Information technology is arguably as old as the written word, but the 1900s saw the rise of a paradigm-shifting design all too easily taken for granted. The ancients had clay and stone marble tablets; offices in the industrial revolution had desks with drawers and cubbies and folders for loose papers; and the 20th century had filing cabinets, humble in appearance yet essential to a paradigm shift in information storage.

In his book The Filing Cabinet: A Vertical History of Information, author Craig Robertson explores the evolution of filing cabinets not just as designed objects but also as symbols imbued with meaning and associations that have shifted dramatically over time. For contrast, first imagine a world before filing cabinets; clerks and secretaries keeping track of information in ledgers, bound stacks, or desktop slots. “The shift from bound volumes to filing systems is a milestone in the history of classification; the contemporaneous shift to vertical filing cabinets is a milestone in the history of storage,” writes Robertson.

The design is so simple, pragmatic, and generic (at least in hindsight), it may not come as a surprise that historians are unsure precisely who invented the first filing cabinet as such. Usually stacked four drawers high, these functionalist units easily fade into the backgrounds of offices, at least now that they have become commonplace as both storage units as well as room dividers.

The design is so simple, pragmatic, and generic (at least in hindsight), it may not come as a surprise that historians are unsure precisely who invented the first filing cabinet as such. Usually stacked four drawers high, these functionalist units easily fade into the backgrounds of offices, at least now that they have become commonplace as both storage units as well as room dividers.

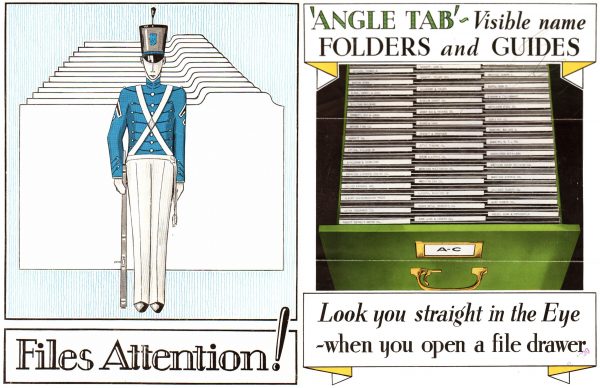

Folders and tabs were critical, but perhaps the most significant (if obvious) feature of these units was simply that they turned pages upright; stored vertically, papers could be sorted into folders for easy retrieval from above. Organized into files using labels and text, cabinets could accommodate a variety of paper sizes (particularly in the decades prior to standardization) as well as non-paper artifacts. It was nothing short of a revolution in terms of saving and referencing data. Some context and nuance was arguably lost in this shift to standardization, ushering in an era more focused on rote information than complex knowledge.

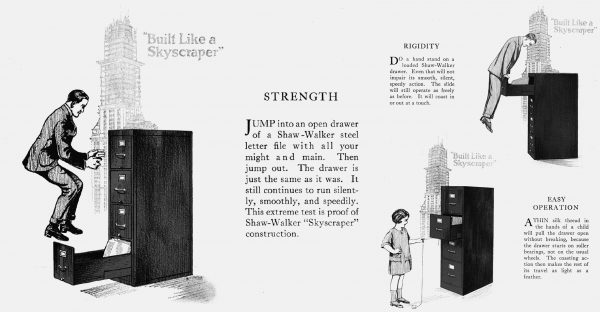

Other factors playing into the success of this new office technology included the proliferation of steel filing cabinets; these were durable — resistant to damage, bugs, the elements — as well as strong, able to carry up to 100 pounds per drawer without buckling under the weight. Such rigid vertical storage units were also naturally compared with other impressive steel creations of the Modern era: skyscrapers.

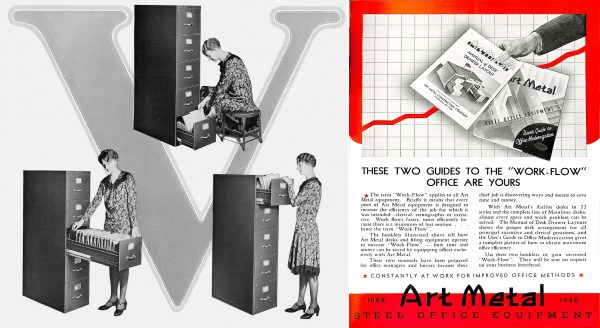

Culturally, argues Robertson, the filing cabinet also played a role in establishing and reinforcing gender roles in an age of work increasingly centered around offices. As seen in period advertisements, “female file clerks were expected to handle papers, but not to understand their contents; in contrast, it was male managers and executives who read the files, performing jobs that purportedly required thought.” They thus reinforced an implicit divide, coding the idea that knowledge was still the domain of men while information could be handled by women. This, says Robertson, arguably helped relieve male anxiety about women in the workplace, relegating female colleagues to supposedly rote roles and diminishing the status of this oft overlooked form of labor.

As the 20th century unfolded, filing cabinets became increasingly loaded, both literally (with tons of paper) but also with additional meaning. What started out as a symbol of modernity and efficiency became bogged down with associations like information overload and governmental bureaucracy — endless aisles heavy with paperwork. In popular media portrayals, filing cabinets have been used to show that a character is well or poorly organized, or more recently: that an older office space is out of touch with modern information technologies.

Looking back, Robertson suggests that “the file cabinet must be perceived as a distinctly 20th-century technology — as a response to a particular moment in the evolution of capitalism, when the volume of information dramatically increased and when that information was recorded, stored, and circulated primarily on paper.” And in some ways, its legacy has persisted in the computer age, for better and worse; file folders are still used to sort our information digitally. And much like messy filing cabinets, things still get lost in the shuffle, arguably compounded by our ability to store so many files in binary form. The ability to store more data inevitably leads to storing more data. For more, check out Robertson’s book: The Filing Cabinet.

Comments (2)

Share

It took me a while to spot the pun in the title. Nice one!

This pic from my postcard collection says it all!

https://flic.kr/p/2mdqpaa