It’s hard to say where inspiration comes from. The path from the seed of an idea to its execution is often a long one. The brilliant architect Alvar Aalto expressed this sentiment well, in an extended metaphor about a fish in a stream:

“Architecture and its details are in some way all part of biology. Perhaps they are, for instance, like some big salmon or trout. They are not born fully grown; they are not even born in the sea or water where they normally live. They are born hundreds of miles away from their home grounds, where the rivers narrow to tiny streams. Just as it takes time for a speck of fish spawn to mature into a fully-grown fish, so we need time for everything that develops and crystallizes in our world of ideas.”

This is a story about such an idea, born hundreds of miles away in a far off stream. It is an idea that would travel from Northern Europe to Southern California, where it would take on a whole new life before making its way back again. It is a story in three acts.

Act One: California

It’s a shame that skateboarding is illegal is so many places, because skaters have a unique appreciation for architecture. They recognize the quality of concrete, the grain of wood, and the incline of a structure. They understand the way a landscape flows. Skateboarding is a way of reinterpreting the built environment, and imagining alternative uses for architecture. But it wasn’t always this way.

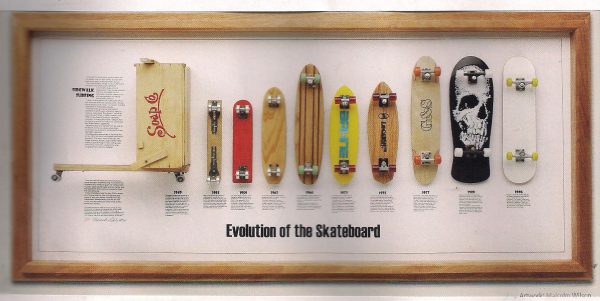

“The very first skateboard was called the skateboard scooter,” explains skateboarding pioneer and filmmaker Stacy Peralta. At some point, in the early 1960s (no one is quite sure when) someone just removed the handlebars of a scooter and rode the board like a surfer.

Skateboards were sold in toy stores and skateboarding briefly became a short-lived fad. Meanwhile, Stacy Peralta was a little surf rat growing up in Venice Beach, California. When the waves were bad in the middle of the day, Peralta and his friends went looking for a way to occupy their time — but what they really wanted to do was keep surfing. A friend’s brother had a few skateboards left over from the brief skateboard fad, so Peralta and his crew took to riding them.

Those early skateboards had hard, clunky wheels made out of clay, making it difficult (and dangerous) to ride them on anything but smooth, flat surfaces. Tricks at the time were correspondingly simple, things like standing up straight, balancing on the top of the board, or doing a little wheelie. Flatland tricks.

Peralta was really young, maybe seven years old, but he can remember skating for the first time. Even with those clunky clay wheels, Peralta found a blissful stillness he had difficulty articulating as a child. Right away, he realized he felt “more relaxed when I stand on a skateboard than when I walk.”

Since the fad had faded, Peralta and his friends struggled to find new skateboards in shops. Instead, they would hit up thrift stores and buy pairs of roller skates, which had clay, metal, or hard plastic wheels. They would cut the bases off of the skates, and put the wheels on planks of wood, then ride their creations back and forth all day long.

Then, in the early 1970s, an invention came along that would revolutionize skateboarding: the urethane wheel. These wheels were intended for roller skaters at the the dawn of the disco era, but a small company began producing them for skateboards. Kids in L.A. bought these wheels at surf shops (since there were no skate shops), and these new soft plastic wheels had more give to them — they had better grip and could roll over rougher terrain.

Urethane wheels opened up a whole new world of possibilities to skateboarders. Now they could skate on any kind of surface. Peralta, his friends, and the young skaters of Los Angeles began to hop fences and scope out buildings and parking garages, looking for new challenges in everyday built environments.

Then, in the mid-70s, there was a major drought in Southern California.

Couples were encouraged to shower together, and people were told not to water their lawns, or to fill up their swimming pools. And in Los Angeles, there were a lot of swimming pools.

The pools of southern California are very unique. They are curvy and free-form, shaped like peanuts and keyholes and kidney beans. They’re paved evenly throughout their rounded depths. As Stacy Peralta put it:

LA was the backyard pool mecca. And not just the backyard pool mecca, the properly beautifully designed backyard pool. I don’t know of anywhere else in the world that has that proliferation of that kind of voluptuous, sensuous design.

In the middle of the drought, suddenly, the pools of Los Angeles were all empty. They were the perfect places to skate. “They just were so beautifully conceived and designed,” says Peralta, “and we fell in love with the shapes.”

