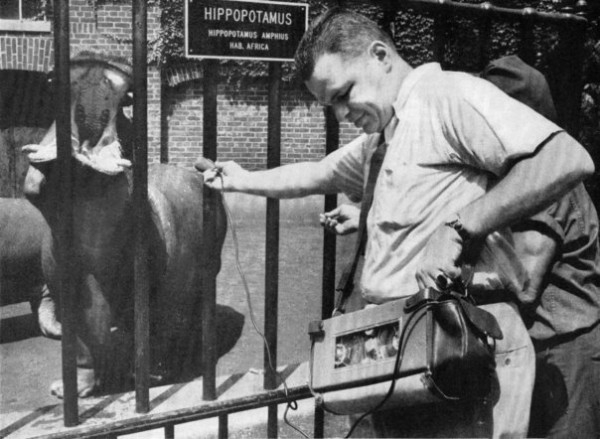

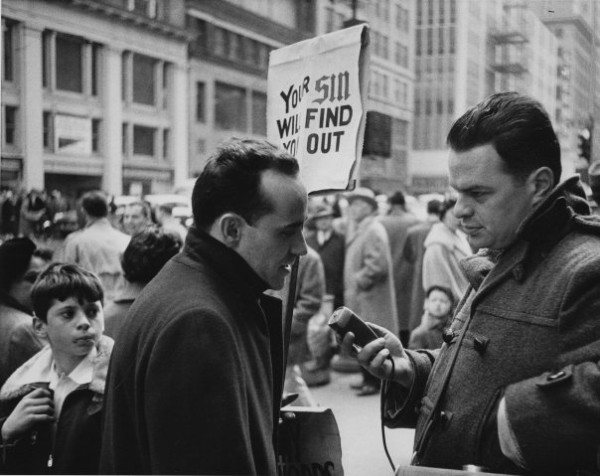

The first portable audio recorder was made in 1945 by a man named Tony Schwartz. He moved the VU meter from inside of the unit to the top, so he could see the recording volume. And, he put a strap on it so that he could hang the device over his shoulder. Armed with his recorder (and sometimes a secret microphone attached to his wrist), Schwartz chronicled every sound in his Manhattan neighborhood. He recorded children singing songs in the park, street festival music, jukeboxes in restaurants, vendors peddling vegetables, and more than 700 conversations with cab drivers, just to name a few examples.

He chronicled his niece from the time she was a baby to the time she was thirteen, and condensed the footage into an “audio time-lapse.” He also recorded his daughter as she grew, and kept a microphone over her cradle. He released 14 records of his sound collections, including a whole record of the sounds of sewing, and had a free-range weekly radio program on WNYC for more than 35 years.

As insatiably curious as he was, Tony Schwartz didn’t travel. He was severely agoraphobic. So, limited to his own hometown, Schwartz used audio to communicate with the rest of the world, exchanging audio recordings with people in other countries. Eventually Schwartz amassed a huge collection of more than fifteen thousand recordings of conversation, folklore, and folk music, which he then shared with his listeners. He introduced Harry Belafonte to Jamaican music, gave African music to the Weavers, and created a global sound exchange, all from within the few blocks he felt comfortable traveling.

Before Tony Schwartz was another innovator in broadcasting. Among the first to use the term “broadcast,” actually: Frank Conrad. The man who helped turn radio from a one-to-one communication system into a form of transmission off words, music, and art.

The sounds that came out Frank Conrad’s Garage in 1919 and 1920 are gone. There were no recordings made, and everyone who participated in his audio experiments have died. In this piece, Radio Diaries uncovers what might have happened in Frank Conrad’s garage, where some people say modern broadcasting began.

Comments (9)

Share

Roman! What’s the song in this show that starts at about the 1 minute mark? It starts right at the end of the transmission collage.

Your show is incredible

Untitled track 2 from Odd Nosdam’s No More Wig For Ohio https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XAhdvDK-2CM (00:01 – 02:51)

Bravos, Roman. Great show. Let me suggest some good reading. Two books by the gifted Tony Schwartz: The Responsive Chord and Media The Second God.

Great question at the beginning, Roman, about which technologies have had the greatest personal impact on us. Thank you for this great work!

Why do you call it Voices in the WIRE?? Both machines you show are TAPE recorders. See the crank on the top machine? That is an Amplifier Corp of America TAPE recorder which used a spring wound phonograph motor. The tape ran from the right to the left reel because the motor spindle — being used as a capstan — ran clockwise. If you do the research I think you will find that he started his battery recording around 1952.

What is the song playing in the background at the very beginning? I can’t get it to come up on Shazam…

Episodes like this one frustrate me. They’re interesting and all, and it’s nice to learn about other podcasts that you like, Roman, but my favorite podcast is 99% Invisible. It’d be nice if these rebroadcasts were in addition to your normal shows rather than in place of them.

This was an absolutely phenomenal episode! I really appreciate the exposure to these other series, I don’t believe I would have ever tuned into them otherwise.

I think what you appreciate Dave, is Roman’s curation of fascinating topics. This episode was merely an extension of that curation.

At 22 minutes, the guy who wants recordings of the sounds of the city because he has since moved out to the country…I swear that is Stanley Kubrick talking. Any way to confirm this?

Kubrick’s voice for reference: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wvoxjkTNOXE