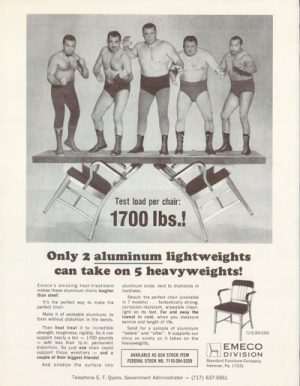

As the U.S. war effort ramped up in the early 1940s, the Navy put out a request for chair design submissions. They needed a chair that was fireproof, waterproof, lightweight and strong enough to survive a torpedo blast. In response, an engineer named Wilton C. Dinges designed a chair made out of aluminum, bent and welded to be super strong.

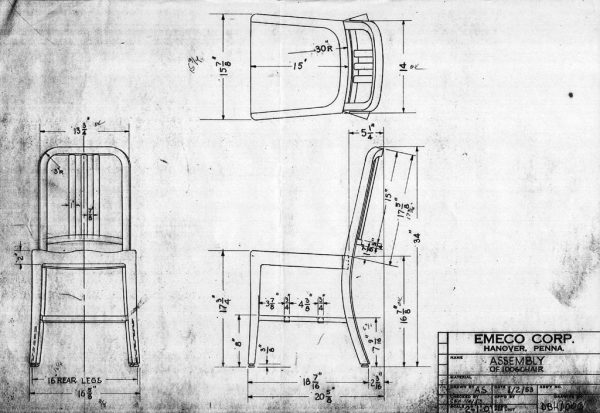

The chair was made to be relatively utilitarian, with an arched top and three slats coming down the back to meet a crossbar. A curved “butt divot” is one of its most distinctive elements.

To show off the durability of his creation, Dinges took it up to the eighth floor of a hotel in Chicago, where the Navy was examining submissions, and threw it out of the window. It bounced, but didn’t bend or break.

And so the Navy gave its inventor the contract, and he, in turn, opened a factory and called his new business the Electrical Machine and Equipment Company, or: Emeco.

Over the next few decades, Emeco built various other chairs but also shipped hundreds of thousands of the 10-06 Navy chairs to the US government from its factory in Hanover, Pennsylvania. These became standard issue for battleships, aircraft carriers and submarines.

In the 1970s, Emeco was purchased by a California businessman named Jay Buchbinder. But by the 1990s the company was losing a lot money, so his son Gregg took a trip to the factory to check on things. The situation looked bleak, recalls Gregg — “the guys were just waiting for the company to close.” Then he overheard a heated phone conversation between the office manager and a customer. After she hung up, he asked who she’d been talking to. “It’s some guy named Giorgio Armani,” she told him. Recognizing the name, Gregg started to dig through the files, and discovered Emeco was shipping chairs to designers like Terence Conran and hip entrepreneurs like Ian Schrager. Wealthy tastemakers had discovered the beauty of these indestructible Navy surplus chairs. Gregg suddenly realized Emeco could sell to a mostly untapped, higher-end market.

Gregg Buchbinder turned the company around,and today Emeco makes specialty chairs with architects and designers like Norman Foster, Frank Gehry and Philippe Starck.

The original 10-06, meanwhile, has become one of the most iconic chairs in the world, featuring prominently in films like The Dark Knight.

But not all of the chairs that bear this look are made by Emeco. A lot of them are knockoffs — fakes. Last month, Benjamen Walker of Theory of Everything walked 99% Invisible Host Roman Mars around New York city, pointing out real and fake Emeco chairs. Sometimes you can spot the difference in a design detail, or just the weight of the fakes, which are often heavier.

“In America today, most people think of design as shape,” Gregg Buchbinder told Walker on a tour of Emeco’s Harrisburg factory. “The average consumer doesn’t realize that design is so much more than that” — how the chair is made also matters. “There are 77 steps to produce the navy chair,” he explains.

Sheets of aluminum are used to mold the seat bottom (which, according to legend, was modeled after the derriere of Betty Grable, a famous Hollywood actress of the 1940s). Throughout the factory, skilled craftspeople can be found routing holes into extruded aluminum, and working with the three famous vertical back slats. The fact that these meet a crossbar and don’t go to the seat is an Emeco signature, as are three welds left unground at the top of the chair’s back (more welds used to show, but finicky design clients wanted them streamlined). Finally, the chairs go through a series of water baths and an oven, resulting in a chair that is, Gregg says, stronger than steel.

Many of the designers who work with Emeco want to see this 77-step process and make the trip out to meet the workers. Gregg recalls that “every time we take an architect or designer through this whole process, they always say the same thing: you need to charge more for your chairs.” But architects must have a big chair budget, because these chairs are not inexpensive: a new 10-06 costs around $550.