Peralta and his friends would hunt for pools, finding them at houses under construction and in fancy parts of town. They would climb fences and break into places. If there was a little bit of old dirty water in the pool, they would drain it out themselves with buckets or, eventually, with an industrial vacuum they would bring along. Then they would skate all over in the pool, cruising up and down the curved surfaces.

Riding in pools was a revelation to Peralta. When he could skate up a sloping wall, he got a feeling of weightlessness. It was extraordinary. “We were these scruffy kids and here we are riding in backyard pools and we know what we’re doing is beautiful. And we get to feel beautiful.” Skateboarding became a form of choreography, where skaters were trying to do as much as possible in the limited space of the pool, and look graceful while doing it.

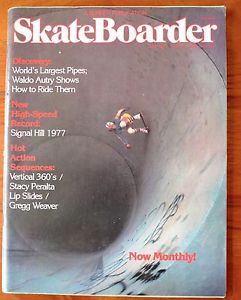

Back in the first wave of skateboarding in the 1960s, there had been a magazine called, simply, Skateboarder. It went out of business when the skateboarding fad died out, but in the 1970s, the magazine came back. And it featured Peralta and his friends, skating in these strange California pools. The magazine spread the word that skateboards were back, and they weren’t just kids’ toys anymore.

Back in the first wave of skateboarding in the 1960s, there had been a magazine called, simply, Skateboarder. It went out of business when the skateboarding fad died out, but in the 1970s, the magazine came back. And it featured Peralta and his friends, skating in these strange California pools. The magazine spread the word that skateboards were back, and they weren’t just kids’ toys anymore.

Eventually, Peralta and other skateboarders got so good at pool skating they were able to skate up over the edge of the pool and jump into the air. These aerial tricks led to another chapter for skateboarding, where extreme tricks took precedence. Think of the X-games, half-pipes, and Tony Hawk — all of which can be traced back to the rounded, biomorphic pools of Los Angeles.

Act Two: Sonoma

The curvy, kidney bean-shaped pools so beloved by California skaters can be traced back to one backyard in Sonoma County. And not just any yard — arguably the most famous private backyard in 20th century American history.

Justin Faggioli and Sandy Donnell are the owners and caretakers of the property known as the Donnell Garden, which is famous in the world of landscape architecture. It’s not the kind of thing the public can tour. It’s just a private residence: a modestly sized, retro-modern affair from around 1950 on a hill that belonged to Sandy Donnell’s parents.

The garden was planted in 1948. In the first half of the 20th century, traditional gardens were more or less plant museums, with symmetrical rows or sections of different kinds of flowers, maybe with the occasional geometric hedge or fruit tree.

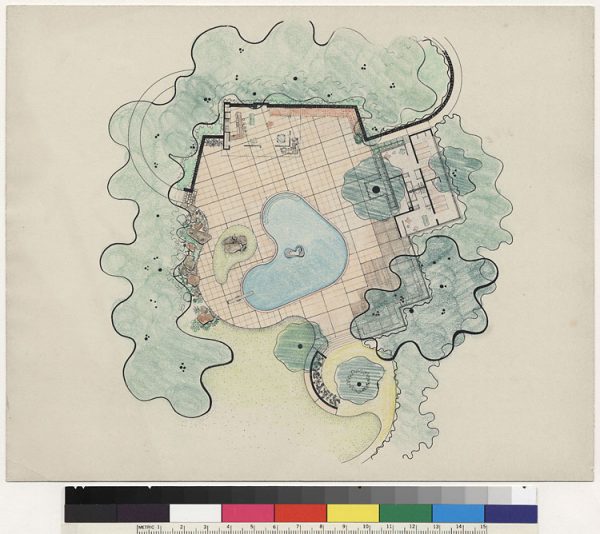

The Donnell Garden is nothing like a traditional garden. It’s mostly lawn. It’s a sea of cut grass, with tropical plant clusters and groups of rocks floating in it like ships or islands. And in the midst of it all sits a distinctively shaped swimming pool, believed to be the first of its kind in California.

It’s hard to overstate the importance of the Donnell Garden, to both formal garden designs and everyday American yards. Designed by landscape architect Thomas Church, it helped shape the idea of the modern backyard as we know, from its lawn and deck to its pool.

“I would guess, possibly with the exception of Versailles, that the Donnell Garden is probably the most published garden, at least in the 20th century,” says architectural historian Marc Treib.

Thomas Church was a firm believer that outdoor spaces could be designed for a wide variety of uses, rather than adhering to the traditional rows of flowers.

