I fell in love with architecture on the Chicago River. It provides a beautiful vantage point to take in all the marvelous skyscrapers. Unlike other cities that cram you on the sidewalk between looming towers.

The Chicago River pushes buildings apart, giving you the opportunity to really take in the city’s glory in glass, steel, and concrete.

But Chicago’s biggest design achievement isn’t a building at all—it’s the Chicago River itself.

It’s hard to tell when you see it, but the river is going the wrong way. It should flow into Lake Michigan. Instead, fresh water from Lake Michigan flows backwards into the city. The Chicago River is, in large part, a carefully-designed extension of the city’s sewer system.

Reversing the river was actually the third in a series of epic design projects spanning almost 50 years. Three projects that amounted to 19th-Century engineers fighting against the laws of nature with a kind of moxie just seems to be folded into the DNA of 19th century engineers.

The reason for the river reversal was to save Chicago from something that has destroyed cities for millennia: citizens’ own poop.

In 1854, after the city of Chicago had been growing like crazy for a couple of decades, a cholera epidemic wiped out six percent of the city.

Enter Ellis Chesbrough, an engineer from Boston. (If you’ve never heard of him, you’re not alone. At this writing, he doesn’t have a Wikipedia entry.)

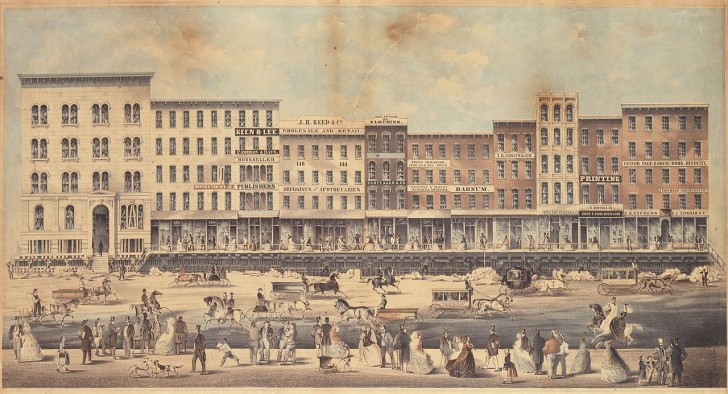

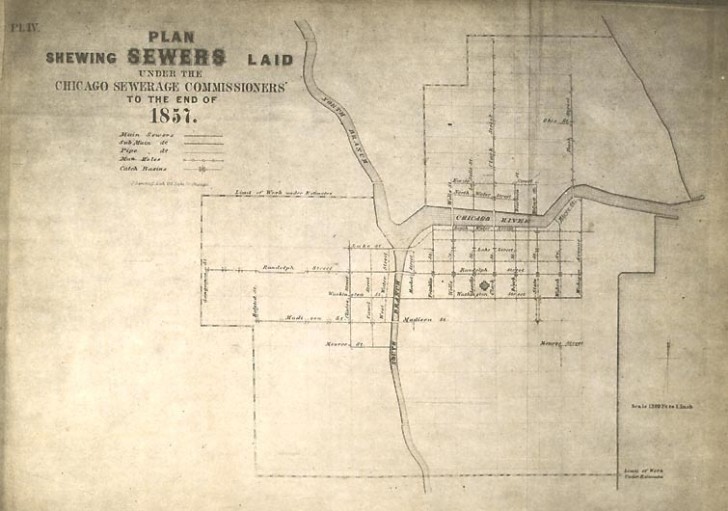

Ellis Chesbrough proposed a sewer system. It looked like this.

But there was a hitch with this plan. Chicago was too flat to allow for gravity to move waste through the pipes.

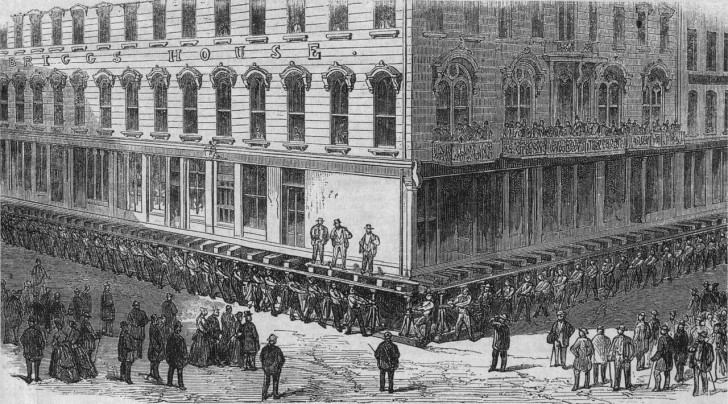

Chesbrough proposed that they jack up the street level ten feet. So they did. They put the buildings on jackscrews and started cranking.

