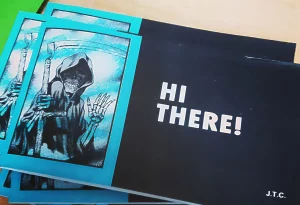

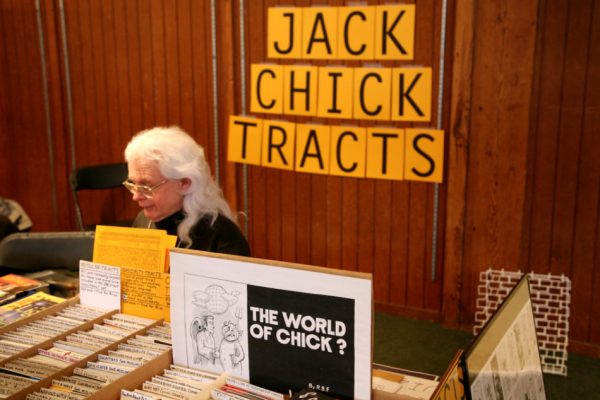

Since Chick Publications started in the mid 1960s, it has sold more than one billion tracts. There are two hundred and seventy different Chick Tracts, with titles like “The Death Cookie,” “Kidnapped!,” “Mean Momma,” “The Sissy?,” and “Satan Comes To Salem.”

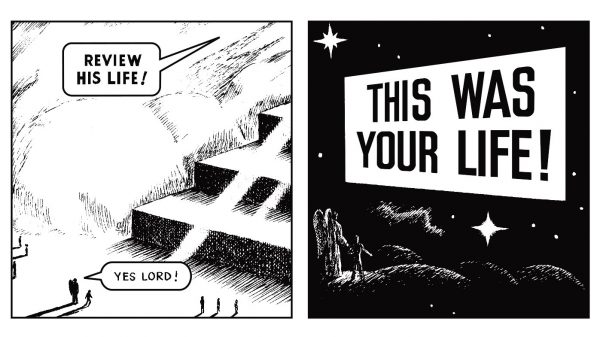

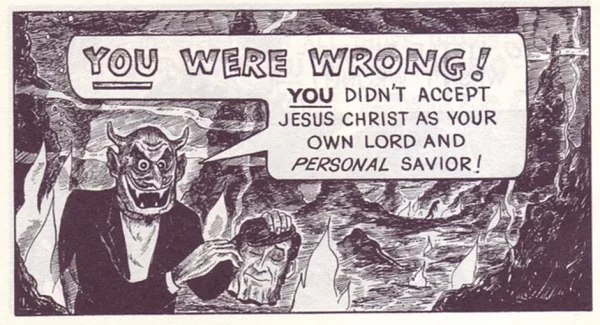

Many of these are black and white Christian horror stories that pull from a huge cast of characters: witches, bikers, Hindus, rock and rollers, Catholics, queer people, truckers, Masons and trick-or-treaters. And at some point in the tract, the protagonist often has to make a choice: either accept Jesus as their savior, or get tossed like cordwood into a Lake Of Fire.

Many of these are black and white Christian horror stories that pull from a huge cast of characters: witches, bikers, Hindus, rock and rollers, Catholics, queer people, truckers, Masons and trick-or-treaters. And at some point in the tract, the protagonist often has to make a choice: either accept Jesus as their savior, or get tossed like cordwood into a Lake Of Fire.

These little Christian comics have left a really complicated legacy. Collectors are mesmerized by their edginess and kitsch. The Smithsonian regards Chick Tracts as American religious artifacts, and keeps a bunch of them in its vaults.

These little Christian comics have left a really complicated legacy. Collectors are mesmerized by their edginess and kitsch. The Smithsonian regards Chick Tracts as American religious artifacts, and keeps a bunch of them in its vaults.

At the same time, many of these comics are filled with some ugly and dangerous messages, including homophobia and Islamophobia. So the same tracts that have been hoarded and preserved have ALSO been boycotted and banned, and condemned as hate speech.

So what is it about these tiny, inflammatory comic books that has allowed them to not just survive but spread across the planet for the past 6 decades? The answer lies in the rise of the larger than life artist behind the tracts: Jack Chick. Jack died in 2016. But in life, he was the man responsible for some of the most influential and most infamous Christian lit of the 20th century.