Meanwhile, though, “there are several websites that have listings from vendors of counterfeit chairs,” says Madson Buchbinder, Gregg’s wife, who does press for the company and often looks for knockoffs. She scans platforms like Houzz, eBay, Amazon and Alibaba, and notes the exact copies are the easiest to get taken down — when there is no ambiguity, marketplaces are quick to comply. And in 2012, when Restoration Hardware started selling a “Naval Chair,” they settled out of court. Emeco has also gotten Target and IKEA to take down fakes.

This strategy works because Emeco has “trade dress protection,” which is designed to protect consumers from the lookalike imitations of name-brand products. It doesn’t protect the function or process, but rather the look, which, in this case, means the iconic shape of the chair.

But not everyone thinks Emeco deserves this protection. Lawyer and author of The Knockoff Economy: How Imitation Sparks Innovation Christopher Sprigman is a skeptic. He notes that when people see this iconic chair, they don’t think “Emeco,” they think “nice chair.” He also doesn’t believe it’s particularly distinctive and that in a full-out legal battle Emeco might lose their trade dress protection in court.

What bothers him is that companies like Emeco and Herman Miller and Vitra turn to the law to take knockoffs out of the marketplace, because “to the extent this succeeds, these designs become the territory of the rich and no-one else can access them.” In short: he believes these protections are bad, not good, for consumers. “One of the things that is real about them [is] they’re for the rest of us … they bring the rest of us into the world of the artist … they allow us to participate in the fashion world, even if we can’t afford the stuff on the runway … they allow us to participate … [and] that’s democratizing.”

But for Gregg, Emeco knock-offs also make the country (and the whole planet) worse by filling landfills with garbage chairs. “All of our product is engineered for the longest life possible,” he says. His “goal is to produce something where it has the least impact environmentally and has the longest life … the opposite of planned obsolescence.”

In some cases, the knockoffs are arguably sufficiently different to be their own thing, but in many cases the copying also goes over the top. Take, for example, the Delta Chair from Crate & Barrel, which adds a fourth slat to the Emeco design, but also leaves selective unground welds, imitating a small key signature detail. The design of the Delta Chair may be different enough to avoid trade dress lawsuits, but Gregg says it intentionally tries to copy the essence of Emeco’s Navy Chair.

He also notes that despite all of these similarities, there’s a key difference: this chair can’t survive a fall from an eight-story building.

Comments (18)

Share

“…if you wanna be stylish and have a house that nice and you don’t have a ton of money you may buy a knock-off chairs”

What kind of argument is that? Maybe then we should allow to buy and sell knock-off Rolex or Lamborghini? No. Design is one of the parts of intellectual property of object and should be protected by law.

Don’t have the money? Don’t buy that chair. There are plenty other stylish and affordable designs in the world.

I love 99Percent, but I’m calling “Foul!” on this episode for the sole reason that the chair-toss was a cheap tease that lazily evades an essential difference between science and engineering — the latter being the chief domain of designers.

Manufacturers thrive on anecdote and untested claims, just like Wilton Dignes eight-floor toss. Unless you subject other products to the exact same test, not to mention document the methods and results and submit them to public scrutiny, then you have only an unchallenged anecdote that lives on as myth.

Roman was journalistically irresponsible not to follow through on that test. True, 99Percent isn’t investigative journalism by any stretch. But it also shouldn’t become complicit in perpetuating anecdotal myths when they might be easily and conveniently challenged.

Really, Roman, it was a cop-out to hide behind liability and not follow through tossing the Crate & Barrel knock-off. It only suggests you’re afraid the result might show the Navy chair to be really quite ordinary. And while we’re on the topic, just where’s the paperwork showing the results of those torpedo tests?

I have an authentic Eames chair I’ve been trying to sell, but potential buyers keep trying to talk me down in price by telling me it’s a fake. It’s really maddening, especially when they can point to YouTube videos about spotting fakes made by wannabe furniture experts who have no idea what they’re talking about.

Open source furniture is the way forward!

http://www.opendesk.cc

Boy, that was a tough one that surprisingly got my hackles up. As a designer and creator who has had intellectual property stolen, it is frustrating to hear someone defend a knockoff. Knockoffs aren’t altruistic – they are absolutely opportunistic. It entails riding a trend or design or idea for personal gain, not somehow delivering an iconic design to the masses. It is not for the societal good; it is capitalistic as hell.

How about this: I’ll write a book called The Knockoff-Knockoff Economy: How Imitation Sparks Aggravation. I hope it doesn’t affect Sprigman’s bottom line, but why should I care if it puts a little extra coin in my pocket at his expense? If he really wanted this information out there for everyone’s benefit, then he would have published it for free (like 99PI). It’s fair game then, right?

If a person wishes to be altruistic and allow their work to be copied and/or improved upon, they leave it open-source. Adam Savage does this a lot (he can afford to do so). However, if a person wishes to retain that information, even if for personal gain, that wish should be observed for it’s lawful term. Granted, I think protections should expire after a reasonable period, but respect each other’s work – Theft is theft.