There’s this great picture from 1857: It shows a massive hotel— big as a city block and at least three or four stories tall— with dozens and dozens of guys cranking away in perfect sync.

This kind of thing happened over and over again, all throughout Chicago. Businesses stayed open while they were getting cranked up. Meanwhile, teams of masons laid bricks for a new foundation at top speed, literally working around the guys with the jackscrews.

Here’s 35 tons worth of of stores and offices—an entire city block—getting hoisted up.

Jacking up the streets and buildings took about 20 years to finish. And by that time, Project Number Two was already done.

Not too long after the sewers went in beneath Chicago, the city realized there was another problem: waste was going straight into Lake Michigan. Which is also where Chicago gets its drinking water.

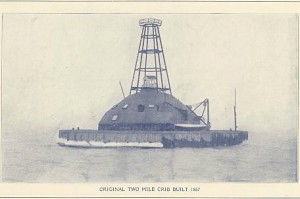

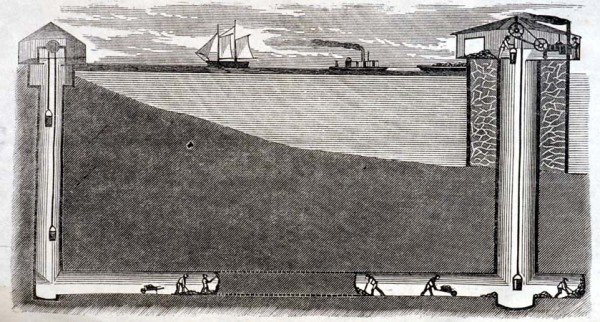

So Chesbrough has a new idea: a water intake station in Lake Michigan two miles out from shore, far beyond where it meets the Chicago River.

All they had to do to make it was build the biggest, deepest, longest tunnel that had ever existed.

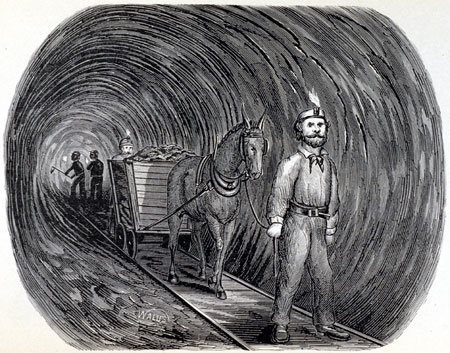

In 1864, Chesbrough’s team started digging the tunnel out from the city, 60 feet down from street level. A year later, they installed a giant structure two miles out, and then started digging a tunnel from under that back toward shore.

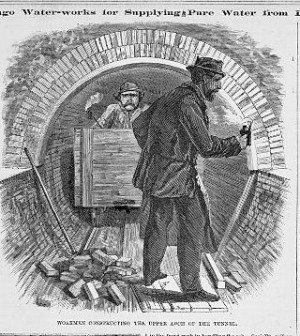

The work literally went on around the clock, from both sides: One crew dug by hand for 16 hours a day. Then a crew of bricklayers took the graveyard shift, shoring up the area that had just been dug out.

The work literally went on around the clock, from both sides: One crew dug by hand for 16 hours a day. Then a crew of bricklayers took the graveyard shift, shoring up the area that had just been dug out.

In November 1865, the two sets of crews met in the middle. The tunnels connected just about perfectly.

Chesbrough was regarded as a genius, but he still hadn’t really solved the problem. Chicago was still growing like crazy—maybe 200,000 people by 1865—and dumping more waste into the river than ever.

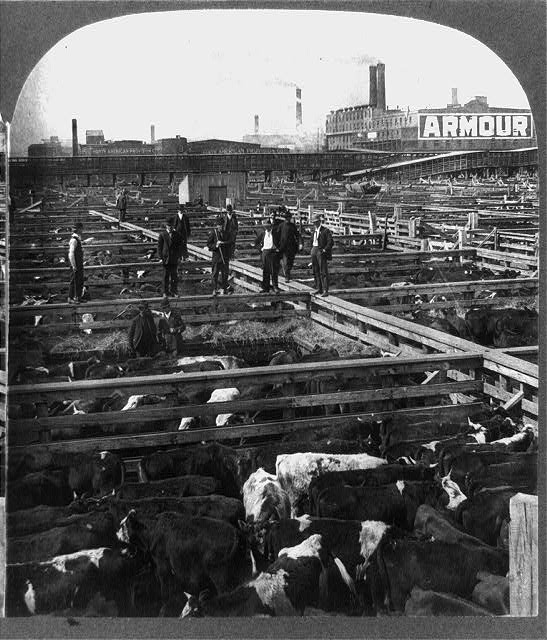

And before the water from the new intakes out in Lake Michigan had started flowing, the Union Stockyards opened on the River’s south branch. Meaning, three hundred and twenty acres of slaughterhouses and meat-packing plants were now dumping whatever they couldn’t use straight into the Chicago River. And just imagine what that would be.