Jack Chick didn’t actually grow up in the church. The story of his conversion begins when he’s well into his 20s. He was a WWII vet who’d just returned from fighting in the Pacific. He was fit and confident and good-looking, with his thick dark hair and all-American jawline. Jack was also crazy in love with his sweetheart, Lola Lynn Priddle. They’d met at the Pasadena Playhouse, where Jack had a two-year scholarship to study acting. Together they dreamed of being movie stars. Jack and Lola Lynn got married in 1948. But her parents were not impressed.

Jack Chick didn’t actually grow up in the church. The story of his conversion begins when he’s well into his 20s. He was a WWII vet who’d just returned from fighting in the Pacific. He was fit and confident and good-looking, with his thick dark hair and all-American jawline. Jack was also crazy in love with his sweetheart, Lola Lynn Priddle. They’d met at the Pasadena Playhouse, where Jack had a two-year scholarship to study acting. Together they dreamed of being movie stars. Jack and Lola Lynn got married in 1948. But her parents were not impressed.

Jack was no saint before he was drafted, but while Jack was overseas he’d picked up smoking and a pottymouth. So his new mother-in-law sat him down to listen to a Christian radio program and change his ways. The way Jack tells it: as the preacher spoke, he leaned in. It was a pretty basic Christian message, but he says it rocked his world. In the decade that followed, Jack’s conversion would inspire him to change nearly everything about his life.

One of the first things he did when he got back to Southern California was rethink his dreams of becoming a movie star. As far as Jack was concerned, the Hollywood lifestyle was totally incompatible with his new faith. Instead, he leaned into another passion: art. As an adult, his art skills were alright — good enough to land a regular day job doing ads and technical illustrations in LA’s booming aerospace industry. Jack also had a couple of artistic side hustles. On nights and weekends, he did opinion and editorial cartoons for local newspapers. Plus he had a comic strip that he was really trying to get off the ground.

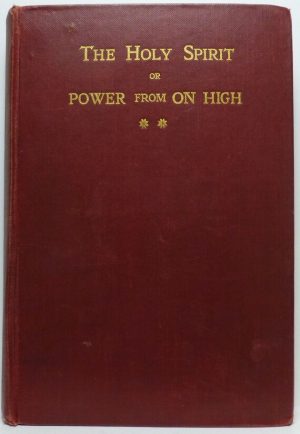

As Jack was developing his art career, he was also growing deeper and deeper in his faith. He joined a local church and started attending regularly. And then sometime around 1960, one of Jack’s coworkers – a fellow Christian – gave Jack what seemed like a pretty unassuming book. It was called “Power From On High,” and it was written by a man named Charles Finney — a 19th century minister who was a huge Christian reformer. Finney wrote that church leaders were making the whole religious experience lifeless and flat. He argued that being a Christian was supposed to be exciting and invigorating! Going to church should be a powerful experience. But complacent church leaders and their congregations were sucking the energy out of what could otherwise be a rich Christian life. That book got Jack looking at his own church with fresh eyes. And he was not happy with what he saw.

As Jack was developing his art career, he was also growing deeper and deeper in his faith. He joined a local church and started attending regularly. And then sometime around 1960, one of Jack’s coworkers – a fellow Christian – gave Jack what seemed like a pretty unassuming book. It was called “Power From On High,” and it was written by a man named Charles Finney — a 19th century minister who was a huge Christian reformer. Finney wrote that church leaders were making the whole religious experience lifeless and flat. He argued that being a Christian was supposed to be exciting and invigorating! Going to church should be a powerful experience. But complacent church leaders and their congregations were sucking the energy out of what could otherwise be a rich Christian life. That book got Jack looking at his own church with fresh eyes. And he was not happy with what he saw.

Jack felt that while he was super serious about prayer, devotion, and everything it took to be a hardcore Christian, his fellow parishioners were just pantomiming the religious life. He saw many of them as hypocrites who talked a good talk, while living ungodly lives. Worst of all: their hypocrisy was dragging the whole church down, robbing it of the kind of sacred energy and vitality that Christians call “revival”. And for Jack, this was a four alarm spiritual emergency.

