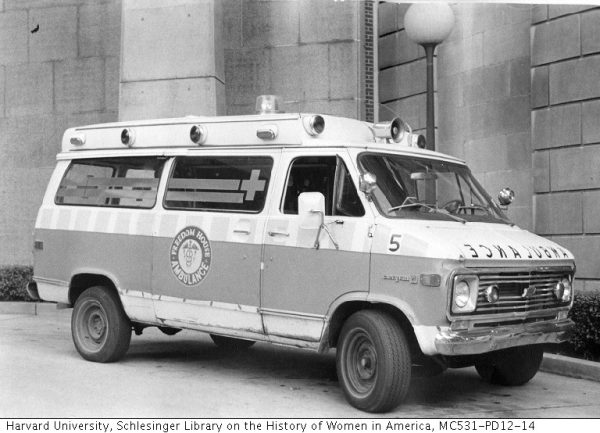

As a result, emergency services were not there to provide treatment at the scene or even necessarily on the way to the hospital… they were just about getting you to the hospital as quickly as possible. It also wasn’t clear whose responsibility it was to rush to the scene of an accident. Oftentimes firefighters were the ones to respond, and they were expected to deal with health treatment themselves. In other areas, the responsibility for transporting patients often fell to local funeral homes. In many major cities, this crucial task fell to another municipal service that probably had even less business responding to medical emergencies: The police.

Swoop and Scoop

John Moon can still remember what the emergency services provided by the police were like in Pittsburgh in the 1960s, “The public was faced with … ‘swoop and scoop’ which meant you’d call the police and they’d pick you up, throw you in the back of a paddywagon, and rush you off to the hospital.” They could do little more than offer patients basic first-aid, a canvas stretcher, a half-empty oxygen tank, and a pillow, which often only served to choke off your airway. “And on top of that,” says Moon, “both officers got up front.” The patient was left to fend for themselves in the back of the police van. If you stopped breathing in the backseat, there was no one there to assist you.

But if Pittsburgh’s services were typical of the country at the time, the emergency care provided in the largely Black Hill District was even worse. Pittsburgh’s mostly white police force was often slow to respond to emergencies in the Hill, while many Black residents, were reluctant to even call the police to begin with. No one wanted to get in the exact same police van the cops had threatened to throw them in yesterday. For Moon and others in the Hill District, the police weren’t just bad at providing emergency medical care, they were the wrong people for the job, and the same was true to varying degrees in the rest of the country. Whether a neighborhood was served by the police, the fire department, or the local funeral home, so long as the priority was transportation as opposed to treatment, no one even realized there was a “job” that needed doing.