He believed that people could create whatever kind of space they wanted, which is why his 1955 book was called Gardens Are for People. Church thought yards could be like rooms of a house, able to serve real functions for owners who wanted to throw parties or simply relax and lounge in the sun or shade. And throughout the 1950s, lifestyle magazines like Sunset and House Beautiful featured the Donnell Garden on their covers. As Marc Treib puts it:

He believed that people could create whatever kind of space they wanted, which is why his 1955 book was called Gardens Are for People. Church thought yards could be like rooms of a house, able to serve real functions for owners who wanted to throw parties or simply relax and lounge in the sun or shade. And throughout the 1950s, lifestyle magazines like Sunset and House Beautiful featured the Donnell Garden on their covers. As Marc Treib puts it:

In many ways it became the icon, certainly of American modern landscape architecture. A lot of it being, of course, for the swimming pool.

Images of the Donnell Garden began to spread, and it became the epitome of the California outdoor lifestyle. Newly-minted suburbanites and landscape architects across Southern California began to imitate it.

It is impossible to know exactly where Thomas Church came up with the distinctive outline of this pool. In 1947, retro boomerang shapes were already appearing in everything from fine art to mass produced textiles and furniture. Church could have gotten the idea for the kidney-shaped pool anywhere. But there is a really interesting and widespread theory about where Church got his inspiration.

Act Three: Finland

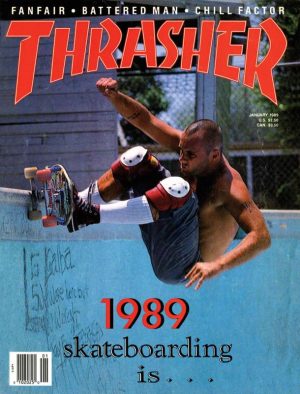

“Skateboarding came to my neighborhood at the end of the 1980s,” says Finnish skateboarder Janne Saario, in part thanks to magazines and videos featuring the California skate scene. “The first ones came when someone’s dad went to, you know, a business trip to the States, and then they brought back some videos.”

Saario, inspired by the California skate scene, went on to become a sponsored skater and competed in cities all over the world. Through skateboarding, Saario says, he fell in love with architecture and design, and went on to study architecture in University.

Saario, inspired by the California skate scene, went on to become a sponsored skater and competed in cities all over the world. Through skateboarding, Saario says, he fell in love with architecture and design, and went on to study architecture in University.

While in architecture school, Saario distinctly remembers a lecture he heard about the origins of the kidney pool. “There was a professor coming from California,” he recalls. “She was having a lecture. I saw her talking about The Donnell Garden. I think she was saying that it’s the mother of all kidney pools.” This struck him as a bit strange, since he know of another much older such pool, designed by Alvar Aalto.

“Alvar Aalto’s work and his life was exceptional in that sense in that he was a pioneer in cross-disciplinary thinking and design,” explains Antti Ahlava, architect and Vice President of Aalto University, which is named after Alvar Aalto.

Aalto is easily Finland’s most beloved architect. He designed public and government buildings all over Helsinki, and created Artek, a furniture company that is, to this day, successful all over the world.

Aalto is one of the most-studied architects of the 20th century. Frank Lloyd Wright loved Aalto — and he hated other architects. Frank Gehry also cites Aalto as one of the only other architects he admires. Aalto is an architect’s architect. And his work helped create a unique Finnish aesthetic, which was an important part of developing a unique Finnish identity.

Finland is relatively young. It only became independent in 1917. Before that, Finland was Russian, and it looks it. Helsinki has stood in for Moscow and Leningrad in a number of films. Its buildings are regal, intimidating, and very ornate. Finland wanted to step away from Soviet romanticism, especially because the rest of Europe was experimenting with a new architectural approach called Functionalism.

Functionalism was a reaction to the dirty, overpopulated, polluted cities of the 19th century, which were loaded down with extra trim and friezes and statues. “Functionalism wanted to be healthy. There was lots of sunlight, air between buildings. It was fresh,” says Antti Ahlava. Functionalism was like an architectural cleanse.

Aalto was tuned into what the Bauhaus was doing in Germany as well as the Modernist work of architects like Le Corbusier. But Aalto saw an opportunity to humanize and adapt Modernist impulses and make them more organic in terms of both form and material.

Aalto made curving partitions to break up the space. He used rounded tiles, and undulating counters — all crisp and functional, but a little more natural and cosy. While many Modernists toyed with sterile concrete and clean white paint, Aalto began to work with natural wood, bending, gluing and veneering it in novel ways.