Jack wanted to shake his church out of its stupor, and he thought he knew how. So he sat down with a pen and a sketchbook, and using Finney’s writings as text, he began to make his own illustrated gospel tracts. The tract was roughly the size of a typical comic book. And in it, Jack basically dragged his whole church for being a bunch of lazy and selfish hypocrites. He depicted them as Playboy-reading, rock and roll-listening backsliders who were more into their Sunday school parties than truly praising the most high.

Jack wanted to shake his church out of its stupor, and he thought he knew how. So he sat down with a pen and a sketchbook, and using Finney’s writings as text, he began to make his own illustrated gospel tracts. The tract was roughly the size of a typical comic book. And in it, Jack basically dragged his whole church for being a bunch of lazy and selfish hypocrites. He depicted them as Playboy-reading, rock and roll-listening backsliders who were more into their Sunday school parties than truly praising the most high.

“Why No Revival?” is a harsh comic critique that’s even more vicious because he used the faces of his fellow parishioners for the comic’s characters. They were not pleased, but he was excited about how much the comics stirred them up.

“Why No Revival?” is a harsh comic critique that’s even more vicious because he used the faces of his fellow parishioners for the comic’s characters. They were not pleased, but he was excited about how much the comics stirred them up.

With that experience in hand, Jack was going to use comics to reach non-Christians everywhere with a message of salvation. And he got guidance from something that was decidedly secular: a minister who showed Jack a half dozen wallet-sized comic books that he’d brought back from a mission trip to communist China. The government was using them to teach socialism 101 to its citizens, especially kids.

Around 1962, Jack got to work creating his own propaganda booklets. But instead of converting kids to socialism, Jack’s comics aimed to convert sinners to a life dedicated to Christ. When Jack first embraced his faith, he didn’t just become any Christian. He became an evangelical. And one key tenet of evangelicalism is to evangelize, to spread the faith and win converts. Jack saw himself as a soldier in a holy war. And he was motivated by his hatred of what I’m just going to call “The Sixties”. The forces of evil that Jack saw conspiring all around him were, in no particular order: equal rights for gay people, sexual liberation, the so-called divorce revolution, and the Supreme Court’s ban on mandatory prayer and Bible reading in public schools.

Jack’s aim was to rattle the cage. Like many evangelicals, he positioned himself as an embattled outsider who had no choice but to spiritually take up arms and fight. His targets included anything he associated with sorcery or the occult. He saw all of it as part of Satan’s plot to lure people away from Christ and into hell. Jack came for OUIJA boards, witches, heavy metal; Satan, obviously. Even Halloween. That dude hated Halloween.

Some of the targets of his tracts might sound ridiculous, like Jack just kinda hated fun. But he’s also made comics that are much darker, uglier, and honestly: dangerous. He depicts Muslims as demon worshippers who are inherently violent and bent on taking over America. There are more than three dozen Chick Tracts attacking Islam, Hinduism, and other faiths that Jack has labeled “false religions”.

Some of the targets of his tracts might sound ridiculous, like Jack just kinda hated fun. But he’s also made comics that are much darker, uglier, and honestly: dangerous. He depicts Muslims as demon worshippers who are inherently violent and bent on taking over America. There are more than three dozen Chick Tracts attacking Islam, Hinduism, and other faiths that Jack has labeled “false religions”.

Another of Jack’s consistent targets was homosexuality. In one of his most famous tracts, Jack goes hard on the Sodom and Gomorrah story. In another, frankly horrifying Chick Tract, he portrays homosexuality as a product of childhood rape and what some evangelicals like to call “the gay agenda.” Over the decades, Jack has been heavily criticized (and rightly so) as a purveyor of hate literature.

Another of Jack’s consistent targets was homosexuality. In one of his most famous tracts, Jack goes hard on the Sodom and Gomorrah story. In another, frankly horrifying Chick Tract, he portrays homosexuality as a product of childhood rape and what some evangelicals like to call “the gay agenda.” Over the decades, Jack has been heavily criticized (and rightly so) as a purveyor of hate literature.

For the next few years, Jack spent every second of his free time working feverishly on those comics. He would make his illustrated panels, get them printed, and then right in his kitchen he assembled the pages into 8 to 10 inch booklets — about the same size as typical comic books. By the early 1960s, The Chicks had turned their home into a kind of production center where Jack would write and draw.

