Soccer came to Brazil in the late 19th century. It was first a game of the elites but then over time became a game of the poor and working class. In this sense, says BBC journalist Fernando Duarte, soccer was the country’s true revolution.

And if soccer is Brazil’s revolution, the Brazilian soccer shirt is its flag.

The Brazilian soccer shirt is iconic. Its bright canary yellow with green trim, worn with blue shorts, is known worldwide. Compared with other soccer jerseys, the uniform is joyful and bold and seems to capture something essential about Brazil.

But it was not always this way. Brazil used to play in plain, unremarkable white shirts. The story of how the uniform changed goes back to the World Cup of 1950, held that year in Brazil for the first time.

David Goldblatt, soccer writer and historian, sees the 1950 World Cup as a transforming event in the world’s perception of Brazil — from a view of the country as an agricultural plantation economy to a new, urban industrialized power in the world.

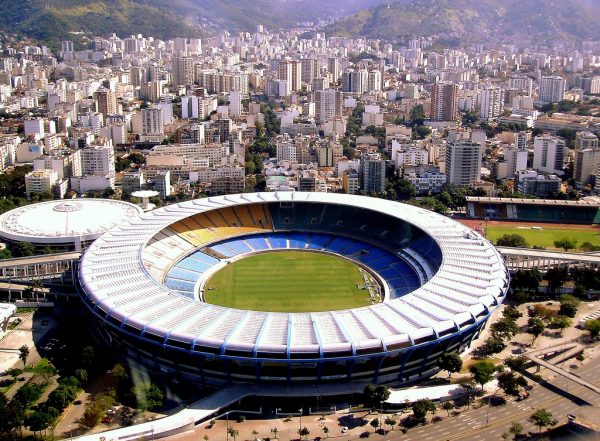

The soccer stadium built for the World Cup in Rio de Janeiro (the Maracanã), symbolized this transformation. It was like a stadium from outer space, a fabulous, flat white concrete oval with flying buttresses. The stadium looked like a huge flying saucer dropped into the center of the city.

A lot of optimism about the country and its future surrounded the World Cup that year, and it made the expectations of success for the Brazilian soccer team extremely high. As the tournament began, they did not disappoint — beating Sweden, then Spain, then Mexico and Yugoslavia. The final game would be with Uruguay, and because of the tournament’s structure, Brazil only had to tie the game to win the World Cup.

Historically, Uruguay had been a strong team, but they were now a waning power. The former Brazilian province was now playing as the underdog and its captain used this status to urge his players on.

On the day of the World Cup final, all of Rio was focused on the game, and a good fraction of the city was actually there. Some estimates for the final game put the crowd in the Maracanã at more than 250,000 screaming fans. As players emerged they were hit with a wall of noise.

In the first half of the game, Brazil failed to get a goal and the crowd grew nervous. Then, Brazil scored and there was a giant sigh of relief from the crowd. Even the journalists ran onto the field and embraced the players. It seemed like the game was won for Brazil.

But halfway through the second half, Uruguay scored, tying the game. Everything would have been fine for the team had Brazil been able to hold at a tie. But then came the turning point. Uruguayan winger Alcides Ghiggia dribbled down the right side looking to pass. Anticipating his pass, the goalkeeper moved out of position. Ghiggia noticed this and instead of passing he shot and scored. There was utter silence from the Brazilian crowd.

Alcides Ghiggia once said that there were only three people who silenced the crowd at the Maracanã – Frank Sinatra, Pope John Paul II, and himself.

Brazil lost that game, and Brazilians were absolutely crushed. People left the stadium in tears, and some of their tears transformed into racist grudges. Recriminations came in quickly, and many focused on the goalkeeper, Barbosa, who was black. Barbosa and two other black players become the scapegoats. Later in life, Barbosa told the story of hearing a woman whispering to a child, “this is the man who made Brazil cry.” It was more than 50 years before the Brazilian team picked another black goalkeeper.

