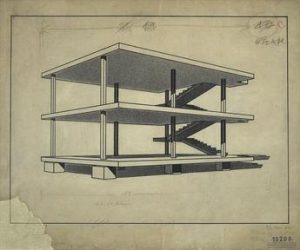

Le Corbusier was a painter, writer, architect and planner, but he was also an adept promoter of novel designs and theories. So when he debuted his Maison Dom-Ino concept home, it boasted a light and elegant form, but was also cleverly named — its title referenced the look and modularity of gaming “dominoes” (with dots extruded to form columns) as well as “domus,” the Latin word for house.

In this project, Charles-Édouard Jeanneret, better known as Le Corbusier (or simply: Corbu), synthesized prefabrication, flexibility and minimalism. The design featured thin reinforced concrete floors supported by slim concrete columns. He described his solution as “a juxtaposable system of construction according to an infinite number of combinations of plans” to allow for “the construction of the dividing walls at any point on the facade or the interior.” At a time when load-bearing walls and masonry construction were the norm, this was an unusual approach to structural engineering. It would go on to inform much of his life’s work.

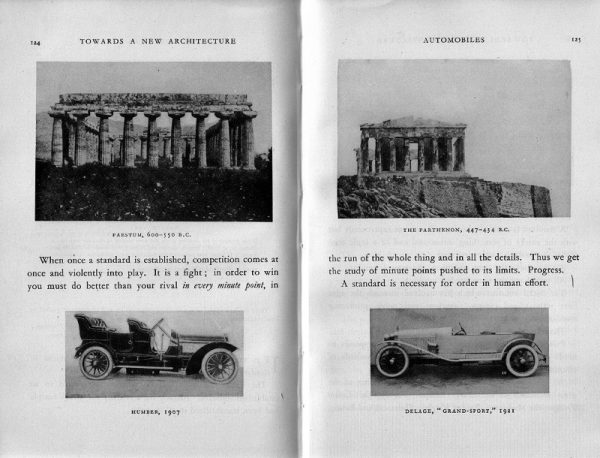

Corbu also had radical ideas when it came to architectural ornamentation, rejecting decorative traditions as outdated in the Machine Age. Critiquing the 1925 Exposition of Decorative Arts in Paris, he wrote: “The religion of beautiful materials is in its final death agony…. The almost hysterical onrush in recent years toward this quasi-orgy of decor is only the last spasm of a death already predictable.” He believed the the modern world had evolved beyond the need for decorative frills — useful, well-designed things would fill the void, not just in architecture, but for furniture, furnishings and fixtures, too.

Corbu’s views were shaped by other schools of thought (like the Bauhaus) and other Modernists, including Adolf Loos, who wrote in Ornament and Crime: “The evolution of culture marches with the elimination of ornament from useful objects.” Many prominent architects would go on to reject ornamentation, eschewing traditional styles for sleek minimalist looks, in part thanks to the writings of Loos and Corbu. In the 1920s, Corbu published his own influential book, Toward an Architecture, in which he famously wrote “Une maison est une machine-à-habiter” (“A house is a machine for living in”). It reflected his functionalist vision for the future of domestic design.

The volume also contained a critical manifesto, Five Points of Architecture. These points expanded further upon ideas he explored in the Maison Dom-Ino, laying out a blueprint for contemporary domiciles free from structural conventions and historical precedents. The five points are interrelated, and can be summarized as follows:

- “Pilotis” (columns) used to lift up buildings and create open spaces

- Free-form interior designs, enabled by structural columns

- Free-form facade designs, liberated from load-bearing functions

- Horizontal windows to provide even daylight across rooms

- Rooftop gardens on flat roofs to protect concrete and create space

Corbu also practiced what he preached. By the late 1920s he had begun work on what is now one of his most well-known projects: the Villa Savoye. It was the physical embodiment of his five points, and this video does an excellent job of showing precisely how:

Corbu lifted up and supported the structure using concrete pilotis. In turn, interior columns freed him to create open floor plans and non-structural facades with long and narrow window strips (which would have been impossible if the exterior walls were load-bearing). On top of the home sat a roof garden, conceptually: a slice of the landscape lifted up, offsetting the footprint of the house with lofted green space.

For Corbu, the interplay of masses and light made the residence beautiful — its aesthetic was a product of function and geometry. “The plan is pure,” he boasted, “exactly made for the needs of the house …. It is poetry and lyricism, supported by technique.”

From the Villa Savoye, the lineage of Corbu’s design can be traced both backward (to the Maison Dom-Ino) and forward to other now-famous works of Modernist residential architecture, including the Farnsworth House by Mies van der Rohe and the Glass House by Phillip Johnson.

But Corbu’s five points and Villa Savoye did more than just shape residential architecture — they also informed decades of urban design, and, eventually, a series of vertical urban villages in the sky.

Comments (2)

Share

Interestingly, the villa turned out to be a terrible place to live for its owners. There’s a nice bit about their experiences in “the architecture of happiness”

This man was a detriment to architecture and city planning. His buildings and his planned cities are not uplifting to behold or to inhabit. He is, in some very direct ways, responsible for the design of inner city areas that have isolated poor communities and held those people down. And while he may have personally felt that decorative architecture was some sort of bourgeois orgy or whatever nonsense language he chose to describe it, the rest of humanity (aside from a handful of other “modernist” architects who jumped on his sterile bandwagon) doesn’t agree. People don’t like walking through a neighborhood of blank, blocky towers. People don’t treasure those spaces. It’s disappointing to see you lapping up his vile rhetoric on this site.