That part of the river’s South Fork still goes by the name it got then: Bubbly Creek. All the discarded animal parts would rot at the bottom of the river and eventually give off methane, which would bubble up to the surface and burst. And sometimes it caught fire.

And, sometimes the dung got swept out more than two miles into the Michigan, fouling the water intakes.

Meanwhile, the city kept growing. There were half a million people by 1880, which meant even more excrement.

So Chicago started pushing for a new state law to help them undertake kind of the craziest idea ever.

They decided to reverse the flow of the Chicago River entirely.

Reversing the river would bring in fresh water from the lake, keep Chicago’s muck from polluting the drinking water pulled from the same lake, and flush all the sewage down to the Illinois River, which would flow out to the Mississippi.

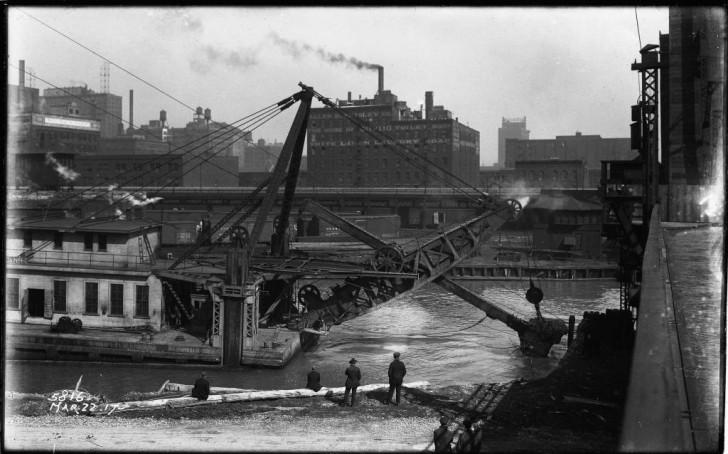

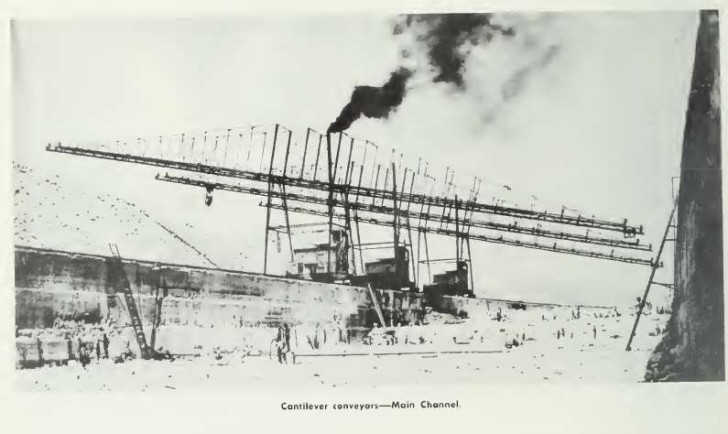

The new canal would be 28 miles long, dug out by teams of as many as 8,700 people working simultaneously, with construction going on year-round. It would take tons and tons of dynamite, and enormous machines, some specially invented for the project.

It took a few years to get the law approved — the town of Joliet saw a river of crap coming its way, and tried to nix the plan — but eventually it was “Shovel Day”: September 3, 1892. More than a thousand people came out to watch. An official took one cut with a nickel-plated shovel, and then an engineer detonated two massive loads of dynamite to create a gigantic new canal that would reverse the entire river.

It was Project Number Three in the epic struggle against Chicago’s own excreta. It cost more $31 million in 1892 money—almost $23 billion today.

During the 1893 World’s Fair, thousands of tourists day-tripped out to the construction zone.

But before the project was completed, St. Louis filed an injunction to stop the project. The neighboring city realized that the river reversal would send all of Chicago’s waste downstream (formerly upstream) to them.