But Barbosa wasn’t the only focus for blame. Everything was scrutinized, including those plain white jerseys the players had worn in the game. Brazilians thought they were cursed and the soccer authorities decided to hold a competition to design a new uniform.

The contest had one key stipulation: the colors of the uniform had to include all the colors of the Brazilian flag (green, blue, yellow, and white). Hundreds of people entered the contest including Aldyr Garcia Schlee, a nineteen year-old illustrator from a small town on the border between Brazil and Uruguay.

Working four colors into just the shirt would be difficult, but Schlee soon realized that he could use the whole uniform to incorporate the colors of the national flag. The result was a uniform of blue shorts, white socks, and a yellow shirt with green trim around the neck and sleeves. This design won and went on to become an iconic symbol of Brazil, full of sun and life.

In 1962, the Brazilians won the World Cup in Chile in Schlee’s uniform. Players like Pele wore the yellow shirt and dazzled the world with their extraordinary skill and beauty. After color T.V. arrived, the world watched Brazil in their shimmering yellow shirts win the 1970 World Cup in Mexico.

Aldyr Garcia Schlee had created a national symbol which was as visible and loved as the country’s flag itself.

But reality wasn’t living up to the image of Brazil that Schlee had created. Schlee had gone on to establish an academic career, but in 1964, a brutal U.S. backed military dictatorship took power in a coup. Schlee, among many others, was considered subversive and arrested. He suffered mental and physical torture, and when released lost his teaching job and was banned from leaving the country.

The dictatorship lasted twenty years. But despite the difficulties of living under the watchful eye of the military police, Schlee became a successful writer and academic. In novels, short stories and his academic work, his specialty became life on the border between Brazil and Uruguay.

Schlee was born in Brazil, but less than a mile from the border with Uruguay. Growing up in this border town as well as his experiences under military rule, shaped his feeling about Brazilian nationalism and made him wary of patriotism. Schlee envisioned a better world “without limits or borders.”

Of course, the soccer fan in Schlee can’t help but be proud of the Brazilian team. But Schlee has a secret, or at least something he never shared with those who knew he was the designer of the famous yellow shirt back in the day. Schlee roots for Uruguay.

These days when Brazil plays Uruguay, Schlee, like other soccer fans, suits up in his favorite jersey — but not the yellow one that he designed — a sky-blue one, the color used by Uruguay’s team. Then he crosses the border and finds a quiet bar to watch the game.

Comments (8)

Share

Hate to be that guy, but the sound bite you use with “Gooooooal” is actually in Spanish, from a Spanish radio station.

We re-edited the piece to address this (should be updated if you download it again).

I have to say, when I saw the title for this episode, I thought it was going to be about the Garden State and not about football uniforms. Alas, no love for New Jersey.

Same. It was interesting, but not as much as our beloved state.

Great story, unknown even for us brazilians. The yellow jersey is so iconic we take for granted that she always existed, like the sun ;)

I’m a Brazilian living in the UK and one of the first cultural shocks I experienced when arrived here the the ‘lack of enthusiasm’ by the football narrators on TV when a goal was scored. It’s so bizarre to us that lots of us living here watch the match on TV on mute with the audio of any Brazilian online radio simultaneously.

And yes, the shirt has this powerful connection with our country identity. Whenever we need to show support, not necessarily sports related, we just put the shirt on. This is happening a lot recently due to the current political troubles going on there.

Given the karmic alignment of the stars and the beautiful gesture of the team, I’d love to hear you rerun this episode

Aldyr Schlee, designer of Brazil’s famous yellow jersey, dies http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-latin-america-46243922

Seems like the craze over the colours of a football jersey has been reignited in Germany!

http://www.whoateallthepies.tv/kits/280064/we-will-only-use-our-traditional-colours-bayern-munich-vow-to-have-simple-red-and-white-shirts-for-rest-of-eternity-after-bowing-to-ultras-complaints-over-blue-trim.html