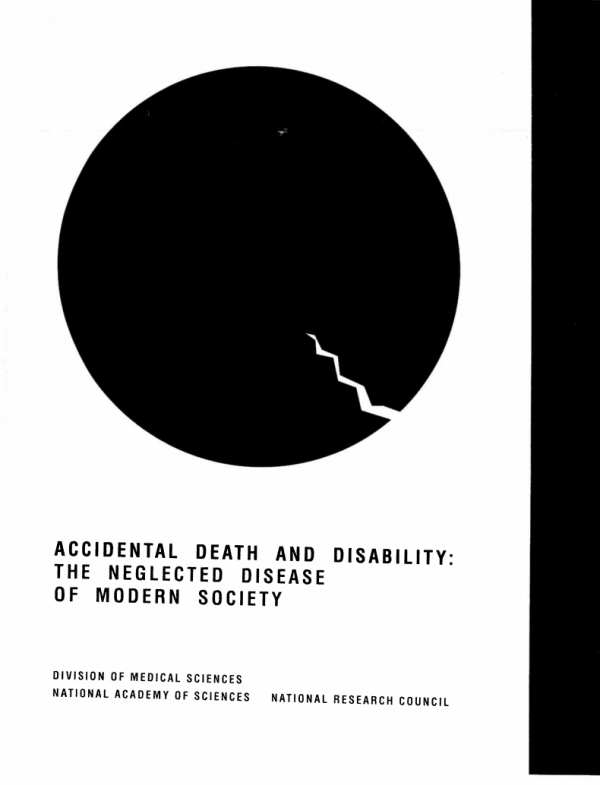

The White Paper

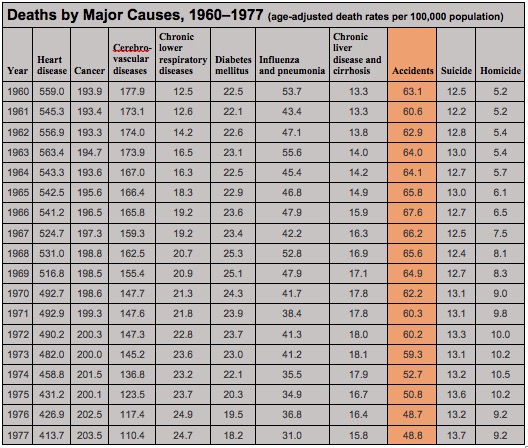

But then in the mid-60s, something called the White Paper flipped the paradigm for emergency care on its head. In 1966, the federal government published a paper that reported that as many as 50,000 deaths a year could be attributed to pre-hospital care. According to the White Paper, not only were ambulance crews providing poor care in the streets but too often there wasn’t a hospital within driving distance capable of handling a critical patient. The fatality rate for people suffering from gunshot wounds in the US was even worse than those in the Vietnam War. Facts such as these shamed the government into providing money for EMS development on the local level. Newly flush with cash but not sure exactly how to spend it, government officials and local community leaders began searching for solutions.

Phil Hallen is a former ambulance driver who came to Pittsburgh in the early 60s where he headed a civil rights organization called the Maurice Falk Medical Fund. The organization focused on health disparities due to institutional racism, and he immediately focused his ire on Pittsburgh’s pitiful emergency services. His immediate impression was that nobody, especially the police department, was properly trained in emergency medicine. He could also see that what was going on was effectively a public health crisis that was disproportionately affecting Black neighborhoods.

One day, Hallen came across an article in the local paper, about a Black-operated jobs training program based in the Hill District called Freedom House. The article described how Freedom House had rolled out a kind of mobile grocery store for Black neighborhoods, using trucks to bring fresh vegetables to people’s doors. Hallen initially thought something similar could be done to provide medical transportation to the underserved Black communities of Pittsburgh. But then he met Dr. Peter Safar.

The Good Doctor

When Hallen met him in 1966, Dr. Peter Safar was already famous in medical circles for being the “father of CPR.” The head of anesthesiology at the University of Pittsburgh, he was already searching for a solution to the problem of poor pre-hospital care, and within seconds of greeting Hallen and the Freedom House team, the wiry and energetic Safar began to unleash a torrent of ideas.

He proposed that together they train lay people to be medical professionals who could start providing ER quality treatment right away, before the patient arrived at the hospital. Instead of repurposed cargo spaces, Safar argued, ambulances should be mobile intensive-care units staffed by professionals trained to use cardiac monitors, administer medication, and anything else that might keep a patient alive.

Safar set about designing advanced ambulances and an intense 300-hour course, whose graduates would be the world’s first comprehensively trained first responders. This wasn’t just the birth of a profession, but of a whole new branch of medicine. It would become a vital link in the chain, with a subculture all its own, and the world’s first fully-trained paramedics would be staffed exclusively with young Black men from the Hill District of Pittsburgh.

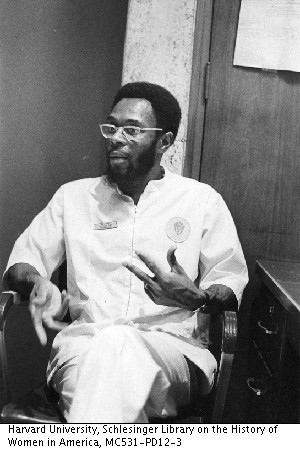

The world’s first fully-trained paramedics underwent a battery of psychological evaluations and interviews with medical professionals. They learned anatomy, physiology, CPR, advanced first aid, nursing, and defensive driving. If they were going to bring the ICU to the street, they had to master everything that happened in an ICU. John Moon wasn’t part of that first class. He joined a few years later, but he would become one of their most experienced paramedics.

Moon says Freedom House faced a number of challenges, including the police. The city had contracted with Freedom House to handle calls in Pittsburgh’s mostly Black neighborhoods and the downtown area, but the Pittsburgh police dispatchers often refused to send them. The police felt like Freedom House had taken their jobs away, but Freedom House believed that the police — with their poor training — were a threat to the patient. Moon says that Freedom House would have a police scanner on to monitor the calls and would try to get to emergency situations before the police did to make sure care was given properly. Sometimes the police would relent, but other times they would threaten the paramedics with arrest unless they backed off. Some white patients even rejected physical contact from the Black paramedics, and doctors even denied Freedom House’s help. Moon remembers trying to read a patient’s vital signs only to have a nurse laugh in his face as if he was pretending to play doctor. Other Freedom House paramedics were mistaken for orderlies and asked to mop the floor.