In 1899, after all the major digging had been done, St. Louis authorized its attorney to prepare a lawsuit, asking the U.S. Supreme Court for an injunction to stop the Sanitary District of Chicago from opening up the dams and letting the water go.

But a lawsuit can takes months to get ready. Chicago sped up construction to get the dams ready to open before St. Louis can get an injunction.

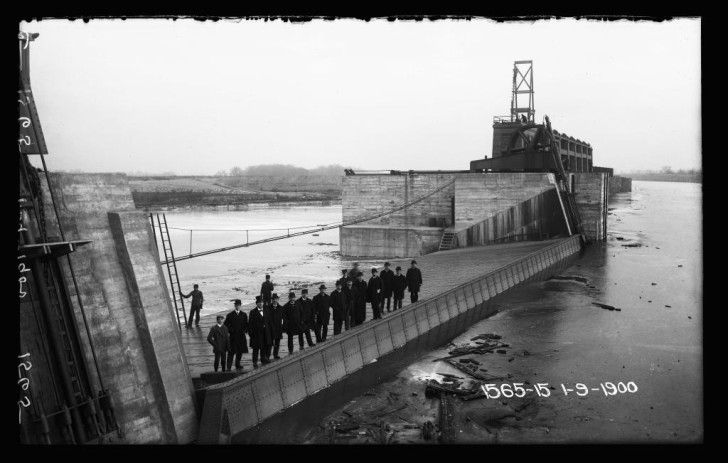

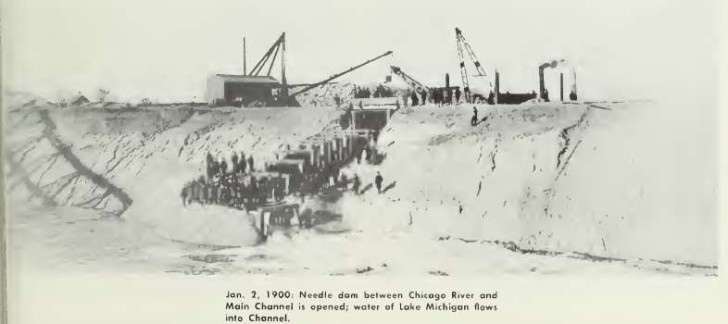

On January 2, 1900, the Sanitary District of Chicago trustees snuck out at dawn to meet on the city’s Southwest Side and dig open a cut that sent the river water flowing into the canal.

Two weeks later, on January 17, 1900, they take another early-morning trek, to lower a dam at Beaver Creek, releasing the water and sending it south towards the Mississippi

They turned the crank, posed for a picture in their fancy coats and top hats, then went out for a big lunch. While they were eating, they got word that St. Louis, had, indeed filed for an injunction that day. Too late. St. Louis pushed their case to the U.S. Supreme Court. They lost.

Now nothing could stop the water from flowing to the Mississippi. The story made the New York Times, with the headline, “The Water in the Chicago River Now Resembles Liquid.”

The canal and river reversal was later called a “Civil Engineering Monument of the Millennium” it was a functional monument to our dominion over the natural world. Or, so we thought.

Fast-forward a hundred years—to right about now—and the forces of nature are looking for another go-round. 19th-Century interventions in nature seem posed to boomerang back at us.

Reporter Dan Weissmann is a through-and-through Chicagoan. He spoke with journalist Richard Cahan, author of The Lost Panoramas: When Chicago Changed its River and Land Beyond.

Comments (7)

Share

I visited Chicago for the first time about a year ago and as an architect I noticed something very interesting going on with the ground plane. So interesting I decided to write my colleges about it on our firms blog. 99% clearly covered this better than I did … but I was happy to know that this was something interesting enough to make an episode about.

If you are at all interested, feel free to see my post HERE–> http://arcusa.com/node/228

What’s the name of the song played during the credits??

I was wondering the exact same thing. I eventually found it: If It Wasn’t For You (Instrumenta) by Handsome Boy Modeling School. Here’s a link: http://www.rhapsody.com/artist/handsome-boy-modeling-school/album/white-people-instrumentals/track/if-it-wasnt-for-you-instrumental.

Lake Street actually weighed 35,000 tons, not 35 (the weight of a mere 7 elephants). http://archives.chicagotribune.com/1860/04/02/page/1/article/the-great-building-raising

There’s a page now! https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ellis_S._Chesbrough

It is pretty short though. 99% is a source!

Yea i agree!!!!

There is an urban legend in Chicago that in 1885 an epidemic killed 60,000 people and that was why the construction of the canal was so fast. Did you see anything proving the legend