For the next few years, Jack spent every second of his free time working feverishly on those comics. He would make his illustrated panels, get them printed, and then right in his kitchen he assembled the pages into 8 to 10 inch booklets — about the same size as typical comic books. By the early 1960s, The Chicks had turned their home into a kind of production center where Jack would write and draw.

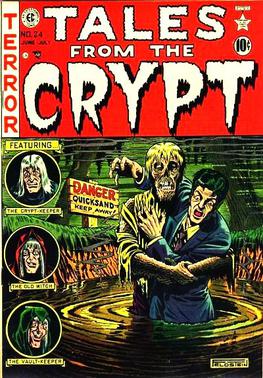

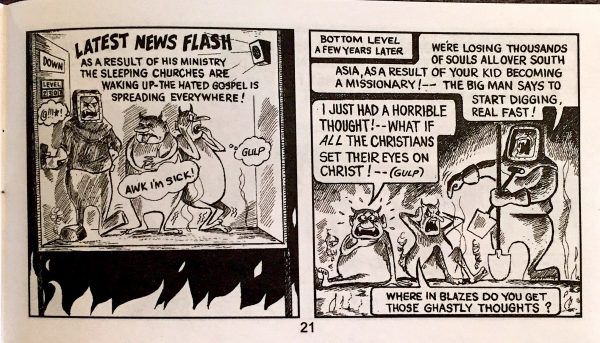

Around the same time Jack had been developing as a comic artist, horror comics like “Tales From The Crypt” and “The Vault of Horror” had become super popular. And even though Jack never acknowledged it, author and Chick expert Dan Raeburn is convinced that those horror comics had a big influence on Jack’s visual style: “It’s a very kind of 1962 vision of mainstream America, where all the adults are wearing suits and smoking cigarettes and drinking hard drinks. The demons are cartoony and the people are realistic and drawn straight. That’s the tension that makes the comic strip work, is the cartoony Hell’s minions versus the very straightforward mainstream.”

Around the same time Jack had been developing as a comic artist, horror comics like “Tales From The Crypt” and “The Vault of Horror” had become super popular. And even though Jack never acknowledged it, author and Chick expert Dan Raeburn is convinced that those horror comics had a big influence on Jack’s visual style: “It’s a very kind of 1962 vision of mainstream America, where all the adults are wearing suits and smoking cigarettes and drinking hard drinks. The demons are cartoony and the people are realistic and drawn straight. That’s the tension that makes the comic strip work, is the cartoony Hell’s minions versus the very straightforward mainstream.”

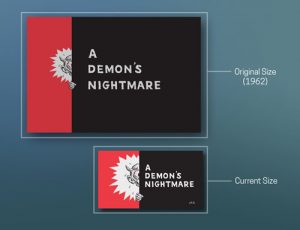

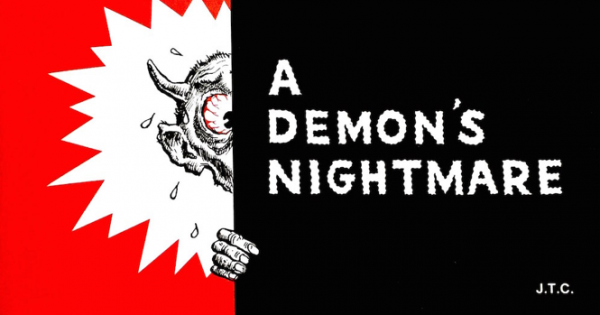

“A Demon’s Nightmare” was the first of what Jack Chick called his “soul winning tracts” — books meant to be purchased at Christian bookstores and handed out to bring non-believers into the faith. It also has the kind of weirdness that make comics comics — tropes that Jack would use over and over again for the next several decades.

The evil imps ride an express elevator back and forth between the bowels of hell and the city streets. One demon plays the violin while serenading an innocent teenager with a lullaby. If you didn’t read the text, you might even mistake it for just a regular comic.

And the cover Jack drew for “A Demon’s Nightmare” became a template for his comics. It features a two-color illustration on one half, and the tract title in bold white letters on the other half. This elegant, instantly recognizable split-cover design became the standard look for almost all Chick Tracts. In parallel, Jack’s printers had reworked their presses to fill some other specifically sized order — To keep using his same printer, Jack needed to cut his tracts by more than half: from classic comic book size down to a little under 3 by 5 inches.