So when an art collector and lumber heiress named Marie Gullischen asked Aalto to design her country home, the Villa Mairea, Aalto wanted to keep it very stark and clean, but also friendly and natural.

Of course, in rural Finland, if you’re going to have a villa, you need a sauna. And if you’re going to have a sauna, you need a pool to cool off in. So Aalto designed a pool with a very peculiar, rounded, curvy shape.

The story goes that Thomas Church, the California landscape architect who designed the Donnell Garden, went on a trip to Finland with his wife Betsy in 1937. Somehow they found out the address of Alvar Aalto’s home studio and got themselves there, and knocked on the door. Aalto welcomed them in and they grew to be friends. It’s quite possible that designs for the Villa Mairea (and its pool) were on display in Aalto’s studio while Church was visiting. Which might have inspired the pool in the Donnell Garden.

And then the Donnell Garden pool becomes famous, inspiring a slew of similar pool designs in California. And these other pools go on to be emptied out during the drought in the 70’s, inspiring a new chapter for skateboarding.

And that skate culture inspired kids around the world, like Finnish skateboarder Janne Saario, to take up skateboarding and architecture.

Janne Saario graduated architecture school, and developed a specialty. Today, he is the only skatepark designer in Finland. He designs curvaceous pools all over Europe — pools exclusively for skateboarders. He believes that public skate parks and pools should be a source of civic pride, especially in Finland, where, Janne likes to tease, modern skateboarding began.

I kind of use it as a joke, when we’re out with the skatepark builders – they’re usually from the States or Canada. And I try to claim skateboarding for having its roots in Finland.

Pool Parti

Some say that Alvar Aalto’s pool at the Villa Mairea was inspired by the soft bends in a Finnish lake. Or maybe Aalto was just excited about his ability to make wavy forms, a design tendency that would become his signature in his furniture and housewares. Or maybe Aalto was inspired by some other curvy pool somewhere else in the world that we don’t know about.

Aalto didn’t like to talk about his sources of inspiration. He didn’t write too much about them either, save for a small passage, an extended metaphor about his creative thought process, comparing it to a fish in a stream:

“Architecture and its details are in some way all part of biology. Perhaps they are, for instance, like some big salmon or trout. They are not born fully grown; they are not even born in the sea or water where they normally live. They are born hundreds of miles away from their home grounds, where the rivers narrow to tiny streams. Just as it takes time for a speck of fish spawn to mature into a fully-grown fish, so we need time for everything that develops and crystallizes in our world of ideas.”

Avery Trufelman spoke with John Nesci about Jolie Crider Memorial Skatepark in the Coda. Learn more about the project here.

Comments (9)

Share

Fantastic as always–but I was bummed to hear no mention at all of Frank Nasworthy, the dude that spotted Creative Urethanes’ material and first thought to try it on skateboards. He was the first to introduce urethane wheels to the southern California skate scene, and then his company, Cadillac Wheels, was the one first making and selling wheels to surf shops.

The episode had a lot to cover, but he was a key step in skating’s evolution and he often gets left out of the story. Full disclosure: he was a friend of my dad’s, but still.

Superb and inspiring episode!

I’d Love to hear you elaborating on some of the other tangents or threads you mention at the end.

RIP Jake Phelps.

THANK YOU, FOR THIS.

What is the connection between skateboarding and the new way of doing tracking shots in cinema? Does anyone know? Roman mentioned briefly at the end.

“Helsinki has stood in for Moscow and Leningrad in a number of films. Its buildings are regal, intimidating, and very ornate. Finland wanted to step away from Soviet Romanticism, especially because the rest of Europe was experimenting with a new architectural approach called Functionalism”. Seriously? Do you mean 19th century Russian classicism – the style seen on the Helsinki Senate square? Is this what you call “Soviet Romanticism” and oppose it to the Western functionalist? Have you ever heard of Soviet Constructivism, which was a part of international modern movement in the 1920s?

Guys, thank you for a very nice listening! I love the connection between skate and architecture, that’s my field. PS: the lady has an amazing voice!

Thanx for the great job you are doing!

Julie, Czech Republic

This episode is an aural Möbius strip of a narrative that is exquisite, with connections that are surprisingly organic and genuinely delightful.

The 2-years-after update is a second Möbius strip woven into the first one. The flow of ideas, the movement of thoughts, the joy of humanity, the thrill of architecture and the grandeur of skateboarding.

It’s poetic in its structure, surprising, but with echoes and turn backs and simply gorgeous, surprising and delightfully satisfying turns, and it turns back in itself. It brought me joy and made me sad. But it’s not sad, at all. It is joyous.

Fantastic episode! What was the song playing at 5:00??