We are all inspired by others. If a particular design inspires a new direction, fantastic – that’s innovation. I am inspired all the time, and you should be, too. However, if you make modifications and call it yours, you are stealing (or plagiarizing, infringing, faking, counterfeiting…). It is, to me, the same as Vanilla Ice calling the beat for “Ice Ice Baby” his original, when it is clearly Bowie & Queen’s “Under Pressure”. Was it innovative? It’s arguable. They settled out of court. Give credit where it’s due or get your own ideas, would ya?

I love you, 99PI – keep up the good work. Especially because, it makes me think!

To counter those design lovers above, I think it was great to have some perspective from the pro knock off crowd. The claim of 70 years after death of the creator is an absurd length of time for the monopoly of gains from these types of products. While as a staunch capitalist I see the value in property rights, the argument that “mine will last longer” is something the market can and does appropriately value. Using the law to shut down any competition for potentially 150 years is insane. If you want to regulate waste, then regulate waste. Stopping production in the first place is not the solution.

Knockoffs aren’t altruistic, they are regular people trying to apply open market principles on unnatural monopolies provided by a government. While rewarding creators for their creations has value, the protection supposedly provided to designs like this is far too extensive, and limits progress as a society in the exact method as described on the show, by restricting availability solely to the rich.

The point of the legal framework is to benefit society by meeting the need of creators for remuneration (and thus chosing to create in the first place). If the creations aren’t actually available to society due to absurd price demands, what’s the point of protection? If you don’t want regular people to have access to your creations, why not just live as a personally sponsored creator by a rich person or corporation who can keep it all as trade secrets?

Is nobody bothered by the fact that these jerks probably jacked up the prices on their aluminum chairs by 10x because Italian designers were buying them? Aluminum is one of the cheapest materials you can make something out of and they’re marketing it like it’s the second coming of Jesus. This chair is probably worth 50 bucks, which is why the knockoffs cost about that much. 550 dollars for a freaking aluminum chair is nonsense. Nobody should pay that price for this.

Hearing this story reminded me of Kotobuki, a Japanese company that produces not only chairs (since it’s founding in 1914), but also capsule hotel modules, which I toured a couple months ago for work related reasons.

Would love to hear a story on capsule hotels!!!

https://www.kotobuki-seating.co.jp/en/company/history.html

The chair in the Dark Knight clip appears to be a knock-off as well! A good view of its four slats flashes briefly at the 4:00 mark.

Good eye! It’s authentic, but it’s a variant design with added cushions and slightly different details like that.

(Copying from my comment on Reddit)…

I was really interested in this podcast as I have a couple of these chairs…kind of. I have 2 chairs that were salvaged from a major manufacturing company (taken out of the smoking room in the 80’s). They were incredibly filthy with nicotene and other stains of which I won’t speak, but cleaned up beautifully. I knew the design was for the Navy, but wasn’t familiar with Emeco….just keep them around because they’re cool. However, they’re not Emeco chairs – they’re Goodform chairs manufactured by General Fireproofing, which I always assumed was a knock-off..looks like they were manufactured in 1954. However, the podcast episode got me wondering again and I started looking into things again….

So here’s the plot twist – I saw a couple of chairs listed on Ebay with the note that “Originally designed at the request of the US Navy to be used on Navy ships and submarines, General Fireproofing Company began manufacturing these chairs in 1936. The GoodForm chairs have since become one of the most recognizable products of the 1930s and 1940’s, and their aluminum chair design was eventually used by the Emeco company as well, who still continue to manufacture chairs today in this design. ”

So, it sounds like maybe Dinges of Emeco really didn’t design these originally?? Now I’m very curious.

Concerned about pricing out of reach of the lower classes? Buy it used.

There is no used market if nobody wants to sell theirs.

Should have called the episode “77 Steps – Benjamen Walker is in this one” so I would not have waited almost two weeks to listen to it.

Just spotted a knockoff Crate and Barrel “delta chair” in season 2 episode 10. St about the 3 minute mark.

Of West World on HBO

Great episode and I think that its funny that people take so much offense at people copying chairs. I can’t imagine a carpenter in the 1700s taking someone to court for “copying the design of their chair”. This is what happens when designers care more about making money then making a more comfortable and efficient world. Also a couple typos in the first paragraph you say “In response, engineer named Wilton C. Dinges” it should say “In response, an engineer named Wilton C. Dinges”. Also you say “Some argued the the design should be protected” when it should say “Some argued the design should be protected” only one the.

Great episode! The Eameses were aware that knock-offs existed during their lifetime and would continue to be made after their deaths, but they did not approve of them. In 1960, the Eames Office made a poster that said “Beware of Imitations — Enjoy the comfort of the REAL THING designed by Charles Eames for Herman Miller Inc. These are the ORIGINALS! Accept no substitutes.”