Jack’s decision to cut his comic books down to pocket-size booklets helped launch Chick Tracts out into the world. He’d pioneered a successful formula by mashing up grabby, propaganda comic art with Bible verses and evangelical messaging. And then he took all that and shrank it down into these little viral packages, almost like little zines. And the newly reformatted comics were perfect tools for proselytizing.

Jack’s decision to cut his comic books down to pocket-size booklets helped launch Chick Tracts out into the world. He’d pioneered a successful formula by mashing up grabby, propaganda comic art with Bible verses and evangelical messaging. And then he took all that and shrank it down into these little viral packages, almost like little zines. And the newly reformatted comics were perfect tools for proselytizing.

Proselytizing to complete strangers was a fundamental part of evangelicalism. They call it “witnessing.” But what if your god-fearing heart was no match for your crippling social anxiety? These little comics were great for shy Christians. As a Jack Chick comic character once said, “witnessing doesn’t have to be terrifying. Chick Tracts make it EASY!”

The timing couldn’t have been better for Jack to drop his new and improved gospel comics. Jack’s redesign in 1969 coincided with some big changes that were happening in the Christian world — changes that would help put Chick Tracts in serious demand. First, American evangelicals were becoming leaders in global missionary work, and many saw Chick Tracts as vital tools for witnessing abroad. This was a period of resistance and all kinds of experimentation, and lots of evangelicals thought that the way to save souls was to lure them in with an appeal to this countercultural vibe. The long-haired, hippie preachers; the huge Woodstock-type festivals for Jesus people; and Christian rock — all of it brought to you by this evangelical revolution. As preachers tried to connect with the youth, many of them would whip out Jack’s little Christian comic books, which at least seemed to have an openness and edginess that were in sync with the times.

Orders for Jack’s tracts came pouring in. Business was so hot, Jack moved the company from his garage to an industrial suite in Pomona. Next, in order to appeal to a wider and younger audience, Jack decided to hire a more modern and more skillful illustrator named Fred Carter.

By the late 70s, Jack’s company had pushed more than one hundred million Chick Tracts out the door. There’s an old Chick Publications logo that shows the planet Earth encircled like Saturn by a ring of Chick Tracts. It’s not really an exaggeration. In the decades since Jack started Chick Publications, his cheap, very cool looking pocket-size comics reached a type of popularity that’s otherwise reserved for bestselling novels and the daily paper. Maybe bigger. A couple of years ago, the company sold its one billionth tract. Chick Publications is still going strong today, even without its eponymous leader. Jack died in 2016 when he was 92 years old.

To this day his company gets tons of orders from missionaries. Evangelicals still participate in a time-honored practice that they call “tract bombing” – where they swarm your neighborhood, sometimes at night, and flood it with hundreds of booklets on windshields and doorknobs, in mailboxes, and under your front door. And when you wake up, it’s as if Chick Tracts have rained down like one of The Ten Plagues. Chick Tracts have been an undeniable, uncontainable source of viral hate. Over the years, Jack’s focus intensified from general moral decay, to much uglier and more detailed yarns about homosexuality and pretty much all non-Protestant religions. But – there’s still something about the artist and his weird little comic books that’s interesting and even alluring, even to his critics.

In the last few decades, Jack has found a pretty big audience with folks who are actually sucked in, and even tickled, by the horrifying and self-righteous everything-phobia of Chick Tracts. On fansites, collectors have videos where they lean fully into the weirdness of Chick’s comics. To a lot of Chick Tract fans, the comics are just quaint and kitschy parodies of themselves – hilarious precisely because they’re such earnest, paranoid relics. Others see parallels between Chick Tracts and early DIY zine culture.

Jack Chick has been called a LOT of things over the last sixty years: a “lunatic Jesus freak”, a “comics scaremonger,” a “fire-breathing hell-and-brimstone preacher,” and “an underground cartooning genius.” His tracts are just as complicated: shocking, graphic, hateful – and just plain mean. And for better or worse, completely unique. It’s what drew readers to Chick tracts from the very beginning.

Leave a Comment

Share