If you grew up watching Warner Brothers cartoons, you might remember seeing the name Chuck Jones in big letters in the opening credits. Chuck Jones directed cartoons like Looney Tunes from the 1930s until his death in 2002. He was also an animator, and brought the world characters like Elmer Fudd.

Chuck Jones was the creative force behind Bugs Bunny, and Daffy Duck, and Wile E. Coyote. But part of what makes his characters so memorable is the world that they inhabit. Part of what’s so striking about Looney Tunes is that they are recognizable as Looney Tunes even without characters in the foreground.

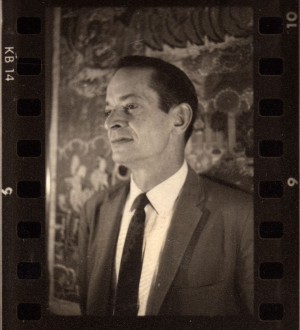

The backgrounds were revolutionized by one layout artist: Maurice Noble.

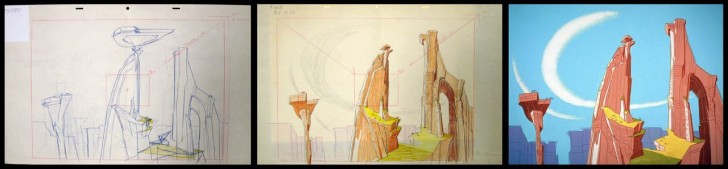

Layout artists create a painstaking works of art that allow viewers to instantly register where they are and what mood they’re supposed to feel—and then animators plop their drawings right on top of them. The dynamic is kind of like the straight man in a comedy duo—layout artists set up the gags, but it’s usually the animators who get the glory.

Layout artists are, both figuratively and literally, working in the background.

Even though Maurice Noble never drew characters, he was able to cultivate a distinctive style in his landscapes.

Maurice Noble spent most of his career working on cartoons, but he didn’t start out doing wacky stuff. As a young man, he wanted to be a fine artist, painting desert landscapes.

When he graduated from art school, Maurice got work at Walt Disney Studios. But he wasn’t there long. In 1941, Disney studios was torn apart by a strike. The artists wanted to create a union. Walt Disney took the walkout very personally. When it was over, he got rid of anyone associated with the strike—including Maurice Noble.

Noble wasn’t unemployed for long. When World War II broke out, he was drafted into a unit that made propaganda films featuring a cartoon character named Private Snafu. This crew was full of people from Warner Brothers, including Chuck Jones and Mel Blanc (who did the voice of Bugs Bunny, among many other characters). Noble found their style liberating.

After the war, Chuck Jones and Mel Blanc got Maurice a job working at Warner Brothers. And it was at Warner Brothers that Noble’s style began to develop.

The early Warner Brothers cartoons of the time—like Disney cartoons—had realistic, detailed, three-dimensional backgrounds. But Noble wanted to change that. He felt animation was a flat, stylized medium, and he wanted the backgrounds to support that aesthetic.

Noble pushed the cartoony-ness of the Warner Brothers backgrounds until they had the same sass as Bugs Bunny or the delusional insanity of Daffy Duck. In the Road Runner cartoons, The Coyote’s real antagonists are the desert landscape and the ACME corporation, which are conspiring to make his life miserable.

Eventually, Maurice started getting co-director credit on some of the films. But Chuck Jones was still reaping most of the acclaim, and their relationship suffered a rift in the 1960s while they were working at MGM.

Jones was working on an adaption of a children’s book called The Dot And The Line, but he was having trouble with it. MGM executives gave it to Noble, and under his direction, the film won an Academy Award.

But Chuck Jones still got director credit. In fact, Noble wasn’t even invited to the Oscars.

Jones and Noble had a falling out, though they did continue to work together. Noble may never have gotten the same recognition as Jones, though he did manage to have a lasting impact on the art of animation as a whole. Noble became a mentor to a group of young artists (known as “The Noble Boys”) who would go on to bring his approaches with them into the animation world today.

Reporter (and former Rugrats animator) Eric Molinsky met Maurice Noble once—they talked about Opera. Eric spoke with Bob McKinnon, who wrote a biography of Noble; Tod Polson, who is publishing the forthcoming book The Noble Approach: Art and Designs of Maurice Noble; and Scott Morse, a Noble Boy who now works at Pixar.

Extras:

- Our friend Sean Cole (of episodes #59 and #17) reported a really incredible Radiolab story about Mel Blanc—the voice of Bugs, Daffy, Porky, Private Snafu, and loads of other cartoon characters.

- As part of “Wagner Week” at WQXR, David Garland explored the use of “The Ride of the Valkyries” in film, and, of course, gave a shout-out to “What’s Opera, Doc?”

Comments (3)

Share

Great show about Maurice Noble and Warner Brothers. But there is someone else in the background of a lot of those cartoons also – and much of his music was used in the background of your podcast. How about an episode (or at least a shout out ) to Raymond Scott, who’s music was featured prominently in a lot of Warner Brothers cartoons. He did much more than this, however. It could be argued that he was one of the people responsible for creating what the “future” sounded like way back. But I digress…

Listening with eagerness much enjoyment. I am an old background painter and more significantly my father is Paul Julian. My father was a brilliant painter and he also loved to compose filthy limericks, many of which described Noble, Jones or their relationship. I brought my portfolio to Maurice once and he shredded my self-worth with cool, haughty pointedness………he was right.

Thanks for this. I’ve loved animation my entire life and I had never heard of Maurice Noble. After listening to this segment I immediately ordered the book on his art from Amazon