trained them. At front row, center, is Nancy Caroline, M.D., who developed national standards for emergency medical technicians. At far left, in white lab coat, is Peter Safar, M.D., known around the world

as the “Father of CPR.” Photo courtesy of University of Pittsburgh

Freedom House Rises

But despite all the struggle, Freedom House’s reputation was growing. By this time, Freedom House’s five ambulances were running nearly 6,000 calls a year. And not only were they getting to the patients faster than the police, but they were also providing demonstrably better care. At a city council meeting, Safar presented data showing that as many as 1,200 people a year had been dying needlessly while in the care of other emergency services. Freedom House paramedics, by contrast, had saved 200 lives in the first year alone. Doctors and medical directors from around the country flocked to Pittsburgh. Freedom House medics were invited to conferences as far away as Germany. Everyone wanted to see what they were doing and learn how they could copy it.

But in spite of its growing fame, Freedom House would eventually become a victim of its own success. Other neighborhoods were wondering why this predominantly Black community was receiving better care than theirs. And perhaps no one did more to punish Freedom House for this transgression than Pittsburgh’s mayor, Pete Flaherty. Flaherty was a fiscally conservative Democrat who went into office already believing programs using taxpayer money should be managed entirely by the city. When Flaherty took office, he slashed Freedom House’s operating budget in half. This didn’t leave enough money to cover even routine maintenance on the ambulances which were falling apart. The city’s resistance to Freedom House went further than throwing up financial roadblocks. Flaherty passed an ordinance that banned ambulances from using their sirens in certain neighborhoods, significantly slowing their response times.

In 1975, the federal government chose Freedom House to field test the first standardized training curriculum for EMS providers. And Nancy Caroline, Freedom House’s medical director, was asked to write the textbook. But years of pressure from Pittsburgh City Hall were beginning to take their toll. In 1975, Flattery struck one final blow. He announced that the city would roll out its own brand new paramedic service. Not only was the new service showered with the resources Freedom House had long been denied, but none of the new recruits were Black. Caroline got the city to hire on Freedom House’s staff, but most of them were quickly re-assigned to non-medical or non-essential duties, and even as late as the 1990s, Pittsburgh’s EMS program was 98% white.

The veterans of Freedom House would go on to influence the EMS profession outside of Pittsburgh in countless other ways. Peter Safar helped to develop another early paramedic program in Baltimore. Nancy Caroline founded the first-ever EMS service in Israel. Her textbook, titled Emergency Care in the Streets, ended up setting the standard in EMS instruction for decades.

But within a few years of being replaced by the city’s EMS service, Freedom House was more or less forgotten. In part because, like all good things, paramedics were soon taken for granted.

Kevin Hazzard originally reported this story for The Atavist Magazine. Find the Atavist at magazine.atavist.com

Comments (19)

Share

This is one of the best episodes of 99%i out there. Excellent reporting, gripping topic, beautiful storytelling and delivery. Thank you for your hard work Roman & team.

Amazing story. Thank you so much for it!

My sister is a social worker who responds to police calls with (or before) the police when they are called. It is exactly the kind of job Roman was speculating about at the end of the episode. It has been a growing movement in several jurisdictions. My sister works in Utah County, Utah.

This was an amazing story. I grew up partly in Pittsburgh in the 1980s, and I’m ashamed to say that I never heard about this piece of history. Thank you much for such an eye opening piece.

In response to the afterword about possibly having some sort of police-less crisis response: many cities already have this. The longest running is based in Eugene, Oregon called CAHOOTS, but there is even one in beautiful Oakland, CA called MACRO.

Here is a good article about it:

https://www.hcn.org/issues/52.7/public-health-theres-already-an-alternative-to-calling-the-police

CAHOOTS stands for Crisis Assistance Helping Out On The Streets. It started about 30 years ago connected with White Bird Clinic. Peter DeFazio and Ron Wyden are pushing a bill to bring programs like it to other states. Look it up. It includes a licensed social worker, and a paramedic. They work cooperatively with the police. You can thank White Bird and the Buckley House Detox Center for the idea!!! (I’m very proud of my friends who started this program).

Oh, Well. I knew this story. Nancy was a very good friend of my family. Nancy was the mother fonder of EMS and paramedic in Israel. Peter Safar, A great friend. Actually, I find the movie on his experiments in a storage place of MDA – The Israeli EMS. And send a copy to Safar and the museum of anesthesia.

Nancy after retiring from the EMS, started a fellowship in Oncology and established a Hospice in the north of Israel. She wrote a book in palliative medicine. After her early death ( at 55 ) she donates all her books to me and to the Hebrew university. Her picture is on my table. It was a great loss. Her mother died 15 years later at around 95 years old. Thanks for this wonderful story and pictures. When her coffin arrives from Israel to Boston, at the airport a convoy of ambulances with “freedom house” members were waiting for her….

A few moments before the end, there is a discussion of the possibility of, basically, mental health EMS. Well, that very thing is in the works in none other than Alameda County (home of beautiful downtown Oakland California) and will be hitting the streets soon.

I’m disappointed that Roman propagates the confusion between the two-snake Caduceus and the one-snake Rod of Asclepius. I think a correction is warranted.

I agree! 99pi, of all places, should get it right.

Thank you for covering this amazing, inspiring story! It deserves to be better known.

If the streaming services are looking for new material, they couldn’t go wrong to develop a series from this story.

Great show! I heard this not long after listening to a BBC Witness History episode about the invention of the portable defibrillator for heart attacks which also changed procedures for ambulances so that medical care was given at the scene rather than after transport to a hospital, by which time it was often too late: https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/w3cszmty

That story should result on a great movie. Netflix, open your eyes!!!

H. James Lucas beat me to it – I’m a few weeks behind on my listening.

In the audio version of this story, Roman speaks of the Caduceus being the traditional symbol of medicine, or something like that. It is anything but, and if you look at the emblems on a modern EMS vehicle, you will see, instead, the Staff of Asclepius.

This confusion became a common feature of American medicine in

the 1900s as the US Army Medical Corps adopted the caduceus as its

symbol.

The original symbol of medicine is the Staff of Asclepius[1], Asclepius being the ancient Greek god of medicine, who was taught the sacred healing ways by Chiron, the

centaur[2]. The myth is that Asclepius had been kind to a snake, who in

gratitude licked his ears clean so that he could understand the snake,

who gave him healing wisdom. Throughout the period some Asclepian

healing temples would allow certain snakes to live in the building and

writhe between the injured and sick. Anyhow, the Staff of Asclepius is

just a walking stick with a single snake wrapped around it.

Contrast that to the caduceus[3]. The caduceus has two snakes wrapped

around a short staff with wings at the top. This symbol comes from

Hermes, the trickster and messenger god (sort of analogous in some ways

to Loki in Norse mythology). The thing is that he’s the god of commerce,

thieves, and fraud. He’s the clever god that’s always deceiving people.

He’s fascinating and interesting but not the connection we should be

lionizing in medicine (although with the way things are going… still,

I’d rather we move back).

Although these have been mistakenly interchanged earlier than the 20th

century, the confusion became a common feature of American medicine in

the 1900s as the US Army Medical Corps adopted the caduceus as its

symbol[4]. I’ve seen it in other countries too but the US is definitely

the worst in getting this wrong. The Medical Corps tried to justify it

on other grounds but I still think it was a poor decision.

[1]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rod_of_Asclepius

[2]: Chiron himself has his name immortalized in surgery. One possible

etymology of the world is Chiron –> chirurgeon –> surgeon.

[3]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Caduceus

[4]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Caduceus_as_a_symbol_of_medicine

Great story – always learn something new and newsworthy from your podcast. Regarding the final segment of the podcast – check out Cahoots which was founded in 1989 by the Eugene Police Department and Whitebird Clinic.

The measure of a great episode is not only learning something fascinating but also that you can’t wait to tell others what you learned! Hit this one out of the park. While we’re debating Greek, kudos.

Thank you so much for this story. Nancy Caroline was my father’s sister, and listening to this episode, I realized how little context I had for what I knew of her early work. Like so many stories, these were told to me in the framework of family history, so I didn’t know anything about the pioneering nature of Freedom House’s work. Such a delight to stumble over this information!

An interesting story. I am impressed with the drive these people had to advance the treatment of the ill, injured and dying. It is worth noting that training ambulance attendants with medical knowledge is documented back as far as the 1890s in Canada . https://www.ontarioparamedic.ca/before-9-1-1/history-of-paramedics-in-ontario

This is amazing, as a Paramedic from the U.K. I knew some of this history and have taught some of the history of this but I loved every minute of this episode and learned so much new stuff I will include in my teaching, thank you all for doing some an amazing job